Once thriving centres of life, Morocco’s oases are drying up due to high temperatures, prolonged droughts and unsustainable water management

Words and photographs by Vincenzo Montefinese

Morocco is paying a high price for the desertification process that is sweeping the Sahel region. Its oases are rapidly disappearing. Dehydrated, ravaged by fires and progressively abandoned, they are severely threatened by both climatic phenomena and human activities.

Covering 15 per cent of the country and home to about two million people, the oases have lost two-thirds of their surface area over the past century, according to Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture data. The number of date palms, a vital resource for the economy and the oasis ecosystems, has plummeted from 15 million to six million.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

The impact of climate change is particularly severe in the Draa Valley, in the southeast of the country, where the Draa River – the longest in Morocco, originating in the peaks of the High Atlas – which once sustained the region, flows less and less frequently. The construction of dams and the intensive use of water resources for agricultural or industrial purposes have further worsened the situation, jeopardising the survival of the oases.

Saif, 49, in Tinzouline, Draa Valley, protects dates with a green net, trying to shield them from insect attacks and diseases, which have intensified in recent years due to drought and high temperatures.

The landscape has changed dramatically in recent years: the bridges that once spanned the Draa River now connect only the banks of a dry riverbed, while vast green areas have been transformed into arid scrub. The decrease in rainfall and rising temperatures have disrupted the water balance of the oases.

The khattara system – ancient underground tunnels that for centuries channelled water from aquifers to the fields – has become insufficient in the face of increasing drought. The need to dig deeper wells has led to higher soil salinity, rendering much agricultural land infertile.

A woman walks near the bed of the Draa River, now devoid of water. The river, the longest in Morocco, originates from the Dadès and Imini rivers in the High Atlas Mountains and flows for 1,100 kilometres to the Sahara dunes, then continues towards the Atlantic near Cap Draa. Along its course, the Draa passes through mountains, palm groves and Berber villages, whose survival depends on water for agriculture.

Without regular rainfall, there’s a growing risk that desertification will completely consume the few remaining green areas. Local communities are striving to adapt as best they can.

Some farmers are experimenting with innovative techniques, such as rainwater harvesting and the use of natural materials to create micro-irrigation systems. In an effort to sustain the local economy, some have sought to develop tourism in the oases, converting ancient kasbahs and caravanserais into guest accommodation. However, without sustainable water resource management, tourism risks making the problem worse.

Salim El Kabir, 42, adjusts the solar panel that powers the pump for extracting water from the well used for irrigating date palm groves near the Draa River. The increasing drought has driven farmers in the Draa River basin to dig more wells, often illegally, to gain access to groundwater.

On closer inspection, all these local solutions aren’t enough to halt the advance of the desert and require more structured support from central authorities. In response to the crisis, the government in Rabat has launched a series of projects for sustainable water resource management. Among them, the ‘green plan’ includes reforestation of some desert areas and the construction of new infrastructure for water collection and treatment. But the impact of these initiatives is still limited and prone to bureaucratic delays and a lack of funds.

Touda Ihssissn, 35, and her children Maryam, 15; Fatima, 13; and Rachid, 11, are nomads from the Amazigh tribe who live among the mountains of the High Atlas, sleeping in tents made of camel wool and goat hair. Over the past twenty years, due to drought and increasing desertification, food for raising animals has become increasingly scarce, and many Ait Atta families have given up their nomadic lifestyle to move to urban areas in search of work.

International organisations such as the World Bank and the UN have launched support programmes to strengthen the resilience of the oases. These initiatives include the introduction of drought-resistant crops and the promotion of sustainable farming practices that reduce dependence on water resources. But such initiatives are having little impact on the growing problem.

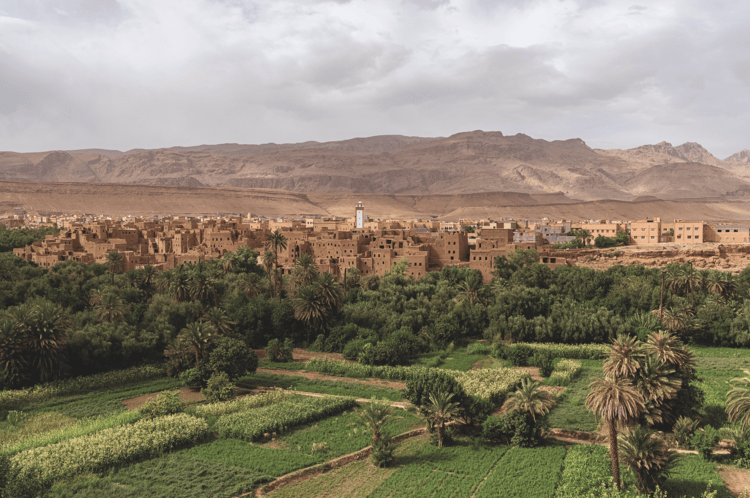

A panoramic view of the Tinerhir oasis, which stretches for about 30 kilometres along the Todra River. Located in southeastern Morocco, the oasis is known for its lush palm groves and ancient kasbahs made of mud bricks.

At risk is not only the natural ecosystems, but also the cultural heritage of the communities living in these regions. The Ait Atta, Amazigh tribes who live between the High Atlas and Jbel Saghro, are abandoning their traditional nomadic, pastoral lifestyle due to frequent droughts, which make it increasingly difficult to find forage for livestock. The drastic decline of natural resources forces them to settle in urban areas, creating new pressures, widening the gap between rural and urban areas, and accelerating the disappearance of the traditions and cultural heritage of the Ait Atta.

Ahmed El Mandori, 72, opens the canal that allows him to receive water from the Khettara irrigation system, twice a week, to irrigate date palm fields.

The gradual abandonment of cultivated land has made way for fires, which devastate vast areas of date palms and agricultural fields, further promoting the advance of

the desert. Recently, the southeast region of Morocco has been hit by a series of fires that have further compromised the already fragile landscape. The flames, fuelled by drought and hot winds from the Sahara, have destroyed hectares of green areas, worsening an already critical ecological and economic situation.

Zaid Oukhazaid, 56, a member of the Imazighen tribe, carries grass that he has collected to feed his livestock in Jbel Saghro, a mountain range that forms part of the Anti-Atlas. Recent drought has caused a drastic reduction in food availability for the tribe’s animals

An abandoned well in Tinzouline, Draa Valley, now completely dry due to the drought, stands in the middle of a date palm grove.

A man purchases bales of hay for his animals on the edge of the Erg Chebbi desert, where drought has made it increasingly difficult to find pastures.

Issam Moha, 46, a nomad belonging to the Afourer community, descends into a well to check the water level among the mountains of Jbel Saghro. The precariousness of the water supply makes each visit to the well a moment of great anxiety and anticipation.

Affected families have had to abandon their homes, seeking refuge in larger cities. This scenario of climate crisis and forced migration raises questions about the future of the oases and Morocco’s ability to face such a challenge.

The loss of biodiversity and the decline of traditional communities pose a risk to the entire country, which is witnessing the crumbling of one of its most precious treasures.