Political shifts in Brazil have revived international optimism, yet across South America, forest loss is accelerating. As COP30 approaches, experts warn that pledges alone will not save the rainforest

By

The election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as president of Brazil in 2023 gave climate advocates a huge boost. Replacing Jair Bolsonaro, the ‘Trump of the Tropics’, under whose watch the annual rate of deforestation in the Amazon surged nearly 60 per cent, Lula made it clear that he intended to improve the health not just of the rainforest but of those who lived there.

And, in Brazil at least, there has been progress. Deforestation has dropped 50 per cent compared with 2022 (the final year of the Bolsonaro administration). Lula’s administration revived Brazil’s Amazon Fund, unlocking more than a billion US dollars in international finance to support conservation.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

‘Lula’s first year did bring results; deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell, showing that political will and stronger enforcement still matter,’ says Butler. ‘He has restored international credibility to Brazil’s climate diplomacy and bought some breathing space for the Amazon.’

The key drivers of deforestation remain ever- present, according to Ana Clis Ferreira, Zero Deforestation spokesperson for Greenpeace Brazil. ‘In the Brazilian Amazon, agribusiness – especially the conversion of forests for the expansion of livestock, palm oil and soybean cultivation [used for animal feed for beef, sheep and chickens] – continues to be the main destination for newly deforested areas,’ she says. In all,

80 per cent of global deforestation has historically been a direct result of agricultural production. In 2024, however, a new factor intensified: for the first time, fire was the main cause, accounting for nearly half of all forest lost. The UNFCCC has warned that we are approaching a tipping threshold: lose 20–25 per cent of the Amazon forest and vast areas could simply deteriorate into savannah. Brazilian scientists calculate the current figure is 17–18 per cent loss, with parts of the southern Amazon showing signs of permanent drying.

The impacts have long been established, says Ferreira: ‘It compromises local biodiversity, threatening both emblematic fauna species such as ocelots, jaguars, giant otters, monkeys and endemic birds, as well as plant species crucial to ecological regulation, nutrient cycling and ecosystem resilience in the face of climate change and human pressures.’

The fate of the Amazon is not just a national concern but a global one. As the largest rainforest on Earth, it stores vast amounts of carbon and drives rainfall patterns far beyond South America. Its loss would reverberate through global food systems and climate stability.

Like the data on rainforest loss, Lula’s record is ambivalent, for he has become mired in realpolitik. His government is exploring offshore oil reserves along the country’s Equatorial Margin – an area of hundreds of kilometres of coastal water running up to the border with French Guiana. ‘We want the oil because it will still be around for a long time,’ he said last January. ‘We need to use it to fund our energy transition.’

Meanwhile, Brazil’s main environmental regulator has been criticised by Lula for delaying the issuing of drilling licences to oil giants such as Chevron, and in August, he gave presidential approval for a bill that streamlines such applications – in theory, fast-tracking them (although

he did also veto 63 amendments in order to address environmentalists’ concerns).

‘Lula was never going to be a silver bullet for the Amazon,’ says Butler. ‘His return to office was greeted with relief, if only because the bar set by Bolsonaro was subterranean. That tension – champion of conservation abroad, pragmatist at home – is real.

Every policy must be bartered, and environmental ambition is often traded away for survival.’ Ferreira recognises this tension too: ‘Lula was elected as a coalition government, which sought to reconcile views, so we cannot close our eyes to ambivalence. Our National Congress is strongly influenced by the right, political conservatism and anti-environmentalism.’

Deforestation confounds the environmental movement. Never before have forests been so high up the political and social agenda; never have rainforests enjoyed so much protection, been monitored in such detail by satellite, or civil society been so mobilised to support them. Sunlight, the cliché goes, is the best inspector. Why then are rates of forest loss still soaring? Can the COP30 delegates put the world back on track to meet the pledge of its Glasgow predecessor in 2021 to halt deforestation by 2030?

‘To meet that goal would require annual reductions of 20 per cent, starting yesterday,’ says Butler. ‘What needs to happen is not mysterious. The pledges exist; what is missing is scale and speed. We have had three decades of COPs, heavy on rhetoric and light on enforcement. Even when agreements are signed, national politics often blunt their impact. The United States has never ratified a global climate treaty.’

The real momentum, he argues, lies elsewhere. ‘Progress has come through national courts ordering governments to act, Indigenous peoples securing

land rights, corporations being forced to clean up supply chains, and financiers tightening lending criteria. Consumers have leverage too. These forces are reshaping the landscape more tangibly than many of the communiqués from UN halls.’

Greater efforts to scale up recognition of Indigenous and local community lands are also essential, adds Joe Eisen, executive director of Rainforest Foundation UK, who argues there is a clear link between recognising the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities and better environmental outcomes. ‘These come at a fraction of the cost of conventional protected areas,’ he says. ‘In Brazil, there are very clear differences in the rates of deforestation inside and outside of titled Indigenous lands.’

Ferreira believes the symbolism of a COP in the Amazon should galvanise meaningful action in Belém. ‘It’s a unique opportunity for Brazil to reaffirm its leadership in climate negotiations, place the forest at the centre of global attention and encourage concrete actions to protect it,’ she says. The need for change, she warns, is acute.

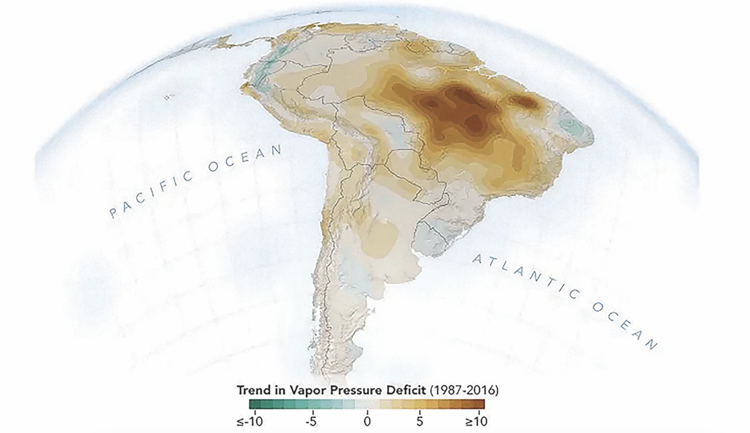

Vapour pressure deficit measures the difference between the maximum amount of water vapour the air can hold and the amount of water vapour present. The bigger the deficit, the more prone the region is to fires. The darkest zones show the areas with the largest deficit. Image: Shutterstock

‘Although the window for action to curb the climate crisis is rapidly narrowing, measures can still be taken,’ she says, including directing financing to Indigenous peoples and local communities, strengthening their capacity to protect and restore critical ecosystems, and stopping the flow of resources that finance activities and companies that contribute to the destruction of biomes. ‘Despite these challenges, I am cautiously optimistic,’ she adds.

The sense of sand slipping through an hourglass is also felt by Butler. ‘We are not yet past the point of no return, but we are running out of “later”. Forests are resilient – left alone, they regenerate – but only up to a point,’ he says.

For many, COP30 will be judged not on speeches but on whether it produces mechanisms to fund protection at scale and hold individual governments accountable for promises too often broken.