One of the world’s biggest infrastructure projects is racing ahead, despite court orders to halt construction. Conservationists fear that a train line looping around the Yucatán Peninsula is going to wreak havoc on the fragile Mexican cenotes, the jungle above and the coral reefs that border the coast

By

In 19 June this year, Mexico’s First District Court issued an order to halt construction on Section 5 South of Tren Maya – the Mayan Train. It’s at least the sixth time since 2020 that a suspension has been granted by the courts for a project that could have disastrous consequences for both the jungle of the Yucatán Peninsula and the freshwater aquifer that lies below it – and it has been summarily ignored.

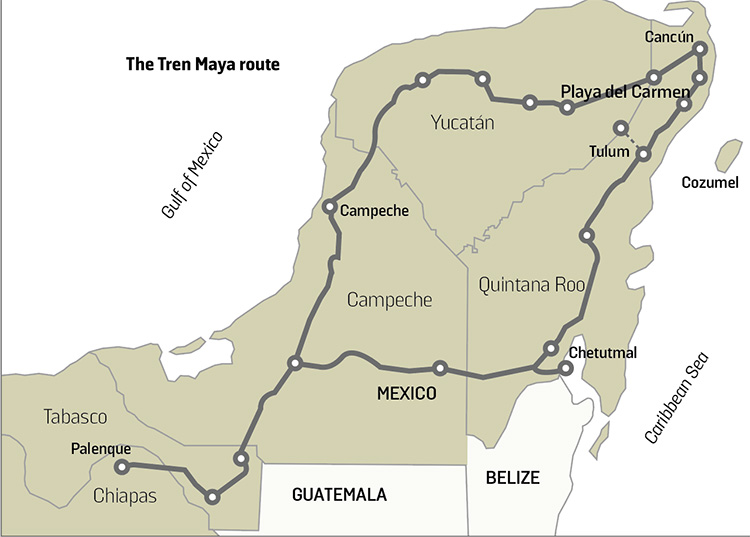

Tren Maya is the legacy of outgoing Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (or AMLO, as he’s commonly known), who announced the 1,554-kilometre mega-project upon his election in 2018. The railway stretches from the tourist resort of Cancún in the northwestern reaches of the peninsula to the economically deprived city of Palenque in the south, traversing the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo.

The Mexican government argues that the project received overwhelming public approval in a 2019 referendum, with 92.5 per cent of the people who participated in the public consultation voting in favour. In fact, just 100,940 people voted – less than 2.4 per cent of the 3.5 million people registered on the electoral rolls of the five states through which the train passes, and the Indigenous descendants of the Maya say they weren’t consulted at all – they called the process a ‘simulation’.

Indigenous community representatives had previously issued a joint statement rejecting the consultation, which they saw as a violation of their territorial rights. A temporary halt to the railway’s construction was subsequently granted following a court order obtained by the Consejo Regional Indígena y Popular de Xpujil (Regional Indigenous and Popular Council of Xpujil), on the grounds that failure to consult Indigenous peoples is a violation of international law.

‘It is not permissible for any person outside the Yucatán Peninsula to try to decide what can or cannot be done in our territories, just as we will never try to decide what will be done with their property, rights and possessions,’ they wrote. ‘Officially, there is no authority that has sat down to talk with us, despite the fact that the physical work is intended to be established in our territories… [the train] has nothing Mayan, nor any benefit to the Mayan population. We do not want to be a Cancún or Rivera Maya, where hotel chains, restaurant transportation chains are the only beneficiaries.’

Despite the temporary inconvenience to his plans, López Obrador pushed ahead with the development, handing Tren Maya’s construction and operation to the military as a ‘national security project’, with a budget raised through tourist taxes of around 120 billion Mexican pesos – about US$7.2billion. Construction began in June 2020 and the first, 475-kilometre section of the route, between Cancún and Campeche, began operating in December 2023, a remarkable turnaround for such a huge project – a comparable initiative, India’s 500-kilometre Mumbai–Ahmedabad High Speed Rail Corridor, which also broke ground in 2020, isn’t expected to be operational before 2028.

As of 2024, the budget has almost quadrupled to about US$28.5billion, but the cost to the environment is proving to be far greater, in large part due to the rerouting of ‘Section 5’ between Cancún and Tulum. The original plan for much of the train line’s route was to follow the Yucatán’s existing highways and train lines – as is the case with the Cancún–Campeche section – and therefore, Section 5 would follow Highway 307, which runs along the peninsula’s eastern coast from Cancún to Chetumal. In 2021, however, the owners of hotels along the route lobbied López Obrador’s government to prevent the construction of the 121-kilometre stretch of the railway through their backyards.

For the sake of 20 metres of frontage, the reconstruction of some resort entrances and the temporary inconvenience of noise pollution, the railway route was pushed several kilometres inland through the jungle. Despite promises from López Obrador before breaking ground that not a single tree would be felled, an estimated ten million have subsequently been cut down, forming an unsightly 121-kilometre, 70-metre-wide scar through previously pristine rainforest.

The redirection also drove construction across some of Yucatán’s famous cenotes, the natural sinkholes that descend through the karst landscape into the second-longest underwater cave system in the world – and Mexico’s largest and most important freshwater aquifer.

A popular tourist attraction for divers and snorkellers, there are some 10,000 cenotes – a Spanish name for the ancient Mayan word dzonot or ts’ono’ot, meaning ‘well’ – dotted around the peninsula. Some are deep holes surrounded by jungle and filled with organic detritus, others are little larger in diameter than puddles through which trained divers can descend into vast stalactite- and stalagmite-filled caverns, formed over millions of years and virtually untouched by modern humans.

Section 5 South passes directly over some of the most important parts of the aquifer, including the Sac Actun and Dos Ojos cave network, which are together at least 386 kilometres in length and only discovered to be connected in 2018, forming the second-largest cave system in Mexico behind the 436-kilometre Ox Bel Ha. Exploration is limited by the technical challenges of diving through the caves, and it’s possible that all the systems are connected at some as yet undiscovered level. The presence of salt water in its depths implies that the freshwater aquifer is connected to the ocean, meaning any substance deposited into the aquifer will eventually find its way downstream towards the coastal mangrove forests and the coral reefs of the Riviera Maya.

In a bid to prevent damage to the cenotes, 67.7 kilometres of the railway is being constructed on a viaduct raised 18 metres above ground level. To accomplish this, some 17,000 steel-reinforced concrete pillars have been driven into the ground to a depth of around 25 metres. Formed by the continuous dissolution and precipitation of soluble minerals such as limestone, karst isn’t a particularly stable foundation for heavy-duty construction; in fact, given its porous, Swiss-cheese-like nature, there’s no guarantee the pillars will even sit on solid ground.

Water treatment consultant Guillermo D Christy and cave diver Pepe Urbina are among the most vocal opponents of the train’s redirection. They are senior figures in the campaign group Cenotes Urbanos, one of several united under the banner of Sélvame del Tren (Save Me From the Train, a play on the Spanish words salva, meaning ‘save’ and selva, meaning ‘jungle’). Both are sceptical of the viaduct’s safety. ‘The cave system here is in continuous collapse,’ says Urbina. ‘They drill a hole, put a steel cylinder in the structure and fill that with concrete. The problem with that is that for 200 metres – maybe more – under the limestone you won’t find ground underneath. It’s another cave. That’s why they need so many pillars – they are putting in a bed of nails.’

‘It’s not a question of whether or not there will be karst soil subsidence affecting the elevated train viaduct,’ adds Christy, ‘the question is when? The high concentration of chlorides [in the water] is already corroding the steel of the jackets, and may already be corroding the [internal] steel rods of the pile assembly.’ As if proof were needed, on 13 June, a small section of ground beneath the viaduct gave way close to the site of the new train station being built in Tulum.

Overground, the loss of habitat is plain to see, but the destruction underground is less visible and potentially much more damaging because the water that flows through the aquifer below supports the flora and fauna of the jungle above. Caverns – and the ecoystems contained within them – previously thriving in total darkness are now open to the sunlight; concrete overspill has been poured directly into the caves and their waters; the steel casings used to house the pillars as they set is already corroding, with a steady stream of iron oxide now detectable in the water supply.

‘There are different effects from the moment the cenotes lost the vegetation cover over them – the temperature and humidity are altered,’ says Christy. ‘Some caverns have been filled with stone material, some lost their sinkholes when they were excavated and others are crossed with perforations from the pillars of concrete and steel,’ he adds. ‘These perforations could also affect the flows of fresh and salt water.

‘The government talks about transporting cargo with this train and states that 80 per cent will be hydrocarbons from Petróleos Mexicanos,’ Christy continues. ‘Let’s imagine what a diesel or gasoline spill could be like on the train line. Everything that permeates the jungle eventually reverberates downstream, to the coast, affecting its passage, jungle, mangroves, underground rivers, the reef.’

HUMAN REMAINS

There is also the potential loss of archaeological remains from a civilisation dating back to a time when the cave systems were above ground and dry. Sea levels during the last glacial maximum 22,000 years ago were 120 metres lower than the present day. Human remains – from burial, misadventure and human sacrifice – have been found in the cenotes since they were first explored in the early 20th century. The more distant reaches, however, have only been properly explored since 1987, and then only by a handful of individuals with the equipment, training – and nerve – to do so. Among their finds are the oldest and most genetically intact human remains ever found on the American continents – the discovery in 2001 of a 13,600-year-old female skeleton and the discovery of a 12,000–13,000-year-old young girl’s skeleton six years later forced archaeologists to completely rethink both the place of origin and timescale of arrival of the first humans to settle in South America.

‘The area of Section 5 South is the site with the highest concentration of caves in the state of Quintana Roo,’ says Christy. ‘In this area, the ten oldest bones on the American continent have been recovered, as well as palaeontological pieces from the ice age. The geological information that this place houses is of incalculable value when recording climatological information from the history of the Earth. How much information, human, archaeological and palaeontological remains have been lost with the illegal passage of this work? We will never know.’

FROM COURT TO CONSTRUCTION

There have been at least 25 legal attempts to halt the railway’s development – but its designation as a national security project means court rulings have little impact. In March 2022, a three-month suspension order was granted following a successful ‘Amparo’ (appeal to the Mexican Constitution) filed by a group of cave divers who pointed out the government didn’t have a manifestación de impacto ambiental (environmental impact statement). President López Obrador said that he was never notified of the order, calling the protesters ‘people without convictions and without moral scruples.’

As with all the others, however, the latest court order to suspend construction has had no impact, and judicial technicalities mean there’s no penalty for its continuation. ‘The government ignores the judges’ determinations,’ says Playa del Carmen-based lawyer, Raul Aldama, who filed one of the Amparos himself, ‘so a special procedure must be carried out to determine that there is a contempt of court, and as long as it is not determined that there is contempt of court, [the continuation of the work] is not illegal.

‘But it has always been illegal,’ he adds, ‘for not having environmental procedures before starting construction work. The political power exercised against the judges has not helped to stop the work; there is a narrative from the president that the judiciary is corrupt.’

Work continues apace to force through AMLO’s vision before the end of 2024 and his term as president. Sélvame del Tren’s campaigners were hopeful their message of ecocide and the erosion of Indigenous people’s rights would have an effect on the June presidential elections, but their pleas fell on the deaf ears of a population that has been promised only work and prosperity by the new train. AMLO’s newly elected replacement, Mexico’s first female president and self-proclaimed environmentalist Claudia Sheinbaum, has dismissed the campaigners’ criticism as having ‘a lot to do with politics and little to do with knowledge.’ Widely regarded as AMLO’s appointed successor and unlikely to challenge his legacy – she was his secretary of the environment during his tenure as governor of Mexico City – in the week prior to election day, she reportedly met with the leaders of Belize and Guatemala to discuss extending the railway south into Central America.

López Obrador, who presents himself as a man of the people – and, indeed, enjoys a high level of popular support – justified the railway’s construction with promises that connecting the region’s coastal resorts with inland communities and the ancient Mayan sites from which the train takes (some would say ‘appropriates’) its name would create hundreds of thousands of new jobs and employment opportunities within the tourism industry. This would bring with it attractive investment opportunities for future development, which the campaigners say will prove ruinous in the long term.

Barring some major incident – which may not be unlikely, as the rainy season gets underway – the completion of the railway is all but inevitable. Campaigners such as Christy and Urbina are turning their attention towards the problems that mass development along Section 5 South will bring to the region. Hotels are already under construction and land is being purchased – or expropriated – at an alarming rate. Under Mexican law, if a plot of land is consumed by fire, it may be repurposed for development, and it appears conveniently situated plots of land are regularly catching fire.

‘The Basin Council of the Yucatán Peninsula estimates that due to these works, by the year 2030, around two million more people will be coming to live on the peninsula in the main cities,’ says Christy. ‘This new population will demand health services and housing, and the water [they] will require is approximately the same volume of water that is currently extracted from the aquifer.

‘We will be, and in some points such as Tulum already are, in a process of water stress. We will run out of fresh water due to excess extraction, the intrusion of seawater will salt the wells. In urban areas, desalination plants will be implemented, but in jungle areas, a process of deforestation and defaunation will be caused.’

‘We are killing the aquifer,’ says Urbina. ‘We have the technology to do things better, but it’s not useful for political reasons. They need to build a train just to show you that they built a train – that’s it, that’s why it’s being imposed without respecting any environmental laws.

‘It’s an area that should be protected as a patrimony to human heritage,’ he adds. ‘The jungle, the water, everything should be treated like a sacred area. And we are destroying it, one golf course at a time.’