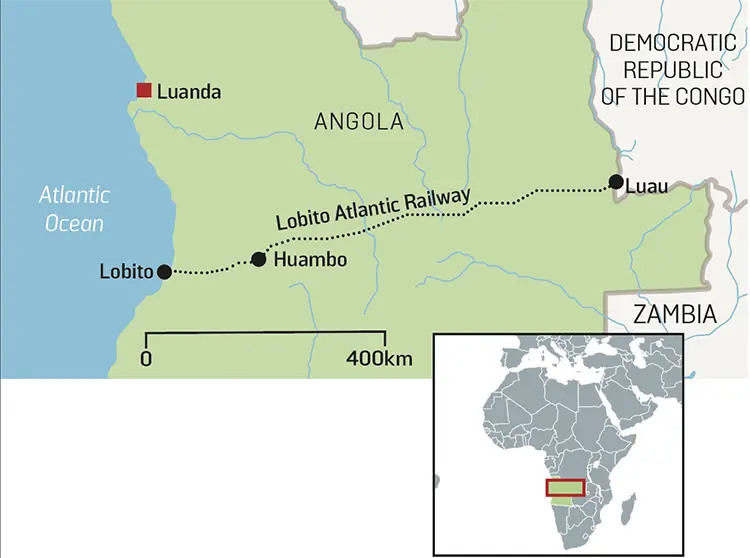

Stretching from Angola’s Atlantic coast to central Africa, the Lobito Corridor is now a key rail route in the global scramble for critical minerals — and a test of whether the West can match China’s reach on the continent

Words and photographs by

At the train station in Luau, a dusty border town between Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), waiting passengers jostle anxiously for space on the platform as brooding storm clouds build overhead. Some have been waiting for hours. The train before them has only two small carriages and there are several hundred passengers. Those who don’t get a spot on board could be waiting days for the next train. Police and railway officials do their best to control the boarding process, but as the storm breaks and fat, warm droplets of rain begin to fall, all semblance of order vanishes.

The crowd surges towards the train, clutching tightly onto their luggage as they fight their way to the doors. The few seats are quickly taken, after which the passengers begin to claim every inch of available standing space. A boy of about six is shoved into the carriage headlong through an impossibly small window, to be helped down by strangers on the inside. Mothers change babies’ nappies on their laps. Chickens squawk in the chaos as vendors selling snacks and drinks weave their way through the tangle of bodies. The heat is stifling.

This is the Lobito Atlantic Railway, and though it might not seem like it, this historic yet beleaguered train line has become a major new frontline in the global scramble for the critical minerals that will fuel the world’s green energy transition. Stretching more than 1,300 kilometres across Angola and carrying both passengers and freight, the railway connects the Atlantic port of Lobito with the central African Copperbelt in the DRC and Zambia.

For the past decade, it has been run at a fraction of its true capacity by a Chinese company. Now, a US-backed consortium has taken over, promising to invest vast sums to improve the line in what analysts see as the USA’s biggest challenge yet to China’s growing influence in Africa and its dominance of the continent’s critical minerals. If it succeeds, the project’s backers say, the so-called Lobito Corridor could not only vastly facilitate the passage of cobalt and copper, among other minerals, to the West, but also transform the lives of ordinary Angolans and provide a new blueprint for Western investment in Africa.

‘It’s going to set a standard for the rest of the world,’ said US President Joe Biden during a visit to Lobito in December 2024 – the first by a US president to Africa in nearly a decade. ‘We’re at one of those transition points in world history where what we do in the next several years is going to affect what the next six, seven, eight decades looks like – and I think this is one of those milestones.’

Yet not everyone is convinced. Critics say the move has come a decade too late, with most of the continent’s critical mineral reserves already tied up by China. At the same time, the Swiss company at the heart of the project has been embroiled in a string of corruption scandals, including in Angola. And some question how much of the project’s multi-billion-dollar price tag will trickle down to the impoverished communities living along the corridor.

Initiated at the turn of the 20th century, the railway was once the largest employer in Angola, transporting millions of tonnes of cargo per year from the interior of Africa for export overseas. But during the country’s brutal, decades-long civil war – fuelled in large part by rival Cold War superpowers – it fell into disrepair. By the time peace was eventually declared in 2002, the route was littered with tens of thousands of landmines, with just 34 kilometres of track still in operation.

After the war, the railway was restored by a state-owned Chinese firm in a US$2 billion infrastructure-for-oil deal. When it was finally re-inaugurated in 2015, grand promises were made. The line would soon be carrying as much as 20 million tonnes of cargo a year, the company said, and some four million passengers. Yet a decade later, the real numbers are nowhere close.

‘It’s being held back by two things: infrastructure and security,’ says Professor Heitor Carvalho, director of the Economic Research Centre at Angola’s Lusíada University, and a prominent voice on the potential economic impacts of the Lobito Corridor project.

There aren’t enough carriages, wagons or locomotives. Crossing sites, where trains travelling in opposite directions can pass each other, are too short. There are fears that some of the rail bridges may not be safe. And many of the railway’s 67 stations are little more than empty shells. Meanwhile, a lack of effective security means that drivers have to proceed at painfully slow speeds in case sections of track ahead have been looted by opportunistic locals. (In August, a train carrying a shipment of sulphur derailed in Moxico Province.)

Currently, just one or two mineral convoys a week are making their way to the port of Lobito.

As the passenger train from Luau trundles slowly westwards, the extent to which local communities rely on it – even in its reduced state – becomes apparent. At each stop, markets spontaneously erupt on the platforms, traders vying to make the most of the temporary influx of customers. Freshly fried doughnuts go for 50 kwanza (about £0.04) apiece, a stick of four giant grilled caterpillars for 100.

Many of the mud-and-thatch villages floating past the train windows appear mired in poverty, bypassed by the country’s enormous oil wealth. Visible reminders of the conflict are ubiquitous: homes without roofs, their walls riddled with bullet holes; lengths of old rail warped and twisted into helices; in one village, a whole locomotive lying abandoned on its side; in another, a rusting military tank overgrown by the tracks. Many of these communities, never wealthy, became increasingly isolated during the conflict. Until recently, travelling from Luau to the capital by road meant a week-long journey over chronically degraded roads still riddled with landmines.

In 2023, the government signed a deal with a US- and EU-backed consortium, the Lobito Atlantic Railway, to take over operations and restore the line to its full potential. The backers of the so-called Lobito Corridor have so far pledged some US$4 billion – the total price could reach around US$10 billion – toward upgrading the line, as well as a host of other projects along its route, including the construction of a new branch line into Zambia.

‘We’re not just laying tracks – we’re laying the groundwork for a better future for ordinary people,’ said Biden, calling it the largest ever rail investment by the USA in Africa. ‘It’s about the farmer who can get more food on more tables because of what we’re doing; the worker who can count on a living wage and safe conditions; the entrepreneur who is finally empowered to lead, innovate and build.’

Since the colonial era, outsiders have been building railways in Africa. Local people have sometimes benefited from these projects, yet just as often, the railways have functioned as tools of control and exploitation. More recently, Chinese infrastructure projects have come under fire for everything from the use of imported labour to a lack of concern over human rights and the environment. Projects often appear to have been designed with little thought to their impact on local people, and they frequently leave cash-strapped governments saddled with crippling debts. Angola alone owes Beijing some US$17 billion.

This time, Washington says, things will be different – and local people will be at the centre. Alongside upgrading the rail network, the Lobito Corridor project includes investments in green technology, mobile networks and agricultural value chains along the route. The White House says it could transform food security in the region. ‘They’ve said they’re going to take into account the population, so as activists, we want to follow up on that,’ said Marcelino Kienze Macole, the 68-year-old vice president of the Angola–DRC Chamber of Commerce and Industry. ‘They must see the poverty of the population. They must do something.’

Macole was speaking during a stopover in Huambo, a city of nearly 800,000 in Angola’s central highlands. He had travelled from the Congolese mining town of Lubumbashi to Lobito by train earlier in the week to lobby Angolan authorities for socio-economic development projects in the corridor. Now he was heading back. Complete with a restaurant car and first-class carriages with shared cabins and fold-down bunks, his train was somewhat more comfortable than the service from Luau.‘We want to start with infrastructure first because infrastructure is practically non-existent,’ he said. ‘There are no roads – and specifically, no agricultural service roads.’

If the project works as intended, billions of dollars’ worth of minerals will be shipped each year past some f the poorest communities in the country. But if those communities, most of them reliant on subsistence agriculture, can’t get their products to stations, they risk missing out on the railway’s benefits entirely.

‘These communities are living below the poverty line, but there’s so much potential for them to improve their circumstances,’ says Professor Carvalho. ‘But they don’t have ways to send their products to market. It’s a pattern in Angola.’ Carvalho argues that rather than investing in large-scale infrastructure in a handful of major stations, the project should focus on building more smaller stations and connecting them to centres of agricultural production via roads. ‘We should be using this investment to improve our local economy,’ he says. ‘But what’s being done isn’t enough – and it’s not being done in the right way.’

He also fears the railway’s mineral shipments could end up being prioritised to the detriment of passenger services and local freight.

Concerns also surround the involvement of Swiss commodity trader Trafigura, which is at the heart of the US-backed consortium. In January, the group and one of its former top executives were convicted in a Swiss court for bribing an Angolan official from the kleptocratic regime of former president José Eduardo dos Santos, in order to secure chartering and bunkering contracts. The deal, struck at a time when Trafigura enjoyed a near-monopoly on petroleum imports into Angola, resulted in a revenue shortfall of US$145 million, according to the Swiss Federal Criminal Court.

Another middleman involved in the company’s early investments along the corridor – investments that gave it a crucial foothold ahead of its successful 2023 concession bid – is currently serving a ten-year jail term for corruption in Brazil. ‘Trafigura is a very surprising choice by the Angolan government, as it was very closely linked to the Dos Santos regime… and also for the US, who convicted them for bribery in early 2024,’ says Adrià Budry Carbó, a researcher for the Swiss investigative non-profit Public Eye, whose November 2024 report exposed the tangled web of front companies and public officials through whom the company has operated in Angola.

‘When you consider that during Trafigura’s oil monopoly in the Dos Santos era, ordinary people failed to benefit from the crude wealth, it seems even less likely they’ll benefit from Angola being used as a transit route for Congolese minerals – especially when Trafigura’s involved,’ says Budry Carbó. ‘It’s extractivism at the highest level.’

Taking a ride along the Lobito Railway provides a window into a nation of contrasts. The landscape shifts constantly – from dense mopane forests and vast grasslands to rolling hills dotted with towering granitic batholiths and, nearer the coast, arid mountains and ravines scattered with prickly pear cacti. Flashes of extreme wealth exist alongside deep poverty.

There’s also a sense that both Angola and the Lobito Corridor are at a crossroads: the former looking to new partners as it seeks to diversify its economy and move on from civil war; the latter, as it faces questions over its relevance to local communities and contends with the emergence of a rival Chinese-backed railway project in East Africa. In the meantime, global demand for critical minerals is projected to explode in the coming decades, adding urgency to efforts to address the continent’s infrastructure deficit.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads…

By the time the train from Luau reaches its final stop in the town of Luena, darkness has fallen. After seven hours in the cramped carriage, the weary passengers are eager to disembark. But no sooner have the doors opened than a gang of a dozen youths leap inside, grabbing at watches, fishing in pockets, snatching unguarded luggage. There are shrieks as passengers shove their way to the exits. A woman in a colourful wrap grabs one of the thieves and begins beating him savagely while his friends continue robbing the remaining travellers. On the station platform, bored-looking security guards look on listlessly.

Once the pandemonium subsides and the gang disappears into the night, the last of the passengers leave the train. A few head for the town’s handful of small, rundown hotels, walking bag-in-hand along a wide boulevard lined with flamboyant trees. Others huddle in groups on the station steps, settling in for a night under the stars. In the morning, they’ll board a new train – continuing their journey west, through a country filled with both promise and uncertainty.