This unique hospital train provides much-needed affordable medical care in South Africa’s remote areas

Words & Photographs by Tommy Trenchard

The railway station in the town of Thaba Nchu in South Africa’s Free State Province is usually a sleepy spot. Passenger trains stopped coming here long ago, and only the occasional freight train now passes through on its way to the provincial capital, Bloemfontein.

The place carries an air of decay. Station buildings have been vandalised, their metal roofs stripped away for scrap. Even the bricks of the platform itself are gradually being removed by looters.

Yet on this morning in early spring, the station is a hive of activity. It’s barely 8am, but already dozens of people crowd the platform, with more arriving all the time. They come in ones and twos, walking slowly along footpaths through fields of tall, swaying grasses that glint with dew in the dawn light. Outside the gate, street vendors have set up stalls selling hot coffee and doughnuts, giving the place a fairground atmosphere.

The crowds have come for a chance to benefit from one of South Africa’s most cherished institutions – the Phelophepa healthcare train. For nearly 30 years, the Phelophepa has been travelling around the country bringing affordable healthcare to marginalised communities that have fallen through the gaps of an increasingly overstretched public health service. With a team of 22 travelling medical staff, it has so far treated some 14 million people.

‘The demand out there is just massive,’ says Bheki Mendlula, the train manager, who has been living onboard for the best part of a decade. ‘Everywhere we go, the train is a crowd puller. Where the Department of Health has challenges, the Phelophepa comes to the fore. At the end of the day, we want to make sure people have access to all basic health services.’

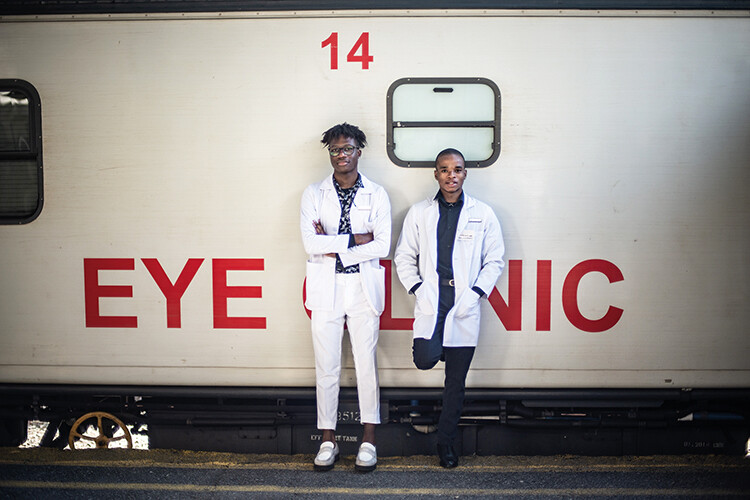

Run by the charity arm of Transnet, the national freight rail utility, the train started out in 1994 as a small mobile eye clinic, but has since grown into a fully functional health centre. As well as the eye clinic and a general health department, it now boasts a specialised dental carriage, a mental health department and an onboard pharmacy where staff dispense medicines to customers through the sliding train windows.

Out on the platform in Thaba Nchu, patients have come from far and wide with all manner of ailments. Many have been here since the previous day, spending the night wrapped in blankets on the platform to ensure they get a chance to see the doctors onboard.

‘The earliest bird catches the fattest worms,’ said one patient as he waited on the platform before dawn. He said he had come with the intention of getting as many of the train’s services as possible before it left town. He hoped to get a cancer screening, have his eyes and teeth checked, get his latest Covid-19 vaccine booster and have a checkup in the general health carriage.

‘People worry that if they don’t get to see us, they’ll have to wait until the next time the train passes through,’ explains Londeka Zulu, the manager of the train’s eye clinic and a long-term resident onboard.

Like many things in South Africa, healthcare is characterised by dramatic contrasts. The country invented the CAT scan and saw the first-ever human heart transplant. Yet, while a small minority of wealthy individuals can pay for access to world-class care from private institutions, the vast majority of South Africans must rely on a public health system that, although more affordable, lacks funding, personnel and facilities.

According to government figures, roughly 80 per cent of the country’s medical specialists work in the private sector, which serves less than a third of the population. The shortage of skilled personnel in the public sector is particularly severe in rural areas.

‘The allocation of clinics was done when the population was a certain size, and now it’s double that,’ says Jerry Mamome, the chairperson of Thaba Nchu’s healthcare forum, who doubles as the Phelophepa’s station manager whenever the train comes to town. ‘Staff at local health facilities are exhausted. They’re seeing twice the recommended number of patients every day.’

At the nearest clinic, the severely overworked manager explains that the facility is trying to serve more than 26,000 people with just five nurses and no doctors. Equipment and medicines are often in short supply and waiting times are long. For people living close to the poverty line, losing a day’s work while they wait around to eventually see a nurse who may or may not be able to help them isn’t an appealing option. Consequently, many go undiagnosed and untreated for years.

‘Diabetes, hypertension, TB, even cancer and HIV – the train is often first to flag these issues,’ says Mamome. ‘So it makes a huge difference, especially for the elderly.’

Some patients travel long distances to be treated on the Phelophepa. Whenever the train passes through areas near South Africa’s borders, staff find patients flooding in from neighbouring countries.

‘I’ve been going to clinics and hospitals for ten, maybe 15 years,’ says Mvula Mtolo, an unemployed father of three who suffers from chronic back pain and progressive vision loss, as he waits his turn aboard the Phelophepa. ‘But they haven’t been able to do anything. They just give you painkillers and send you away.’

Many of those on the platform have similar stories of months-long waiting lists, futile journeys to badly equipped hospitals in distant cities, trips to clinics they couldn’t afford and treatments that offered only temporary relief of their symptoms.

‘My tooth has been sore for a year now,’ says Nontsolo Losie as she waits to have a molar removed by the Phelophepa’s dentists. ‘Last time I went to a clinic, it took three months to get an appointment, and then they charged me 350 rand (£15). Here they’ll do it for free.’

The gaps in the country’s healthcare system aren’t distributed evenly. Eye care, for example, is particularly difficult to access. And so too is the treatment of mental health conditions.

‘For almost everyone we see, it’s their first time seeing a mental health professional,’ explains Ntombi Pukwana, the head of the train’s psychology department. ‘Sometimes there will be just one psychologist in a whole region, but they’ll be extremely tired and overworked, and they’ll have a four-month waiting list.’

The Phelophepa’s mental health department is becoming increasingly busy. The regions through which the train passes tend to be afflicted with a destructive combination of social issues that make mental health problems particularly prevalent: poverty, unemployment, sexual abuse, domestic violence and substance abuse. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, and this, combined with a gradual reduction in the stigmatisation of mental health, has seen a growing number of people coming forward to see Pukwana and her team.

‘It can be depressing at first, to think that you’re all these people have,’ she says. This is especially so given that the possibilities for follow-up care are either minimal or nonexistent once the train leaves town. Nevertheless, Pukwana believes the train can be a lifeline for some.

For the tight-knit team of medical and support staff who call the train home, the past few years have been particularly challenging. When the Covid-19 pandemic struck in the spring of 2020, the Phelophepa at first responded by offering a screening and testing service. Once the first vaccines emerged, the train became a mobile vaccination centre. The staff have carried out more than 200,000 tests and administered tens of thousands of doses of vaccine, alongside their normal work. But the pandemic had other knock-on effects. For years, South Africa’s railway network had been in a state of decline. Passenger journeys today amount to just a tiny fraction of what they did 30 years ago.

Infrastructure has been degraded or stolen and stations have fallen into disrepair. But during the pandemic, what had begun as the opportunistic looting and vandalism of railway equipment grew rapidly into a full-blown crisis. In 2021 alone, more than 1,000 kilometres of electrical cables were stripped from South Africa’s railways by thieves looking to sell the valuable copper wire inside them. According to the train’s onboard security detail, they frequently have to prevent looters from stealing parts of the train itself. By the beginning of 2022, the problem had become so acute that the government mooted banning all exports of scrap metal in an effort to bring the plunder under control.

‘On some of the branch lines, they’re even stealing the tracks themselves,’ says André Van Wyk, the Phelophepa’s driver, as he waits for a maintenance crew to clear a blockage caused by cable theft on the short journey between Thaba Nchu and the nearby town of Kroonstad. ‘We get this on a daily basis. Usually, we have to wait for hours.’

On its way around the country, the Phelophepa is now routinely delayed by dangling cables on the tracks, disrupting its schedules and leaving its patients unable to access the care they need. This disruption compounds the already considerable logistical challenges of running a health centre on wheels. Medicines, equipment and food have to be kept in stock at all times, wherever the train happens to be. Rotating groups of final-year medical students who support the train’s doctors need to be transported to and from universities all over South Africa every two weeks. At the same time, no sooner has the train arrived at one station than it must start sending out emissaries to begin spreading the word of its imminent arrival in the next one.

In the train’s cramped confines, everything is more difficult. Many of its more junior staff live in dormitories with barely enough room to get dressed in the morning. Its beleaguered kitchen team, operating out of a tiny space in carriage number 5, have to somehow prepare more than 100,000 meals a year for the train’s doctors, volunteers and contractors.

And yet, despite the challenges of train life, most of those who live onboard see it as a privilege – a rare opportunity to explore the farthest reaches of South Africa, to act as a force for good in the world, and to work alongside people from every corner of this diverse nation.

‘You get exposed to the whole country,’ says assistant catering manager Vumile Ndamase, whose kitchen team alone speak seven languages between them. ‘I’ve gotten to know places I never would have come to.’

‘We work with a very dedicated team who love what they’re doing,’ says Mendlula, the train manager. ‘We all share the same energy – it just rubs off naturally.’

To Mendlula, the Phelophepa represents a symbol of unity in a country still riven by divisions three decades after the end of apartheid. But he also sees it as a symbol of hope, at a time when the optimism of the Nelson Mandela years has given way to growing frustration over continuing inequality, unemployment, corruption and infrastructural decline. Despite the health service being overstretched and the railway network suffering rapid decay, the Phelophepa is still forging onwards.

‘People place their hopes in us,’ Mendlula says. ‘They call this the Train of Hope.’