Forty per cent of the global population live in the tropics – the zone that encompasses some of the world’s most underdeveloped regions and those most affected by climate change

By

The tropics are the geographical zone encompassing the regions around the equator, situated between the latitude lines of the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The tropics cover 36 per cent of the Earth’s land mass, and 40 per cent of the global population live within its regions, which include parts of North America, South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia.

More than 125 of the world’s countries and territories are at least partially located in the tropics. Their conservation and protection is vital, especially as by 2050 estimates suggest they will be home to more than half the world’s population while also coming under pressure from climate change, urbanisation, undernourishment, slum conditions, deforestation and logging.

Related articles

Climate and wildlife

With an average temperature of 25 to 28 degrees Celsius, the tropics broadly experience a two-season climate: the wet season and the dry season. They are largely hotter and wetter than the rest of the Earth, although the geographical zone called the tropics encompasses a wide range of different climates.

There are three main subtypes of tropical climate — the wet equatorial climate, the dry tropical climate and the alternately wet and dry tropical (monsoon) climates.

The wet equatorial climate mainly occurs within 5° north and south of the equator and features constant heat, high rainfall and humidity. Dry tropical climates, which largely exist between latitudes 15° and 30° north and south, have hot arid desert areas, making it almost impossible for rain-fed agriculture to take place. Monsoon climates occur across vast areas between 5° and 15° north and south including regions of South America, Central and West Africa, and Australia.

Levels of precipitation can vary greatly across regions. Some areas, such as parts of the Amazon Basin in South America, can receive almost three metres (nine feet) of rainfall each year, whereas the Sahara Desert only gets two centimetres to ten centimetres of rain (0.79 to 3.9 inches) per year.

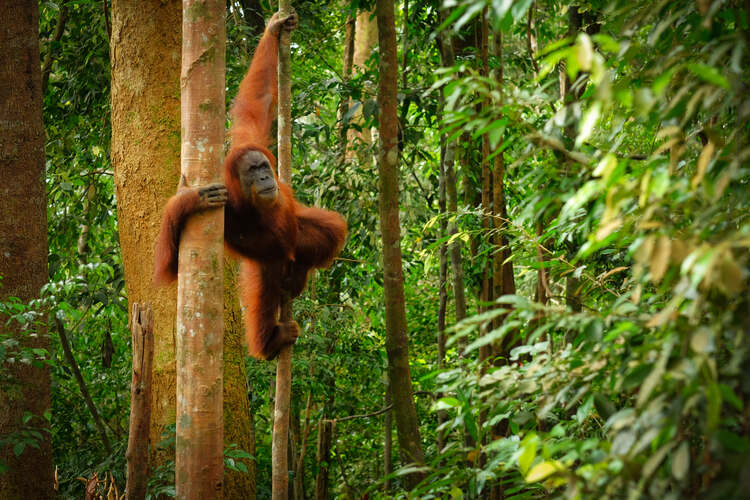

The tropics are home to vast numbers of tropical plants and animals, many of which are at risk of extinction. In the Wet Tropics region in Australia for example, almost 50 animal species, 200 plant species and three ecological communities are listed as threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. Species under threat include the mahogany glider, spotted tail quoll, northern bettong and the kuranda tree frog, with factors such as predation, habitat degradation and invasion of other species significantly impacting their survival.

Recovery plans have been developed for ten Wet Tropics species and ecological communities so far, allowing the most appropriate actions to be taken while carefully considering the context of the local economy, culture and environment.

Loss of primary forests

The tropics are home to some of the world’s largest and most important forested regions. However, the tropics lost 4.1m hectares of primary rainforest in 2022 — an area the size of Switzerland and an increase of around ten per cent on 2021 — according to figures from the World Resources Institute and the University of Maryland. The main causes were deforestation for agriculture, mining and cattle ranching. Deforestation impacts biodiversity and human communities, particularly Indigenous forest communities, some of which have been forced from their land by extractive industries.

In the past 21 years, 72 million hectares of primary forest have been lost across the world.

Reduced rainfall in the tropics

In March 2023, a study by researchers at the University of Leeds found that deforestation in the tropics was contributing to reduced rainfall.

By combining satellite data on deforestation in the Amazon, the Congo and Southeast Asia with rainfall data, researchers showed that rainfall reduction was linked to the loss of tree cover in the tropics over the last fourteen years. Loss of forest tree cover disrupts the process of evapotranspiration — the process by which leaf moisture is returned to the atmosphere to form rain clouds.

Reduced rainfall will have wide-ranging impacts across the world. For example, if the current rate of deforestation in the Congo continues, estimates suggest that rainfall could be reduced by between eight and twelve per cent, negatively impacting biodiversity, farming and the Congo forest’s viability, one of the world’s largest stores of carbon. A decline in rainfall also increases the risk of forest fires and reduces carbon sequestration potential (the process by which carbon is removed from the atmosphere and stored).

Agriculture and hydropower plants also suffer detrimental consequences from reduced rainfall, affecting forests and local communities.

The tropics are expanding

In 2020, a study published in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres found that the weather conditions of the tropics are expanding due to global warming. The study concluded that tropical expansion is primarily driven by ocean warming caused by climate change, as opposed to direct changes in the atmosphere. The largest shift in the tropics is occurring in the Southern Hemisphere, as it has more ocean surface area.

The consequences of tropical expansion include shifting storm paths, an increase in severe wildfires, and droughts in areas such as California and Australia.

Underdevelopment in the tropics

According to the UN, the tropics have the highest levels of human undernourishment and the highest proportion of urban populations living in slum conditions.

At the start of the 21st century, almost all tropical countries were underdeveloped — with only Hong Kong and Singapore ranking among the 30 countries classified as high-income by the World Bank.

A paper by Jeffrey Sachs, a researcher at the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests several reasons for the income gap between temperate zone countries (those with relatively moderate mean annual temperatures) and tropical regions. These included poor public health and weak agricultural technology in the tropics, as well as the difficulty of mobilising energy resources in tropical economies.

The productivity of major crops, (rice, wheat and maize) is also higher in temperate-zone regions than in the tropics, exacerbating the income gap between the two regions.

Challenging conditions in the tropics, including pests and parasites, water availability, soil formation and erosion, are all possible explanations for the region’s difficulty in producing crops. Supporting the tropics with agricultural technology that suits the demands of the climate is key when it comes to allowing the region to economically develop.

The tropics also face difficulties controlling malaria and other tropical diseases — exacerbated by the insufficient resources available for research and treatment. In Rio de Janerio, one doctor exists for every 370 people, and in the rest of Brazil, over half the population never see a doctor from birth to death.

While some tropical diseases, such as malaria, are well-known, others receive little attention. Take bilharzia, also known as schistosomiasis, a disease caused by parasitic worms that affects between 150-200 million people in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, and millions in mainland China. Estimates suggest that one strain of the disease reduced the working ability of patients from 15-18 per cent in mild cases, to 72-80 per cent in severe cases. With no effective cure, the disease continues to spread due to increased mobility of people and as a by-product of irrigation.