Almost 70 countries sign the first-ever international agreement to protect high seas from ecological devastation

By

It’s official: after two decades of negotiations, a historic UN treaty to protect international waters from overfishing, oil drilling and climate change has been confirmed by the signatures of 66 countries last night (September 20).

With signing expected to continue until 2025, hopes are high that this could present a major turning point for a global effort towards marine conservation.

The Treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) will create a framework for member states to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) to shield key habitats from ‘extractive activities’.

The high seas cover more than half of the earth’s surface and represent two-thirds of the global ocean. Yet currently, only one per cent of the high seas are under legal protection.

Rebecca Hubbard is the director of the High Seas Alliance (HSA), a group of more than 50 NGOs that have led the efforts for the BBNJ treaty for the last decade. She told Geographical: ‘For many years, we have not had the laws and protections that we need to properly protect life in the high seas, which means that this really important environment has been exposed to extreme pressure.’

She emphasised the key role the ocean plays in supporting life on our planet. ‘It is essentially a massive life support system for us all,’ she said. ‘Even if you’ve never been anywhere near the ocean, the high seas are critical for our survival.’

Roughly half of our oxygen comes from the seas, according to National Ocean Service data. It also absorbs a quarter of all carbon dioxide and 90 per cent of the excess heat, leading the UN to name it our ‘greatest ally against climate change’.

Related links:

Over the course of its long-winded path to adoption, the high seas treaty appears to have gathered global consensus, with more than 190 countries expressing their support of its formal adoption by the UN on Monday (September 19). The UK and Northern Ireland, the USA, the EU, and Australia signed yesterday, with more countries set to sign the agreement today.

‘We’re obviously thrilled that we’ve finally achieved the treaty. But it is actually only the beginning of the path to getting protection in the water,’ Hubbard noted. The treaty will only come into effect once 60 countries have written it into their own laws or acted upon it. The global community will need to move quickly if it is to make good on the UN’s ‘30 by 30’ pledge – protecting 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030.

The next steps include identifying and putting in place MPAs for the most vulnerable and important ecosystems of the high seas.

HSA has already started a list of areas with ‘unique biodiversity values’ that are ‘representative of the kinds of sites we need to be acting really quickly to protect’, said Hubbard. Her hope is that these areas will soon become a part of the first wave of MPAs.

The suggestions include:

Sargasso Sea

The only sea with no land borders, the Sargasso Sea is enclosed instead by the North Atlantic Gyre, the rotating meeting place of four Atlantic ocean currents. The sea is sometimes called ‘the golden floating rainforest’ because of the yellow Sargassum seaweed on its surface.

The seaweed absorbs a huge amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and produces oxygen.

Endangered species like the green, hawksbill, loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley turtle use the area as a nursery for hatchlings, and the area is home to a highly specialised and unique ecosystem of marine wildlife.

But the area also contains one of the five notorious ocean garbage patches. Some studies have estimated there are around 200,000 bits of trash per square kilometre in the Sargasso Sea, most of it in the form of microplastics. These make their way through the food chain, putting sea life and, ultimately, human health at risk.

The HSA hopes an MPA under the high seas treaty could protect the deterioration of the site, which also supports the whale-watching industries of the Caribbean has a significant knock-on effect on global marine life.

“It’s imperative that the Sargasso Sea receives urgent protection on a wide scale,” the HSA commented.

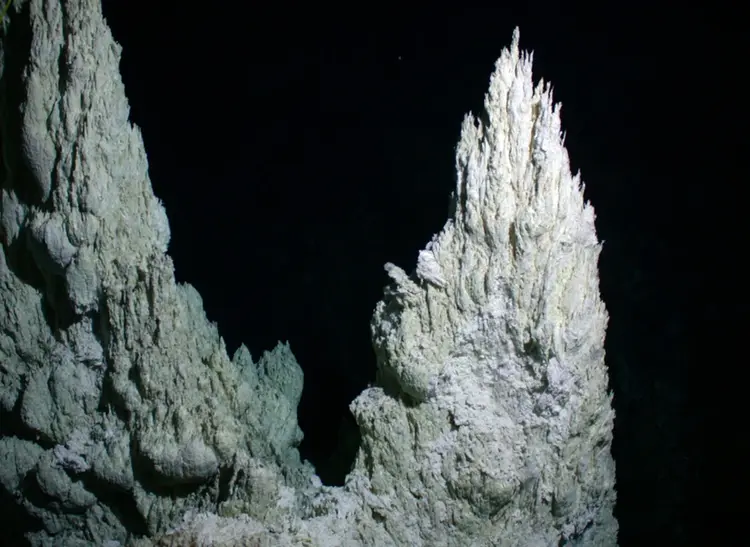

The Lost City Hydrothermal Fields

An eerie skyline of white, geothermal chimneys inspired the name of the Lost City. The 250,000-year-old structures, which range from one to 100 metres in height, are located in the mid-Atlantic ridge on the slopes of the Atlantis seamount.

The columns are formed of serpentinite rock, a phenomenon where water below the seafloor reacts with the rock in the Earth’s mantle. The chemical process causes hydrogen, methane and heat to spew out in highly alkaline water from vents in the seafloor.

This unique environment has given rise to trillions of bacteria and microorganisms that some scientists believe hold the key to understanding the origins of life – and to finding traces of life on other planets.

Areas close to the Lost City are currently being explored for cobalt, manganese, gold and other heavy metals, putting the area at risk from far-reaching sediment plumes.

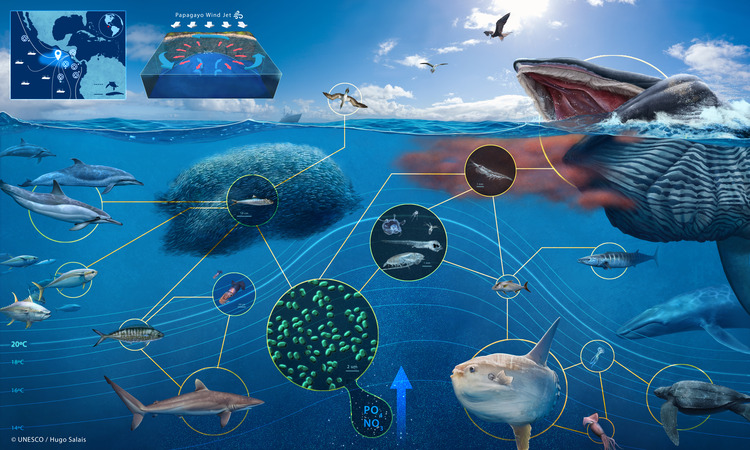

The Costa Rica Thermal Dome

Hubbard names the Thermal Dome more of ‘a phenomenal ecological wonder’ than a fixed location. A yearly event in the Eastern Pacific, the Dome occurs when seasonal winds drive warmer currents from the coast into the colder deep-sea currents.

Nutrient-rich water from the depths of the ocean is pushed to the surface in a dome-shaped swelling, which creates the perfect conditions for blue-green algae to flourish. This attracts trillions of phytoplankton, zooplankton and krill, kickstarting ‘one of the richest marine food webs known to science’, according to HSA.

The algae also act as a significant carbon trap that could be critical in the fight against climate change.

The phenomenon moves from year to year and varies in size from 300 to 15,000 kilometres, which makes it hard to protect. However, wherever it appears, it supports an estimated 1,400 blue whales and provides a migration corridor for dolphins, sharks, rays, marlins and sea turtles.

These creatures are permanently at risk of becoming bycatch as overfishing in the region is rife. Shipping traffic on its way to the Panama Canal, ship strikes and plastic pollution are all threats too.

The high seas treaty will not immediately ban fishing or shipping vessels from entering the region, but it could provide a valuable framework for the regulation of these industries.

Saya de Malha Bank

Another biodiversity hotspot, the Saya de Malha Bank is famous for the carnival of colourful tropical fish, rare sea mammals and corals. Located in the Indian Ocean and forming a part of the Mascarene Plateau, the bank consists of a shallow ridge between Seychelles and Réunion.

Saya de Malha is a globally significant underwater landscape because it is the largest seagrass meadow on the planet. This gently swaying grassland sucks up carbon 35 times faster than tropical rainforests. Only 0.2 per cent of the world’s oceans feature seagrass meadows, yet they take up almost 10 per cent of its carbon every year, according to a report by the World Resources Institute.

Seagrass has been touted by the UN as ‘the secret weapon against climate change’, which should be reason enough to prioritise the protection of this area. The vital plant is vulnerable to changes sea eutrophication – the increased presence of nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural and sewage run-off – and temperature, with 21 per cent of species already classified as endangered.

The suggestions also include the Salas y Goméz & Nazca ridges, the Walvis Ridge, the Emperor Seamounts and the Lord Howe Rise.

The MPAs will not come into effect automatically once the treaty is ratified. ‘The symbolic signing of the treaty is an important step – but we have to be very careful,’ said Jonny Hughes from the Blue Marine Foundation, one of the members of the HSA. He argued that once the treaty was ratified, the hard would begin. NGOs would need to work hard to hold government to account. ‘We need to make sure governments aren’t making grandiose statements about marine protection – but not following through with their actions’ he said.

Nonetheless Hubbard is optimistic about the progress of the treaty so far. She said: ‘The really upstanding and extraordinary thing about the high seas treaty is that it really demonstrates that global leaders are willing to come together to act to protect biodiversity and to look after the good of all people around the planet.’

She added: ‘It is truly a light in the dark.’