As the conflict in Ukraine rages on, vulnerable communities caught in crossfire are struggling to access basic health services

Photographs by Sean Sutton

Stepping through the doors of City Hospital No. 9, says Rosemary Loughlin, was like walking into a museum.

The 60-year-old nurse from Grimsby in the UK had arrived in the southeastern city of Zaporizhzhia (population 710,000) in early August. It had been a long and daunting journey – the only time she’d ever travelled on her own and this was her first experience of a Ukrainian healthcare facility.

Related reads:

‘Everything was so antiquated, the surgical table, the instrumentation… In nearly 40 years of work, I’ve never seen equipment like that.’

As a theatre nurse in the UK, Loughlin is used to 14-hour days spent on her feet, assisting with operations to fix broken bones and crumbling joints. ‘It’s long, hard work,’ she says, ‘but everything you need is on tap.’

Shortly after arriving in Ukraine, however, Loughlin recalls she spent a Monday morning cutting and bundling up fabric to make surgical swabs. ‘We quickly realised just how limited the resources were for even the most basic things.’

Since gaining independence in 1991, Ukraine’s healthcare system, a legacy of the Soviet Union, has been plagued by underfunding and the need for structural reform.

The number of doctors and nurses in the country has been falling since 2016 – in 2022, Ukraine had half the average number of nurses in the EU – and, in the east of the country, at war since 2014, healthcare staff had been struggling to meet the growing needs of patients long before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Then, on 24 February 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion.

Psychologist Tatiana Yevstratova reassures Hanna at a mobile clinic in Dymitzvika village, Kharkiv. An estimated 54 per cent of Ukrainians have post-traumatic stress disorder, another 21 per cent suffer from severe anxiety. Image: Sean Sutton

In the northwest of Zaporizhzhia, on the banks of the Dnipro River, Ukraine’s largest hydroelectric power plant is in a critical condition. The dam, whose reservoir is used to cool Europe’s largest nuclear facility (the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant) has repeatedly been targeted by Russian attacks, and much of the city is now without electricity.

Nearby, at No. 9, back-up generators mostly keep the power on, but the air conditioning in the glass-walled hospital building fails daily. During the summer, as temperatures in the operating theatre climbed to 35°C, Loughlin often found herself working alone with the surgeon. Her shifts were shorter, but every task took longer to complete.

‘It took 40 minutes one day to drill a hole through a plate. That should take seconds, but the drills are so blunt, and it was a young patient so the bone was hard.’

Loughlin is one of 580 UK-based healthcare workers (42 per cent of whom are nurses) who volunteer with humanitarian NGO UK-Med on the frontlines of health crises around the world. Born out of the NHS in the 1980s, at a time when paramedic training was still in its infancy, the Manchester-based charity was initially formed to support ambulances with critically ill or injured patients.

In 1988, a small team travelled to Armenia in the wake of the devastating Spitak earthquake, which killed an estimated 25,000 people and left hundreds of thousands homeless.

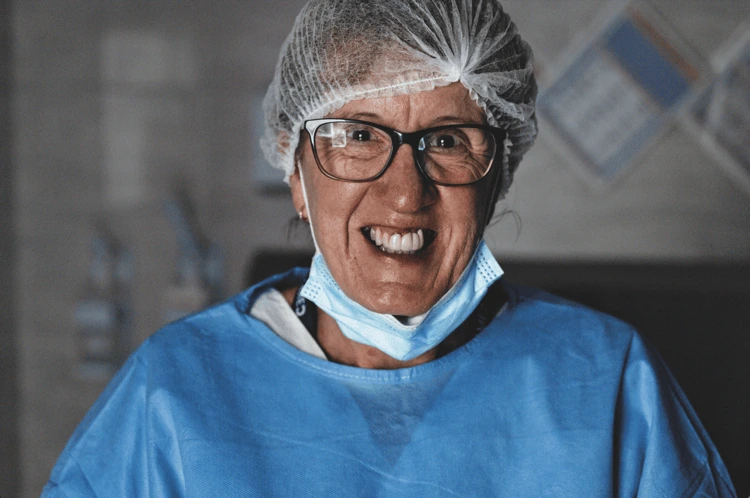

British nurse Rosemary Loughlin volunteered to work in Ukraine’s desperately over-stretched surgery wards. Image: Sean Sutton

Since then, UK-Med has treated communities in Cape Verde (after the 1995 Pico volcanic eruption triggered an outbreak of cholera), casualties of the 1992–96 siege of Sarajevo, and Ebola patients in Sierra Leone. It was one of the first NGOs to enter Ukraine after the Russian invasion, where it has been on the ground since 4 March 2022.

The war in Ukraine has had devastating consequences for the country’s already beleaguered healthcare system. Mass displacement, the destruction of infrastructure and supply chains, and a large fall in household income have left millions vulnerable to previously uncommon illnesses such as cholera and existing high-burden diseases (cardiovascular diseases, cancers and diabetes, as well as some of the highest rates of HIV and tuberculosis in Europe).

In villages close to the front lines, most of the young people have left. Those who remain are isolated, with little access to healthcare. Image: Sean Sutton

A staggering 81 per cent of households are struggling to afford essential medication, particularly for heart conditions, high blood pressure and pain relief.

In rural areas, an ageing healthcare workforce is now stretched to its limits, with just seven per cent of the country’s nurses serving 30 per cent of its population.

As of 1 December 2024, the WHO has also recorded 2,165 attacks on healthcare services – 1,823 of which have affected hospitals and other facilities – resulting in the deaths of 197 healthcare workers and patients, and injuries to another 680.

‘We do the complicated operations here,’ says anaesthesiologist Nidal at the hospital in Zaporizhzhia. ‘We deal with all sorts of injuries, but landmine explosions and car crashes are common’. Image: Sean Sutton

An average of 200 ambulances per year have been damaged or destroyed since February 2022. Healthcare workers are facing burnout and the country is experiencing a growing mental health crisis. ‘There has been no respite for civilians in Ukraine,’ said Joyce Msuya, the UN’s acting under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs and emergency relief coordinator, following a strike on Ukraine’s largest children’s hospital on 8 July last year.

Today, nearly three years since the start of the war, UK-Med continues to provide surgical support for Ukrainian medics in hospitals across eastern Ukraine, where there is a large demand for specialist surgery for wounds and limb and facial reconstruction.

Mobile health clinics – ‘GPs on wheels’ – are deployed in remote and rural areas, where access to primary and mental health care is scant.

Loughlin first heard about UK-Med through a colleague who had travelled with the charity to Gaza earlier in 2024. ‘I’d always wanted to do… something,’ she says. ‘When my friend, who’s 70, went, I thought: “Well if she can do it, why can’t I?”’ After a month of e-training modules, a rigorous medical exam, and interviews to confirm her physical and mental suitability for the role, she was offered an eight-week contract.

‘They said they were desperate for me,’ she adds. ‘There’s a lot of trauma, whether it be amputations or removing shrapnel. Injuries aren’t always a direct result of the war, some are caused by the state of the pavements. People are stressed, so accidents are common. We get a lot of elderly patients with fractured neck of femur [a broken hip].’

Many of UK-Med’s patients are internally displaced people who have been forced to flee their own homes and battered villages. Image: Sean Sutton

Despite the proximity to the front lines, the residents of Zaporizhzhia try to carry on as best they can. On days off, Loughlin and her colleagues – also volunteers with UK-Med – pick plums to make into jam and ice cream. ‘One time,’ says Loughlin, ‘while I was at the park, a bomb went off a mile away. The ground shuddered, but nobody reacted. It was a normal day.’

She adds that while her sons, 23 and 25, were proud and supportive of her decision to go to Ukraine, they initially thought she’d gone a bit mad. ‘But there wasn’t a single day when I didn’t feel safe; UK-Med made sure of that. The most frightening thing was having to share and re-use instruments and keep everything clean and sterile.’

Women wait to see the doctor at the mobile clinic in Korbyni Ivani village, 12 kilometres from the front line. ‘We see missiles flying overhead, heading for Kharkiv every single day,’ says Katerina (in the blue dress). ‘We are so happy UK Med is here’. Image: Sean Sutton

Loughlin wouldn’t hesitate to return to Zaporizhzhia. ‘I found it the most enriching, satisfying experience ever. Yes, they have very limited resources, but they have the most resilient, remarkable staff. You feel that what you are doing is so worthwhile, and so desperately needed.’ At the moment, however, the next few months look uncertain for UK-Med’s ongoing work in Ukraine.

CEO David Wightwick says that as Ukraine has faded from media headlines, public and political awareness has decreased. Current funding runs out in May and with nothing else in the pipeline, and general concerns about what the US election results might mean for Ukraine aid, the team is concerned about the future.