The fight to save the planet takes off — could solar geoengineering be a solution to rising temperatures?

By Jake Stones

Changing our behaviour towards the environment is increasingly being seen as a necessity, but making large-scale alterations to our lifestyles is taking time. When we break an 800,000-year constant and add 2,000 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) to our atmosphere in just 200 years, there are consequences. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that one such consequence will be global temperatures could rise by 4.8°C within this century.

While a solid, long-term fix is being developed, potentially radical methods are increasingly being considered. Solar geoengineering (SG) requires using fleets of aircraft to inject tonnes of sulphur into the stratosphere – between six and 30 miles into the sky. Despite sounding unorthodox, it’s a technique that has been on the minds of climate scientists for a while.

A team of researchers from Harvard University, Princeton University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has started to take the initiative and have published their findings in Nature Climate Change. The team open their paper optimistically, stating SG ‘has the potential to restore average surface temperatures by increasing planetary albedo.’

Stay connected with the Geographical newsletter!

In these turbulent times, we’re committed to telling expansive stories from across the globe, highlighting the everyday lives of normal but extraordinary people. Stay informed and engaged with Geographical.

Get Geographical’s latest news delivered straight to your inbox every Friday!

The major study, published earlier this year, outlines how the scientists used sophisticated weather models alongside their current programs on solar geoengineering to predict its impact on a planetary scale. The aim was to figure out what would happen if the Earth’s temperature cooled rapidly as a result of SG. To do this, the team used weather models to analyse the effects of reducing the intensity of the sun as though a stratospheric layer had been deployed via SG, the results produced ‘a similar radiative forcing to a solar constant reduction,’ the study claims.

When they programmed the models to predict halving our contribution to global heating, rather than offsetting the temperature rise entirely. This is starkly different to former studies on SG, which have calculated what removing all of impact from the last 200 years in one go. The team found that only 0.4 per cent of populated land would have exacerbated effects relating to precipitation and evaporation. This included western South America and South Africa.

Despite these issues, globally temperatures dropped. Importantly regions such as North America and Southeast Asia, areas that are set to be worst impacted by the climate crisis, even saw conditions improve. And when the team ran global storm cyclone simulations they saw a planet-wide improvement in conditions compared to unmoderated weather.

The thinking is that by injecting sulphur into the atmosphere, it will form a reflective layer, dimming the sun’s rays and cooling the planet’s temperature. This belief isn’t entirely abstract. In 1991, following the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, 17 megatons of sulphur dioxide entered the stratosphere. This cooled the Earth’s average temperature by 0.5°C. Crucially, the last time our global temperature was this low was just before the invention of the steam engine.

Approximately two years after the Pinatubo eruption, the effects wore off. Once the sulphur had dissipated, so too did its reflective force, and temperatures rose back to pre-eruption levels. Although this shows solar geoengineering to be a means of cooling the planet temporarily, it’s not without its theoretical risks.

Dimming the sun’s rays has been shown to impact plant life, plants that currently offset some 25 per cent of humanity’s CO2. It would also put food supplies under strain. Further, as solar geoengineering doesn’t negate CO2 emissions, the process of oceanic acidification continues. The oceans absorb one-third of our CO2, which raises its acidity levels. Over the last 200 years, the acidity of the oceans has increased by 26 per cent. This leads to the breakdown of calcium carbonate, which destroys corals and damages shell-based life.

Also endangered by oceanic acidification are the water-based, microscopic organisms known as phytoplankton. Although tiny in size, these organisms account for half of the amount of oxygen we breathe. They also produce the chemical dimethylsulphide, a crucial part of the nuclei of water vapour, allowing it to form into raindrops. With less phytoplankton there would be less dimethylsulphide, which means less rain and more drought.

While the study did bring up some positive findings, there have been criticisms. Geophysics professor Alan Robock, a researcher at Rutgers University, New Jersey, questions the using SG on the basis of this study, stating ‘I don’t think it is correct to imply that geoengineering is a good or safe idea.’ His primary criticism focuses on the methodology of the study, noting that using climate models isn’t the same as simulating the release of volcanic aerosols such as sulphur dioxide. ‘There is no way to do what they modelled,’ says Robock, highlighting ‘we cannot turn down the sun.’

Harvard professor, David Keith, one of the study’s authors, admits that solar geoengineering is still in its infancy and that ‘deployment would be ridiculous’ based on this study. More research needs to be conducted, including on the means in which SG would be deployed.

The study also falls victim to another, slightly more pressing concern. Rather than accounting for future CO2 emissions, the models only analysed current levels. With humanity’s population set to rise to around ten billion people by 2050, it’s more than likely that unless we as a species change, CO2 levels will increase. According to NASA, over the last 800,000 years the highest proportion of CO2 in the atmosphere was at around 280 parts per million (ppm) all the way up until the industrial revolution. In 1958 the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii began monitoring the atmosphere, giving a first reading of 320ppm. Then in 2013, we surpassed 400ppm. And finally, in May of this year, that same observatory has recorded 415ppm.

To give an indication of time, the IPCC’s AR5 Synthesis Report cites studies which indicate if we’re to keep global temperature rise below the 1.5C target, then we need to remain below 430ppm.

These issues aren’t ignored by the team, who themselves call for more research to be done; Professor Keith opposes the idea of implementing solar geoengineering right now. Instead, he highlights that this is just an initial phase of the research that should be ongoing, urging that ‘we need to get beyond a few researchers just doing this as a hobby.’

Keith argues that his generation isn’t going to be the one burdened with making the eventual decisions on utilising these methods. ‘It’s going to be our kids who make a serious decision about solar geoengineering,’ he says, suggesting that research such as this is being conducted in order to make that future decision-making easier.

Subscribe to our monthly print magazine!

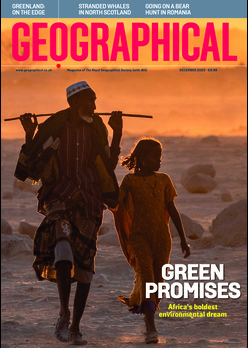

Subscribe to Geographical today for just £38 a year. Our monthly print magazine is packed full of cutting-edge stories and stunning photography, perfect for anyone fascinated by the world, its landscapes, people and cultures. From climate change and the environment, to scientific developments and global health, we cover a huge range of topics that span the globe. Plus, every issue includes book recommendations, infographics, maps and more!