A major new study has identified 20 keystone species whose reintroduction would ensure that an additional 54 per cent of the planet’s land area regains its full complement of large mammals – but how practical is such an idea?

By Matt Maynard

Rody Álvarez doesn’t look like a puma hunter. Crouched over a camera trap on a steep, southern-beech-cloaked Patagonian hillside, he pulls an SD card from a camouflaged box, inserts it into his phone and waits. A pixelated tessellation appears to show a stilettoed pig licking a melted snowman. Fully loaded, a less surreal image emerges – a diminutive huemul deer, grazing on a car-wheel-sized salt block.

The bait and trap are Álvarez’s doing. Although he learnt to hunt and kill pumas from his contract-killer grandfather, today he works as a wildlife warden for Rewilding Chile (formerly Tompkins Conservation) in the northern Patagonian region of Aysén. Bolstering numbers of this critically endangered deer has became his life’s work, and now a new study argues that the animal might just hold the key to rewilding the entire southern tip of the Americas.

The south Andean deer – or huemul as it’s known locally – once inhabited a 166,149-square-kilometre-sized swathe at the southern tip of South America, in habitats ranging from dry Patagonian steppe to broad-leaved Magellanic forest. Today, the huemul has been reduced to 101 isolated subpopulations – a dismal total of 1,048–1,500 animals. Over and above warmer winters from climate breakdown, the fracturing of huemul territory has been precipitated by bacterial infections transmitted by introduced cattle, collisions with motor vehicles, dog attacks and the barbed-wire partitioning of habitats. Huemul existing in the smallest and remotest subpopulations numbering fewer than 20 are already considered extinct due to their poor genetic diversity and susceptibility to freak weather events.

More positively, Rewilding Chile believes that the overall population has been stabilised. The conservationists have strategically purchased land adjoining Cerro Castillo National Park in Las Horquetas Valley, where Álvarez has his camera traps. But according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), huemul are still in overall decline.

When it comes to rewilding, not all creatures are born equal. A new study suggests that huemul are one of 20 ‘keystone’ species – those most capable of restoring vast swathes of the planet to a state where all of the large mammals that should be present, are present. ‘An ecoregion‐based approach to restoring the world’s intact large mammal assemblages’, published in Ecography, claims that just 20 species have the potential to restore complete mammalian assemblages over an additional 54 per cent of the terrestrial realm. Today, only 15 per cent of the planet’s terrestrial ecosystems maintain their full complement of large mammals, an area smaller than the North American continent. But, according to the researchers, intact assemblages of large mammal species are important. Big mammals play a disproportionate role in the structure and composition of natural habitats. Their loss destabilises natural systems, while their recovery can restore ecological integrity.

‘As the world moves towards a focus on protecting more areas and being able to monitor this from space via satellites (both positive things), it is important to maintain a focus on also conserving and restoring biotic intactness – the full complement of living species that make each of the world’s ecoregions, or ecosystems of regional extent unique,’ says Carly Vynne, ecologist and lead author of the study. ‘Each ecoregion is unique because of the assemblages of species living there together. Large mammals are one of these groups – and one that is both more readily measured and often of particular ecological importance. As a group, large mammals tend to play out-sized roles in their ecosystems and in regulating ecosystem processes, food chain dynamics, vegetation structure and populations of other species.’

To find the 20 keystone species, the researchers first identified 298 large terrestrial mammals (any animal that weighs more than 15 kilograms). Using a range of data and previous studies to establish the ‘natural range’ of each species (that is, the area it inhabited before human influence – set at 1500 AD), they then identified the total area in which each of the species is the only missing large mammal. This was a practical decision, as areas with only one missing species are easier to fully restore. By focusing on places where these data overlap with large, continuous habitat blocks (ideal for restoration projects), they were able to identify the top 20 large mammal species whose reintroduction could best restore intact mammal assemblages.

The study is, admittedly, simplistic, incapable of fully taking into account the situation on the ground. The researchers identified several shortcomings, acknowledging that in some cases, restoring one species where many are absent might provide a greater ecological benefit than the restoration of a full faunal assemblage. In addition, when identifying areas most suitable for rewilding, they used satellite imagery, but land degradation caused by phenomena such as overgrazing may not be identifiable by satellite, so areas of habitat identified as suitable might be less so in the short to medium term.

Acknowledging this, the researchers sought out relevant experts for comment. The experts were prompted to choose from a larger list of missing mammals and suggest a best-fit habitat for their reintroduction based on local social, political and ecological realities. The results of this exercise differed from the data-driven findings, underscoring the importance of harmonising data with more nuanced information on the ground.

Nevertheless, the study points to the restoration potential of a small number of species. In a world where we can’t achieve everything, a narrower focus on keystone mammals could prove useful in certain locations. ‘For each place, it’s not just about the ecosystem functioning, but about what it means to have places in the world that are still biologically thriving – something that can be measured as still supporting all of the large mammals that were historically present,’ says Vynne. ‘A lot has to be going right for this to occur – there must be enough habitat, natural processes in place and a lack of direct threats – so conserving and restoring these places is a value that I think has great benefit for current and future generations of people to inherit.’

Rewilding key:

Total rewilding area: area across all global habitat types into which the mammal can be reintroduced; a country with a similar area is provided for comparison

Largest ecoregion: unique habitat type in which the greatest area of rewilding could occur

Dhole / Cuon alpinus

Biomes: Indomalayan and Palearctic

IUCN status: Endangered

Mature individuals: 949–2,215

Total rewilding area: 1,350,689 sq km ≈ Peru

Largest ecoregion: 669,102 sq km, East Siberian taiga (Russia, China)

‘Dholes are found across a range of habitats, but most populations are clustered in forested areas. They are habitat-sensitive and also require a substantial prey base of medium- to large-sized ungulate herbivores to thrive. Because they are pack-living animals, founder populations need to have an adequate number of packs (not just individuals) and genetic diversity for long-term viability. Furthermore, if such areas (identified as potential reintroduction sites) also support other predators, such as tiger, leopard, snow leopard and bear species, a prey-base surplus and adequate protection from negative anthropogenic factors will be key requirements. The East Siberian landscape, including the taiga forests of Russia and China, used to have dhole populations until perhaps 30–40 years ago. The last reliable record is from the 1980s. After concerted efforts from governments and NGOs, the dwindling populations of Amur tigers and Amur leopards in the region are somewhat stabilising/bouncing back. Although restoring dhole populations in much of the species’ former range may offer ecological benefits, it will likely be incredibly challenging to implement.’ Arjun Srivathsa, INSPIRE campus fellow specialising in the conservation ecology of carnivores

Brown bear / Ursus arctos

Biomes: Indomalayan, Palearctic and Nearctic

IUCN status: Least concern

Number of mature individuals: 110,000

Total rewilding area: 1,505,187 sq km ≈ Mongolia

Largest ecoregion: 603,824 sq km, East Canadian Shield taiga (Canada)

American bison / Bison bison

Biome: Nearctic

IUCN status: Near threatened

Mature individuals: 11,248–13,123

Total rewilding area: 1,306,978 sq km ≈ Peru

Largest ecoregion: 339,550sq km, Interior Alaska-Yukon lowland taiga (USA, Canada)

Pacarana / Dinomys branickii

Biome: Neotropic

IUCN status: Least concern

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 824,600 sq km ≈ Namibia

Largest ecoregion: 230,942 sq km, Juruá-Purus moist forests (Brazil)

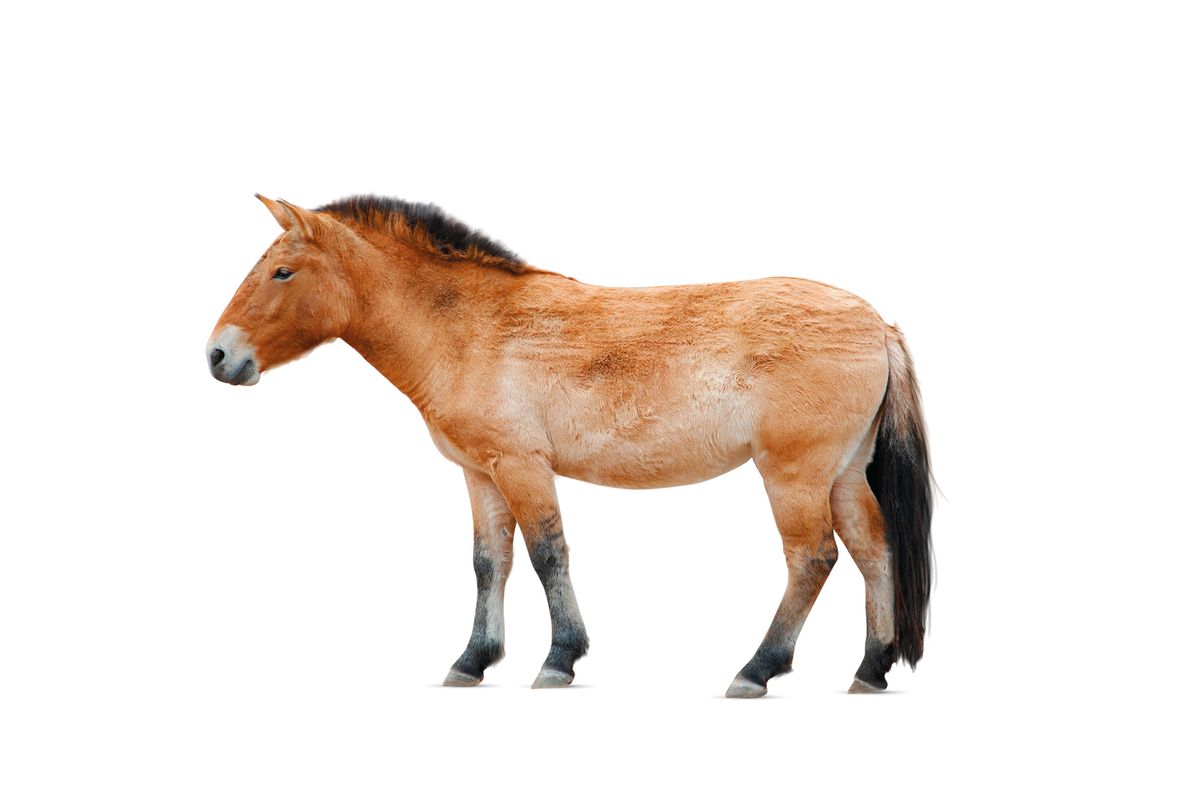

Przewalski’s horse / Equus ferus przewalskii

Biomes: Palearctic, Indomalayan

IUCN status: Endangered

Mature individuals: 178

Total rewilding area: 836,341 sq km ≈ Namibia

Largest ecoregion: 339,550 sq km, Cherskii-Kolyma mountain tundra (Russia)

‘Reintroducing wild horses to the Cherskii-Kolyma region would be wonderful. The horse is native to the region and across Eurasia and much of the Americas. Horses play important ecological roles. They affect vegetation structure, notably through their ability to feed on, and hence reduce, the dominance of coarse grasses. At the same time, horses are highly mobile and promote plant dispersal. Seeds temporarily cling to their bodies after feeding and are also

distributed to new locations through their faeces. This is an important process for maintaining plant populations in the landscape and also for helping plants to adapt to climate change, with wild horses helping them to migrate to new, more suitable microclimates. Overall, wild horses are expected to have positive effects on biodiversity by enhancing variability in vegetation structure and by facilitating plant dispersal.’ Jens-Christian Svenning, Centre for Biodiversity Dynamics in a Changing World, Aarhus University

Pampas deer / Ozotoceros bezoarticus

Biome: Neotropic

IUCN status: Near threatened

Mature individuals: 20,000–80,000

Total rewilding area: 684,500 sq km ≈ Myanmar

Largest ecoregion: 166,194 sq km, Dry chaco (Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil)

Jaguar / Panthera onca

Biomes: Nearctic, Neotropic

IUCN status: Near threatened

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 736,968 km2 ≈ Zambia

Largest ecoregion: 290,708 km2, Low monte (Argentina)

Eurasian beaver / Castor fiber

Biomes: Palearctic

IUCN status: Least concern

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 353,843 sq km ≈ Germany

Largest ecoregion: 169,074 sq km, Scandinavian and Russian taiga (Russia, Finland, Sweden, Norway)

European bison / Bison bonasus

Biomes: Palearctic

IUCN status: Near threatened

Mature individuals: 2,518

Total rewilding area: 482,47sq km≈ Turkmenistan

Largest ecoregion: 166,194sq km, Scandinavian and Russian taiga (Russian, Finland, Sweden, Norway)

Puma / Puma concolor

Biomes: Nearctic, Neotropic

IUCN status: Least concern

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 468,010 sq km ≈ Papua New Guinea

Largest ecoregion: 80,557 sq km, Napo moist forests (Peru, Ecuador, Colombia)

Tiger / Panthera tigris

Biomes: Indomalayan, Palearctic

IUCN status: Endangered

Mature individuals: 2,154–3,159

Total rewilding area: 449,835 sq km ≈ Sweden

Largest ecoregion: 336,590 sq km, East Siberian taiga (Russia, China)

Marsh deer / Blastocerus dichotomus

Biomes: Neotropic

IUCN status: Vulnerable

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 343,200 sq km ≈ Republic of the Congo

Largest ecoregion: 149,525 sq km, Cerrado grasslands, savannas and shrublands (Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia)

White-lipped peccary / Tayassu pecari

Biomes: Neotropic

IUCN status: Vulnerable

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 284,368 sq km ≈ Ecuador

Largest ecoregion: 38,669 sq km, Llanos flatlands (Venezuela, Colombia)

Reindeer / Rangifer tarandus

Biomes: Nearctic, Palearctic

IUCN status: Vulnerable

Mature individuals: 2,890,400

Total rewilding area: 231,120 sq km ≈ Laos

Largest ecoregion: 103,224 sq km, Scandinavian and Russian taiga (Russia, Sweden, Finland, Norway)

Dama gazelle / Nanger dama

Biomes: Palearctic

IUCN status: Critically endangered

Mature individuals: 100–200

Total rewilding area: 240,400 sq km ≈ Uganda

Largest ecoregion: 105,350 sq km2 South Sahara Desert (Western Sahara, Mauritania, Mali, Algeria, Niger, Chad, Egypt)

Wolverine / Gulo gulo

Biomes: Nearctic, Palearctic

UCN status: Least concern

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 266,103 sq km ≈ Gabon

Largest ecoregion: 250,142 sq km, East Canadian forests (Canada)

Patagonian huemul / Hippocamelus bisulcus

Biomes: Neotropic

IUCN status: Endangered

Mature individuals: 1,048–1500

Total rewilding area: 166,149 km2 ≈ Tunisia

Largest ecoregion: 73,291 km2, Patagonian steppe (Argentina, Chile, Falkland Islands)

‘Huemul have evolved for thousands of years in a close relationship with the forest, acting as native gardeners. The paper identifies a large block of ecoregions where the species needs to be reintroduced and managed. By concentrating this rewilding effort on the prime area for the species, characterised by Nothofagus (southern beech) forests, we will be able to secure areas that could serve as population sources for reintroduction programmes. Rewilding huemul on the Patagonian steppe [as a whole] needs to be selective and carefully enacted. Today, this habitat is dramatically different to when south Andean deer inhabited it a century or more ago. This ecoregion suffered more as a consequence of historical grazing by millions of livestock (both sheep and cows), causing severe erosion and desertification. For me, the Patagonian steppe could be a complementary stage once you have already secured the principal populations and initiated the work in transitional areas.’ Cristían Saucedo, wildlife director, Rewilding Chile

Hippopotamus / Hippopotamus amphibius

Biomes: Afrotropic

IUCN status: Vulnerable

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 206,608 sq km ≈ Belarus

Largest ecoregion: 43,645 sq km, Western Congolian swamp forests (Republic of the

Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo)

‘Hippos are generalists in terms of their foraging behavior (they eat grass) but I’d consider them to be habitat specialists because they require freshwater as a critical aspect of their ecology and require standing water to survive, particularly during the dry season. There is a clear need to protect common hippos and their wetland habitat across the subcontinent. Hippo populations are declining in many countries, with the largest declines in West Africa. The most pressing threats are habitat loss and degradation (often in the form of freshwater diversion), and unregulated hunting (both for meat and, increasingly, for ivory found in canine teeth). The good news is that hippo populations are present in 28 African countries, so our priority should be protecting the existing populations, not reintroductions, to promote population recovery in areas where declines have been most severe. Reintroductions of hippos (in contrast to natural expansions of existing populations based on improved conservation efforts and robust landscape connectivity) are costly, risky and an inefficient use of extremely limited conservation resources for hippos everywhere.’ Rebecca Lewison, co-chair of the IUCN’s Hippo Specialist Group

American black bear / Ursus americanus

Biomes: Nearctic, Neotropic

IUCN status: Vulnerable

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 224,164 sq km ≈ Laos

Largest ecoregion: 128,313 sq km, Canadian low Arctic tundra (Canada)

Moose / Alces alces

Biomes: Nearctic, Palearctic

IUCN status: Least concern

Mature individuals: Unknown

Total rewilding area: 154,482 sq km ≈ Bangladesh

Largest ecoregion: 40,350 sq km, Northwest territories taiga (Canada)