Rory Walsh explores Devil’s Dyke, a South Downs beauty spot that Constable declared the ‘grandest view in the world’

Discovering Britain

Trail • Rural • South East England • 2.5 miles • Web guide

On a broad, undulating slope, clusters of people are enjoying a sunny day. Couples doze. Families graze picnics. An ice-cream van attracts a queue and day-trippers clamber from buses. ‘It feels like a beach,’ says Caroline Millar, Discovering Britain project manager and creator of this trail. But instead of sparkling sea, we are gazing upon a giant quilt of Sussex fields. On the horizon, we can make out the Isle of Wight. We are at Devil’s Dyke, sitting on a hill at the top of the South Downs.

The artist John Constable declared this spot ‘the grandest view in the world’. Vast views over the Sussex Weald ensure Devil’s Dyke is a popular place to walk, rest and play. Nearby, three information boards and a talking telescope illustrate local landmarks. Outside the Devil’s Dyke Hotel, the car park is full and the balcony teems with alfresco drinkers. Many have travelled inland from Brighton to see this view. But we are about to leave. Millar explains: ‘Most people who come here never actually visit Devil’s Dyke itself. It’s a shame because going into the actual dyke uncovers the story behind this beautiful scenery.’

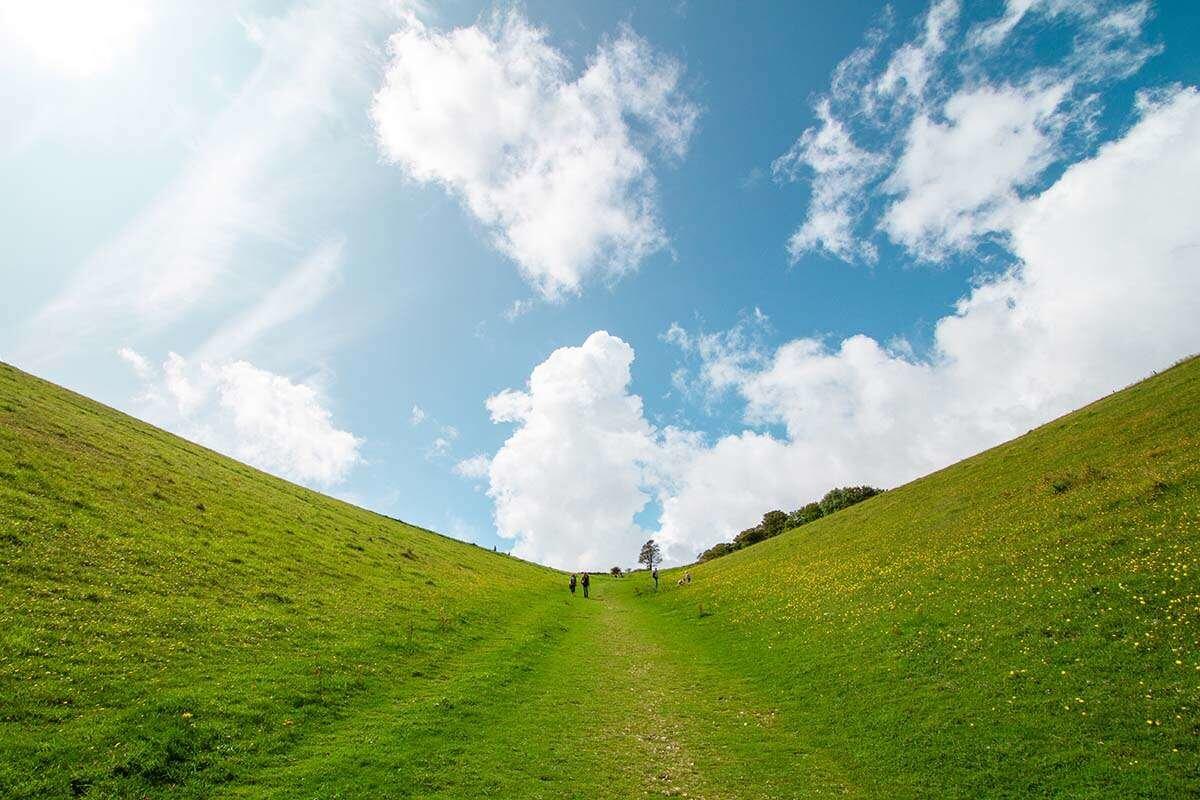

To reach the dyke, we turn away and join a bush-lined road. Millar leads the way to a bench beyond, where we take in a spectacular landscape. Devil’s Dyke is Britain’s deepest, widest, and longest dry valley. Its perfect V-shape unfurls below for just over half a mile. The dyke’s size has encouraged many myths. One story goes that it formed when the devil tried to flood the Weald’s many churches. While digging a trench towards the sea, he awoke an old woman. When she lit a candle to investigate, the devil abandoned his trench and fled.

To explore the true story of Devil’s Dyke, we descend the grassy slope towards the valley floor. Patches of bare chalk appear underfoot. We also find a few cubes of suspiciously modern-looking stone. ‘We’ll come back to these later,’ teases Millar. Standing on the valley floor feels like being in a drained reservoir. The grassy banks on either side loom like parted ocean waves. The dyke is 100 metres deep, twenty times more than the average swimming pool. Ripples continue as Millar explains the dyke’s aquatic geology.

The South Downs, including the dyke, are made of chalk. Chalk is permeable, so water passes through it, but when chalk freezes, it becomes impermeable. During the Ice Ages around 2.5 million years ago, the chalk froze solid with layers of soil and ice on top. When the weather briefly warmed during Ice Age summers, these top layers thawed. ‘Gravity did the rest,’ says Millar. ‘A sludgy mass of water, rocks and soil flowed across the frozen ground. It carved steep valleys into the soft chalk. In effect, we’re walking along the course of an ancient river.’ As we continue, the dyke bends to the left, demonstrating where the water met least resistance.

To leave the valley, we turn up the right-hand bank. A track wide enough for a car leads to a gate at the top. From here we pause and survey a mirrored view of the dyke. Earlier we were surrounded by other people but we’ve had the valley largely to ourselves. The trail becomes even more secluded as we go on. After crossing a cattle field, we turn left and follow a downhill path through some trees. From the panoramic vista at the start, through the valley, onto these winding woodland paths, the views are narrowing all the time. We could be the last drops of that ancient river, being funnelled away through the land.

We surface at a sizeable body of water, Poynings Lake. ‘Lakes like this are typical features of the Downs,’ says Millar. ‘They emerge as springs where the chalk meets impermeable clay soils.’ Such natural water sources encouraged people to settle here. The South Downs’ valleys are sprinkled with spring-line villages. From the lake we continue to a good example. The village of Poynings grew by the nearby spring. The single road is lined with a chain of pretty houses. On the left, a small path leads to a National Trust signpost. Here the landscape changes again.

A steep track crawls uphill. There are steps in places but it’s slow progress. ‘Don’t worry,’ says Millar, ‘the climb is worth it’. To our right the ground drops away, while ahead the huge view we enjoyed earlier gradually rises like a mirage. We pass through a gate then pause for a breather. Millar was right, the view is amazing. The focal point is off to our left, where the Downs appear as a series of huge rippled hills. Rudyard Kipling once called them the ‘blunt, bow-headed, whaleback Downs’. For her part, Millar compares them to a ruffled curtain or a sheet billowing in a breeze.

DISCOVER MORE OF BRITAIN

With their white cliffs and rolling green hills, the Downs are very visually appealing. It’s no wonder that from ancient myths about the Devil to Second World War propaganda, they have inspired many stories. Millar is fascinated by the way the Downs are portrayed in the arts. She cites the art of Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious. ‘Their paintings feature ancient paths, hillforts, Stone Age remains… they portray the Downs as timeless yet filled with history.’ Such layers of the past create a sense of scale and freedom. Perhaps this is what makes the Downs so inspiring and alluring?

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!

Devil’s Dyke certainly became a huge attraction for Victorian day-trippers enjoying their bank holidays. In 1893 a crowd of 30,000 visited on Whit Monday. Besides the views, they enjoyed a fairground, two bandstands, and a camera obscura. ‘Devil’s Dyke became a bit of a theme park,’ says Millar. The trail concludes with a curiosity from the era. Beyond the Devil’s Dyke Hotel is a stone ruin. It looks like an abandoned farmhouse. Children run in and out of the doorways and play peekaboo through missing windows. ‘This is thought to be an engine house for a funicular railway,’ says Millar.

Opened in 1897, the Steep Gauge Railway carried people up and down the hill to Poynings village. After our steep climb, the idea sounds tempting. There were other Victorian additions. ‘Remember those blocks we saw in the dyke?’ Millar asks. ‘They are remains of a cable car that spanned the valley.’ A local newspaper proudly reported a landscape transformed by tourism: ‘a casual visitor cannot fail to notice a marked improvement…to be found in place of the barren Downs.’ Today, the idea of ‘improving’ the ‘barren’ Downs seems absurd, if not reckless.

Now in the care of the National Trust, the landscape around Devil’s Dyke still bears a few scars of human involvement and reshaping. Given that our journey today has spanned millennia, such signs are inevitable. Overall though, Devil’s Dyke has largely returned to its natural state. Millar concludes: ‘The dyke isn’t really a “wild” place, but by turning away from the tourist view we can still be awed by fantastic natural scenery.’ On that note we complete the circle, leaving the Ice Age to join the queue at the ice cream van.

Go to the Discovering Britain website to find more hikes, short walks, or viewing points. Every landscape has a story to tell!