Image: Arthimedes /Shutterstock

Mark Rowe reports on one the most significant demographic shifts facing the world

FACTS

In 1950, Africa accounted for 5% of world population (227,549,258)

By 2050, it will account for 25% (2.5 billion)

And in 2100, it will be 40% (4.2 billion)

Africa’s median age is 18.6. India’s is 28; for both China and the USA, it’s 38

Nigeria will be the world’s third most populous country by 2050

Does size matter? When it comes to Africa, we’re starting to find out. Population growth on the world’s poorest continent is outpacing that of the rest of the world. In 1950, when the pan-African population was first calculated, the Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat came up with the figure of 227,549,258, accounting for just five per cent of global population. A hundred years later, by 2050, this will have risen to 2.5 billion, or 25 per cent, and is projected to approach 40 per cent by the end of the century. While population growth in other regions has slowed, Africa’s has increased by 2.42 per cent per year for the past 30 years.

Of the eight countries expected to account for more than half of global population growth by 2050, five are in Africa: Tanzania, Ethiopia, Egypt, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Nigeria. Nigeria is forecast to become the world’s third-most populous country, larger than the USA, by that year.

THE GOOD NEWS: FEWER DEATHS

The demographic shift is driven by three factors – child mortality, female education and economic development – which interact but also pull in different directions, according to Steve Wiggins, a research fellow at the Overseas Development Institute. ‘It comes down to basic demographic facts,’ he says. ‘The death rate comes down first, in relation to infant and child mortality. It’s good news. You only have to go back to the 1980s to see one in five children were dying before their fifth birthday. Parents knew that if they had five kids, they might get away with four and be doing well. You just expected tragedy to strike regularly.’

AN EXCEPTION TO THE RULE

One universal demographic truth is that the more educated a nation becomes – particularly girls and women – the smaller the family size. Yet Nigeria appears to be an exception to this rule, where the birth rate has declined only by fractions of a percentage point over the past two decades and remains around five. To some extent, this may be the same baby boomer phenomenon witnessed in Europe and the USA in the 1960s, whereby child mortality rates fell before translating into a desire for fewer children. A quirk in state funding is influential too – national oil revenue is allocated to each of Nigeria’s 36 states based on population size. Furthermore, says John Bongaarts of the Population Council, the dynamic among the country’s three main tribal groups means that no-one wants to see their ratio of the population shrink. So the system works against population control.

According to John Bongaarts, a distinguished scholar at the Population Council, fertility has been high in Africa for a long time. ‘It was six to seven children up to 1990. Then death rates went down, but birth rates stayed high.’

The mean infant mortality rate across Africa reduced from 88 per 1,000 live births in the year 2000 to 41.5 per 1,000 in 2023 – still horribly high (in developed nations such as Finland or Japan, the rate ranges from 1.5 to 2 per 1,000) – but forecast to drop further to 13 per 1,000 by the end of the century, according to the UN. Current rates include 85 per 1,000 in Somalia and Chad, and 92 per 1,000 in the Central African Republic.

BETTER HEALTHCARE

Infant and mother survival rates turned for the better in large part because of projects begun in Malawi around the year 2000 and imitated elsewhere. Nurses and paramedics were deployed in villages to deliver vaccines and public health. According to the World Health Organisation, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) has decreased from 708 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 531 per 100,000 in 2020, when Africa still accounted for 69 per cent of global maternal deaths. Compared to 2017, in 2020, the MMR increased in 17 countries and decreased in 30. In Sierra Leone, the MMR dropped by nearly 60 per cent (443 deaths per 100,000 live births); Nigeria’s MMR (917 per 100,000 in 2017), rose by nearly 14 per cent to 1,047 per 100,000.

And the effects of better healthcare are being felt beyond early years, with the UN projecting that life expectancy on the continent will rise to more than 70 years by 2060, although not without regional variations.

FERTILITY RATES: THE NUANCED VIEW

The next key to demographic change is fertility – a critical component, because those countries set to maintain the highest fertility rates will face some of the most challenging aspects of booming population growth. Here, too, there have been changes. A similarly holistic approach to that applied in Malawi was applied to birth control in some regions. ‘Pregnant women no longer went to a health centre to see a man in a white coat,’ says

Wiggins. ‘Instead, local nurses asked whether or not they wanted to have more children. The secret to bringing down fertility rates isn’t handing out condoms at traffic lights; it’s female paramedics turning up on doorsteps and speaking the local language.’

Eight of the ten countries that witnessed the largest increase in the use of modern contraception methods bertween 1990 and 2021 were in sub-Saharan Africa: Ethiopia, Eswatini, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

There’s still work to do, however: in sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of women who have their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods (a key Sustainable Development Goal) remains among the lowest in the world at 56 per cent. And, despite decreases in the rate of unintended pregnancy, nearly one in ten women in sub-Saharan Africa and northern Africa continues to experience an unintended pregnancy every year.

The truth is, the picture is extremely varied. Generalisations are a fool’s endeavour. To make the point, raw UN statistics show that rural populations in North Africa are growing ever more slowly; meanwhile, rural populations in sub-Saharan Africa grow ever more rapidly. As Wiggins puts it: ‘Few people would conflate the Nordic countries with the Balkans, but treating all of Africa as one bundle is common. Those who think themselves wise by talking of sub-Saharan Africa congratulate themselves on having hived off North Africa, then fall even faster in the trap of seeing the rest of the continent as one big mass.’

Across Africa, says Wiggins, the fertility rate is ‘incredibly uneven, but the trend everywhere is down’. For some time, Botswana has been hitting the replacement level of 2.1 children, but in Niger, where a median age of 14.5 makes it the youngest country in the world, the latest figure is 6.7.

URBANISATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

While every country has a unique population dynamic, Africa’s wider picture is one of huge pressure triggered by lightning-fast change, most evident in urbanisation. Africa’s urban population is expected to triple in the next 50 years according to the UN, which has set the goal of ensuring everyone has access to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services by 2030. Yet a study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine found 47 per cent of people in urban sub-Saharan Africa still live in slum-like housing.

This means that ‘population growth in and of itself is not what drives whether or not we achieve the Sustainable Development Goals,’ says Thoai Ngo, VP of social and behavioural scientific research at the Population Council. ‘Population dynamics such as increasing urbanisation and migration are reshaping where people live – and why – and impacting the resiliency of communities. Economic, health and social inequities are multi-faceted and mutually reinforcing.’

Some parts of Africa have grown at the fastest rates in the world, says Wiggins. ‘In the 1980s, Kenya was growing at four per cent a year, so the population was doubling every 18 years. That kind of pace is hard to get your head around. What were tiny villages 40 years ago are now bustling and urbanised. Vast bush areas get rapidly filled in. Significant areas of over-population, precarious-looking powerlines and urbanisation can look unsightly.’

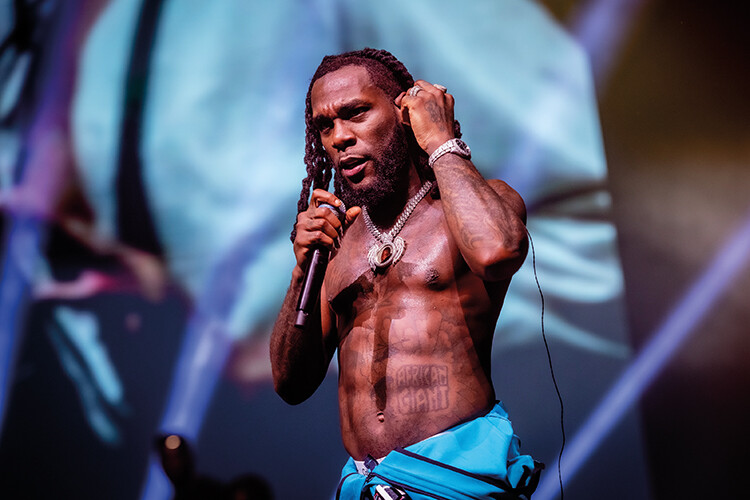

A GLOBAL VOICE

For some time, Afrobeat has been a motif of African music and culture, its rhythms, jazz and funk enjoyed by hundreds of millions worldwide. As African populations grow, can we expect even more cultural influence to spread across the globe, projecting, selling and marketing African cultures internationally? The number of African nominees for the Grammy awards has grown in recent years; interest in African apparel and fabric is reflected in fashion weeks held in cities across the continent; Nollywood, the Nigerian film sector, produces about 2,500 films made each year and is the world’s number two film industry.

The film and audiovisual sectors, worth US$5 billion and employing five million people, remain largely untapped, with a potential value of US$20 billion, according to the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers.

‘When poverty, fertility and mortality indicators move in the right direction, it gives people time and space to be creative – they don’t have to focus on basic needs,’ says Thoai Ngo of the Population Council. ‘The world can benefit from more richness from African culture. People are always thirsty for something different.’

Such trends bring simple truths. ‘Very rapid population growth has very negative effects. There’s little to be gained from high trends,’ says Bongaarts. ‘If a population triples, everything needs to be tripled – electricity plants, schools, food, healthcare – and that’s just to stay still. There’s no capital to invest; you’re just hanging on.

‘You have very large numbers of young people trying to get into the labour force, unemployment is massive so young people end up in crime or attracted to the rebel groups that are roaming about the Sahel.’

Rapid growth puts pressure on the natural world, too, from encroaching on wild places to disrupting ecosystems. ‘Adding three billion people to a continent has environmental consequences,’ says Bongaarts. ‘Tripling the population of a desert country such as Niger makes no sense – it puts huge pressure on resources. Environmental damage often arises from the economic processes that lead to higher standards of living,’ said a spokesperson for the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, ‘especially when the full social and environmental costs, such as damage from pollution, are not factored into decisions about resource extraction, production and consumption.’

THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND

How Africa’s demographic transition plays out on a regional scale will depend on how well different nations harness what’s known as the demographic dividend. This concept occurs when a period of high fertility, as experienced by most African nations in the last decades, is followed by a reduction in birth rates and mortality. This changes the age structure of a country’s population and means that the size of the labour force increases relative to both young and old dependents, leading in turn to better economic growth and lower levels of poverty. ‘If you slow population growth, then you can save money that can be invested in other stuff, such as new roads, housing and schools,’ says Bongaarts.

‘The demographic transition profoundly transforms the age distribution of a population,’ says the UN spokesperson, ‘lower levels of fertility and smaller cohorts of dependent children and youth create a window of opportunity.’

PREDICTIONS AND MYTHS

While African fertility rates have historically been higher than the global average, the picture is extremely nuanced. Steven Wiggins, of the Overseas Development Institute, has spent many years studying what he calls ‘the alleged high fertility of Africa, seen by some as a kind of cultural constant applying across the continent’, and found it to be myth. ‘Some African nations have much lower fertility than might be predicted, given their levels of economic development and female education,’ he says. ‘The point we make is simply, there’s no African norm that predicts higher rates of fertility than in other regions.’

Lesotho’s predicted fertility rate of 4.74 translates in reality to 2.85; Sierra Leone’s true figure is 4.31 versus 5.36. The explanation for the difference between expected and actual rates for Lesotho is ‘male emigration to South Africa, combined with women at home having then to run the household, farm and anything else unaided,’ says Wiggins. ‘South African norms, where decent jobs go to those with qualifications, may convince parents that fewer children with more invested in their care and education is better than many children.’ In Sierra Leone, Thoai Ngo of the Population Council credits David Sengeh, the Harvard-educated chief minister, for driving technology-based education and societal reforms.

Some African countries are much more likely to benefit from this dividend than others. Rwanda and Botswana appear set to benefit first, according to Bongaarts. ‘Both have taken significant steps to lower fertility and invest in education. It’s going to be messy in many places, but there will be many countries where things are going to be okay. I’m more concerned about trends in Nigeria and DRC.’ Birth rates in the latter two countries are at 5.3 and 6.2 respectively.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) is keen to emphasise the fact that current demographic trends present a huge opportunity for many African nations, especially if education is baked into structural reforms. ‘With a rapidly growing population, increased urbanisation and what is soon to be the world’s largest workforce, Africa has an opportunity to transform into a global economic powerhouse,’ declared a recent paper issued by the AfDB. Development can happen organically, but the UN spokesperson points out that ‘reaping the maximum potential benefit of this demographic dividend requires sufficient improvements in education, health and gender equality, and in access to productive employment and decent work.’

Government competence and oversight are essential, says Wiggins. ‘The huge challenge is to keep a steady hand on the tiller, to keep the social fabric together. Combine economic development with a social fabric and a lot will happen. You get incipient urbanisation, services start up, schools start to appear. Economic opportunities get created for near-destitute pastoralists, whether it’s new markets for food or jobs in construction. This is happening all over Africa – there is a dynamism happening at rural levels.

‘But it’s a two-sided story. People want to achieve things off their own bat, but the road to the developing village, schools, healthcare centres, doesn’t come out of nowhere. You need entrepreneurship combined with sound government investment. Give people the infrastructure and services and don’t muck around when they start doing stuff with it.’

EDUCATION, EDUCATION, EDUCATION

The demographic dividend gets wasted if measures are applied half-heartedly, warns Bongaarts. ‘It’s about more than simply putting kids in schools. It’s meaningless if you have poor schools and few teachers – it won’t look much like a dividend if you just have lots of young people.’

According to the AfDB, 500 million African adolescents can barely read or write; fewer than half of young people will find formal jobs in the coming decades. The World Bank reports that sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of education exclusion of all developing world regions. More than one-fifth of all primary-age children are out of school, as are 60 per cent of those aged 15–17. Such a level of disengagement can stall economic progress and be detrimental to population health, ultimately destabilising social systems, warns Ngo, who stresses the need to target gender barriers and change cultural norms. ‘In countries experiencing the “youth bulge”, governments and the private sector must work together quickly and at scale,’ he says. ‘Young people must be educated, must have healthcare and reproductive freedom, and access to good jobs. Women and girls must have full social and economic participation. Our ability to avoid catastrophic effects from climate disasters is contingent on harnessing the demographic developments that are shaping African cities and communities.’

Africa’s median age is 18.6 years – India’s is 28; China and the USA both stand at 38 – and Ngo describes the ‘exciting potential for a continent to invest in this generation’ – but so far, he argues, education hasn’t realised the potential to mobilise and up-skill the human capital this generation represents.

So much comes down to education for girls. Girls are now much more likely to start primary school in nations in sub-Saharan Africa, but their likelihood of completing it often remains low. A World Labour Organisation report calculates that an increase in women’s schooling – from half of the schooling men receive to equal levels – is associated with a fertility rate decline from six to two. ‘Girls in secondary school is an incredibly powerful factor in women’s fertility. Every additional year of female education lowers fertility. That’s true in every country, rich or poor,’ says Bongaarts.

NEW GLOBAL POWERS?

Will larger populations translate into greater political clout on the global stage? If numbers talk, individual nations and the wider continent could be in a position to frame policy around climate change, debt and historical colonial legacies, and properly exploit resources that include minerals essential for the clean-energy transition, such as cobalt, manganese, graphite, copper and tin. This could be wishful thinking, according to Bongaarts. ‘Population has relatively little relation to its political power – just look at France and the UK, which have seats at the UN Security Council. India has a population of more than one billion but has only recently gained influence as it has developed economically.’

Wiggins too is unsure, pointing to the lack of industrialisation across the continent. ‘Political clout usually goes with military power arising from closeness to trade routes and control of minerals, oil and gas.’ Few countries in Africa rank highly on these factors, he points out, with exceptions such as Egypt, thanks to its fossil fuels and the Suez Canal. Could things change? ‘It’s hard to imagine that the more populous countries of Africa will not soon demand to be part of the G20 on their own account, not proxied by the African Union.’

While demographic change happens rapidly, tangible benefits may materialise more slowly. ‘The real fruits will only be seen in coming decades,’ says Wiggins. ‘It’s a hard message for a leader to give to their population: patience and sacrifice, work hard for 20 years and your children, but not you, will see amazing benefits.’

Some nations may be left behind, warns the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. ‘Countries with relatively low per capita incomes and high levels of fertility will need to achieve robust and sustained economic growth if they are to meet the goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,’ says the spokesperson.

Nations are likely to develop their own momentum, adds Wiggins. ‘There’s now a generation of smart young Africans, aged 20–30, who have grown up with good nutrition and a decent university education. They rarely had that opportunity in the 1980s. They give me tremendous hope. They are not going to sit there and let Europeans dictate things. They want to stay in Africa and make a difference.’