Academic and conservation innovator Paul Jepson joins the growing number of tourists visiting Antarctica and proposes a radical manifesto for its future

Telling friends I was going on an Antarctic expedition cruise elicited responses of, ‘Wow, you lucky thing, a trip of a lifetime!’ They said it could be a sublime experience. And it was. It was like a journey to a sister-world aboard an interplanetary craft. It also offered an opportunity to consider whether the rise of Antarctic cruise tourism could become a source of harm or a force for good.

I hadn’t appreciated the role of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) in creating a unique world within its flow – one that’s comparatively slow and simple, governed by currents, water masses with different densities, extreme cold and long periods of darkness. Relatively few lifeforms from our world have adapted to this world, but those that have are abundant, quirky and beautiful.

The ACC thermally isolates Antarctica by creating a dynamic boundary between the warmer sub-tropical waters and the colder southern waters. As we navigated the convergence aboard the 100-passenger Ortelius, a former research ship, my sense of journeying into another world was reinforced by a strict biosafety regime: we spent hours removing every seed, hair and sand grain from our clothes and packs (and having the guides repeat the checking process) under the threat that the whole ship could be turned away if five of us failed the inspection by a South Georgian official. Adding to this other-worldliness was the realisation that no one owned or inhabited the place; there were only scientific outposts, and ‘landing’ was strictly controlled.

It was the narrative of exploration and Sir Earnest Shackleton’s heroism that dominated our voyage from the Falklands to the Antarctic Peninsula. Reaching South Georgia, stories of exploration and endurance intermingled with the more troubling story of the industrialised killing of whales and seals. The era of Antarctica’s discovery was also an era of killing its megafauna for products that ‘greased the gears’ of industrialising countries in the years before the scaling up of petroleum and synthetic products.

REGULATION

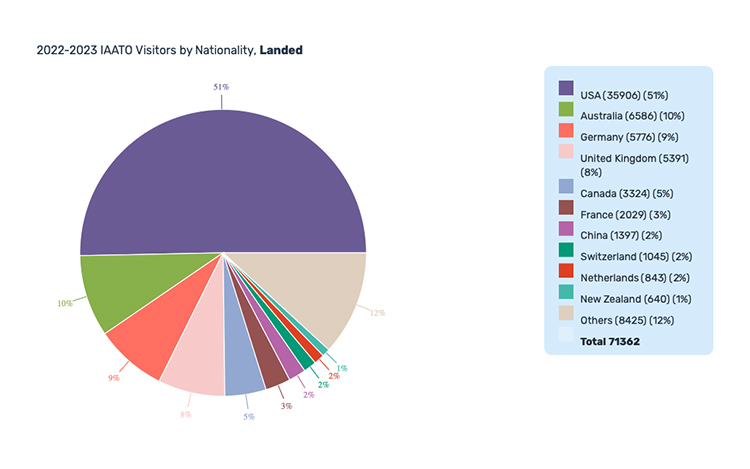

By good fortune, one of the ship’s guides was a German bureaucrat responsible for implementing Germany’s responsibilities under the Antarctic Treaty. This binding international agreement has its origins in science expeditions associated with the Geophysical Year of 1957, which, in the context of growing Cold War geopolitical worries, led to the global community declaring the continent a place of ‘scientific research and peaceful purpose’. In 1991, at the time of the Rio Earth Summit, a strict environmental protocol was added to the treaty, significantly restricting the activities permitted in Antarctica. Since the commissioning of the Lindblad Explorer in 1972, tourists have ventured into this world. Until a decade ago, the cost was prohibitive for most, and numbers were insignificant, but this has all changed. Last year, more than 100,000 tourists crossed the ACC aboard 700 vessels, ranging from 100-berth expedition ships to luxury cruise liners. China is building a fleet of ten polar cruise ships, which will add to the numbers.

Some treaty countries worry about the potential negative environmental impacts of the booming Antarctic tourism era, but it’s up to individual countries to decide whether to regulate the activities of cruise ships sailing under their flag. Fearing future regulation under the treaty, the cruise industry created the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO). The level of industry self-regulation is impressive: They operate a one-ship-at-a-time booking system for islands, bays, and channels, limit landings to 100 passengers, and have agreed to strict visit guidelines for every penguin colony.

One evening we saw the swanky Scenic Eclipse cruise ship glide by with its 228 passengers – one of the new generation of extremely luxurious vessels that have added a trip to the frozen south to their itineraries. A few weeks after my return, the Channel 5 series Cruising with Susan Calman offered me an unexpected peek into life aboard the Scenic Eclipse. It’s marketed as the world’s first ‘discovery yacht’, blending ultra-luxury with tailored explorations on foot and by Zodiac, kayak, foot, paddleboard, helicopter and even the ship’s own submarine!

Whether luxurious or simply comfortable, Antarctic cruises are united by a common marketing narrative: a journey into a pristine world marked by vastness, beauty and otherness – a world few have the privilege of witnessing, where wildlife abounds and has right of way, where sublime experiences kindle a desire to protect the sanctity of this precious and awe-inspiring world.

This is all commendable, but the cynic in me wondered if these narratives of heroic expeditions, self-restraint and inspired guardianship helped shield the industry from external regulation and scrutiny over the carbon footprint of Antarctic cruises – roughly equivalent to a person’s annual carbon emissions. I was saddened to see guides relegated to the role of ‘penguin police’ rather than being empowered as storytellers and educators who could catalyse optimistic visions for the Antarctic. This led me to question whether entrenched business interests are preventing IAATO from actively shaping polar tourism as a force for planetary good.

RESILIENCE

During the voyage, I read a scientific paper that posited that ‘the impacts of climate change on Antarctica are difficult to discern because they are masked by the recovery of the ecosystem’. In our era of eco-anxiety, the notion that ecosystem recovery might ameliorate the effects of climate change offers a narrative of hope and confidence in the future.

I’d begun to feel this sense of hope in the future during our first Zodiac cruise along the rocky shores of Right Whale Bay. Tiny Wilson’s petrels danced around us as southern giant petrels floated by, but it was the drab and unassuming, sparrow-sized South Georgia pipit that excited the birders. Found only on South Georgia, the most southerly songbird species was, until recently, confined to a few rat-free offshore islands. Rats were brought by sealers and whalers in the 18th and 19th centuries, and had a devastating impact on the land- and seabirds, preying on their eggs and chicks. In 2011, the South Georgia Heritage Trust organised a rat eradication programme, executed in several phases, that achieved full success by 2018. The pipit has recovered quickly, serving as a modest symbol of the potential for human-led conservation efforts to reverse past ecological harms.

The awful scale of these harms was vividly brought home during a visit to the museum in the seasonal settlement of Grytviken. There, I watched a short film on the industrial processing of whales. The historical footage was difficult to watch, not only because of the indifference to killing and butchering of these lifeforms but also because I realised that the explorers we now celebrate as heroes benefited from it and likely accepted its normality.

Later, my mood was sombre as we cruised into Stromness Bay and the site of two more abandoned whaling stations. However, my spirits were lifted by groups of macaroni penguins ‘porpoising’ by our boat as they sped toward their colony at a cliff’s base. The sight of these flamboyant and exuberant penguins, along with the awe-inspiring, tightly folded strata of the cliffs, starkly contrasted with the rusting whaling station. Instead of feeling sadness and regret, I marvelled at the hundreds of fur seals and their pups scattered among the ruins, along the shore and across the washlands of the Stromness River. A century ago, these seals were nearly wiped out by commercial sealing, yet here they were, back in huge numbers. I was overcome with a deep sense of gratitude. The era of industrial wildlife exploitation has passed, and I’m privileged to witness the capacity of nature to rebound.

In cruise ship narratives, the Stromness whaling station stands as the dramatic culmination of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s desperate 1,300-kilometre journey across the treacherous Southern Ocean in a small boat, accompanied by two fellow heroes, to rescue the crew of the Endurance, stranded on Elephant Island.

We reached Point Wild on this ice-covered, mountainous and shoreless island late the following afternoon. It was difficult to comprehend that 29 men had survived for four and a half months in this, the harshest of environments.

I had embarked on this journey with only a vague awareness of the Shackleton story. Yet, for many of my fellow passengers, it was a significant factor in their decision to join this expedition. Curious, I asked why they found the story so compelling. They spoke of Shackleton’s triumph of leadership against all odds and the profound power of hope, teamwork, endurance and determination to survive. As we explored the islands and bays of the Antarctic Peninsula, I began to see how similar themes were embodied in the Antarctic ecosystem – from penguin huddles sharing warmth and shelter against icy winds to orcas hunting collaboratively, and the Weddell seals enduring the bitter cold and darkness of the Antarctic winter. However, unlike human explorers, Antarctic wildlife is an integral part of the ecosystem, creating and sharing its life force. In this world, the meaning of heroism shifts from individual acts of bravery or exceptionalism to the interdependent and communal ways of survival that could be seen as heroic.

RECOVERY

One glorious morning, we set off in the Zodiacs to search for whales in Foyne Harbour. The landscape was breathtaking, with mini-icebergs scattered across the dark grey-blue sea, set against a backdrop of jagged peaks, snowfields and sharp blue sky. It wasn’t long before an earlier Zodiac radioed to say they had found some humpbacks. Three adults and a calf were resting in the still beauty, floating – or ‘logging,’ in whale-watching jargon – with occasional exhalations and rolls. Killing the engine, we floated together in peace, feeling, or at least wanting to feel, a sense of oneness with these majestic life forms and the bay.

Before returning to the ship, we visited the wreck of the Guvernøren, a Norwegian factory whaling ship that was intentionally grounded in 1915 to save the lives of its crew, who had accidentally set it on fire during a boisterous party to celebrate a successful whaling season. Until that point, I’d associated factory ships with the David and Goliath struggle between Greenpeace Zodiacs and Russian whalers. I hadn’t realised that factory ships were operating before the First World War.

With the advent of industrialised whaling, marked by faster boats and explosive harpoons, whalers shifted their focus from medium-sized species such as the humpback whale to the larger great whales – blue, sei and fin. Liberated from the pressures of hunting a century ago, humpback whale populations have shown remarkable recovery – we encountered more than 380 during our voyage. In Foyne Harbour it was I, not the whales, who was haunted by the memories of those crueller times.

I’m a rewilder. As an academic, I helped advance the science that underpins the movement’s practice. Now, as a co-founder of a start-up, I’m innovating with others at the intersection of rewilding, technology and finance to create digital financial assets able to ‘unlock’ investment in ecosystem recovery. Our development work is focused on Scotland, but with an international outlook. A trip to Antarctica seemed a good opportunity to ask whether our approach could work in a vastly different context.

Among the collection of PDFs I had brought with me for the trip was a recent scientific paper with the intriguing title: Whales in the Carbon Cycle: Can Recovery Remove Carbon Dioxide? I had been saving it for the perfect moment and cruising out of Foyne Harbour seemed to be just that. The science explored how whales facilitate carbon sequestration and aid ecosystem recovery. It was as beautiful and uplifting as the surrounding seascape.

Whales, as colossal consumers of krill and small fish, play an indispensable role in the so-called ‘biological carbon pump’. By consuming carbon-rich krill and fish, they not only store carbon in their bodies but also excrete most of it through their faeces. This process fertilises the growth of phytoplankton, which absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and forms the foundation of the marine food web. The carbon is either recycled within the marine food chain or sinks to the ocean floor with dead phytoplankton, faecal pellets and deceased animals, including whales. This effectively draws down carbon from the atmosphere, depositing it into the deep ocean, where it can be stored for centuries, or even millennia.

RE-THINKING

Human culture thrives on stories, yet in many countries, stories of a hopeful future are in short supply. A 2022 World Economic Forum report highlighted how negative perceptions of the future impact mental health, creating a vicious cycle that diminishes humanity’s capacity to address climate change. Antarctic tourism offers a unique opportunity to counter this narrative by infusing global culture with narratives of hope and recovery.

Although Antarctic cruise tourism presents risks associated with the introduction of alien plants, wildlife disturbance and anchor drag, these are being managed, and newer ships have auto-positioning systems that eliminate the need for anchors. My brief encounters with Antarctic wildlife suggested that it was largely unaffected by our presence, with some individuals even showing active curiosity. This prompts a crucial question: should the cruise industry simply bring passive observers, or should it actively participate in enhancing the ecosystem’s well-being?

Cruises could be marketed as voyages to a ‘sister world’ – a realm that showcases the power of nature to heal itself with human support. Onboard ‘edutainment’ and excursions could provide unique and immersive perspectives on ecological systems and planetary futures. IAATO could collaborate with scientific organisations to develop a coordinated onboard scientific monitoring programme and a post-cruise Antarctica ambassador programme with online resources, forums and campaigns to empower clients.

More radically, the industry could consider reimagining its vessels as functional species that, like whales, undertake seasonal migrations across the ACC. It could support the launch of Antarctica Recovery Credits – digital assets whose purchase is motivated by Antarctic stories, experiences and business sustainability commitments. These recovery credits would function analogously to phytoplankton, absorbing ‘atmospheric capital’ and converting it into financial resources that environmental groups can deploy, thereby creating a network of action to accelerate the recovery of the great whales, the ecosystem and the power of the biological carbon pump.

This integrated strategy could unite various entities within an organisational ecosystem, where the Antarctic Treaty Organization issues the recovery credits, the cruise industry motivates its clients and suppliers to buy them, the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research ensures that the credits finance and represent measurable ecosystem improvements, and environmental groups implement the conservation efforts the credits finance.

IAATO could spearhead a new ‘Antarctic Compact’, a collective pledge by tour operators, tourists, their suppliers and friends to champion and uphold the principles of ecosystem restoration, nature-positive tourism and the ongoing protection of Antarctica’s ecosystems. This compact could rejuvenate Antarctica’s cultural significance, enhance the region’s array of iconic wildlife and destinations, and forge meaningful connections between global citizens and Antarctic conservation and scientific endeavours. It has the potential to inspire a global environmental movement, accelerating transformative change towards a net-zero, nature-positive well-being economy and world. The industry has the potential to elevate the Antarctic Peninsula into a ‘national park of nations’ where curated experiences aboard cruise ships seed a hopeful narrative of recovery, energising an environmental movement that propels transformative changes toward a nature-positive economy and a world of well-being.

REWILDING

During the voyage, I didn’t experience the transformative moments some friends anticipated. But a polite ‘you first, no after you’ encounter with a gentoo penguin at a junction between her penguin highway and our tourist trail lingered in my mind. Reflecting on that moment when our vastly different worlds connected, I recalled the German concept of Umwelt – or ‘life spheres.’ This spurred me to explore how seabird studies, revolutionised by tracking technologies, are reshaping our understanding of the ‘Umwelten’ of different species – their unique intelligences and subjective realities shaped by sensory perceptions, bodies, behaviours and environments.

I realised that my approach to rewilding had been overly focused on the functional roles of species within ecosystems. I hadn’t fully appreciated the intricate layering of different intelligences, not necessarily conscious or intentional, that create our ecosystems. In the sister world of Antarctica, I discovered a new dimension of rewilding: one that offers exciting exploration into the mind-expanding complexity and elegance of our planet’s living systems.