The charity working with the young women forced into prostitution in India’s holiest city

Words and photographs by

A ghostly dawn mist hovers above the glassy surface of the river. At the foot of the steps, known as ghats, that line the riverbank, a group of people – women in searing orange and red saris, men in white vests – lower themselves cautiously into the water. Once they are waist deep, they pause, brace themselves against the chill of the winter morning and then, as one, immerse themselves completely. They repeat the process several times, the waters of the holy River Ganges running over them, symbolically washing away all that is bad. After some minutes, the pilgrims clamber, shivering, back up the steps to dry off and as they do so, the rising sun illuminates them in a soft orange glow. Behind them sits the ancient city of Varanasi, bathed in morning light.

One of the holiest places for Hindus, Varanasi attracts tens of thousands of Hindu devotees every year. By bathing in the Ganges, pilgrims believe that a lifetime of sin will be erased. Legend has it that Varanasi in northern India was founded thousands of years ago by the Hindu god Lord Shiva. It was, so the story goes, the first place where the divine light of Shiva pierced primordial darkness,. It’s for this reason that Varanasi is also known as Kashi, or the City of Light.

But, where there is light, there is also darkness.

‘I’m from a small village not far from Varanasi. My father was an agricultural labourer, and we never had much money,’ Deeksha (not her real name) told me in a voice that was little more than a whisper. ‘One afternoon, my mother sent me out on an errand. On the way home, I met one of my older cousins and an auntie. My cousin offered me some prasad [a food item given as an offering in Hindu temples], but after I ate it, I felt giddy. My cousin told me that if I said anything to anyone, then they would kill me with a knife. I don’t recall everything that happened afterwards, but I was put on a train with my cousin and taken to Kolkata. When we got there, my cousin locked me in a tiny, dark room where he beat me and raped me many times.’

Deeksha sat on a small wooden stool as she told me her story. Aside from some worn blankets and a couple of paper-thin mattresses, the stool was the only piece of furniture I could see in the two-room apartment she shared with her mother and young son. Like all the buildings in the suburb of Shivdaspur, Varanasi’s red light district, mould and rot were eating away at the very foundations of the structure, but Deeksha and her mother had added a little colour by painting the walls a striking pink. ‘I was told I was going to be sent to Bangladesh, where I would be sold into the sex trade.’ She paused to wipe away the tears welling up in her hazelnut eyes. ‘I thought I would never see my family again. I thought I was going to die.’

I’ve been a frequent visitor to Varanasi for the past 30 years. It’s a city that has cast its spell on me – the colours, the life, the sense that this is where it all began and where it all ends. But here I was face to face with a different Varanasi. This was the holy city tainted.

I was introduced to Deeksha, as well as a number of other young girls with equally terrible stories, by Ajeet Singh, the founder of an organisation called Guria India, whose mission is to stamp out human trafficking and the sexual exploitation of women and children in Varanasi and elsewhere in India.

It might seem strange that in a city as pious as Varanasi people smuggling and forced prostitution exist at all. And while it’s certainly true that it’s not as big a problem as it is in larger Indian cities such as Delhi and Mumbai, it’s still well entrenched in Varanasi. Indeed, prostitution, in some form or another, has a very long tradition in much of India, and at one time, it was considered a highly respectable profession. Known as Nagar Vadhus (‘brides of the city’), the women involved were a cross between courtesans and the geishas of Japan. Always very beautiful, Nagar Vadhus, who were hired as entertainers by the rich and powerful, were trained in the arts and were talented dancers and singers. Although they couldn’t be forced into doing things they didn’t want to, sex was one of the services they might offer. During the Mughal period in northern India (when they were known as tawaif), these women performed mainly for the nobility. Some became rich and powerful in their own right. But, when the British colonists took control of India, they frowned (in public, at least) on such activities, and the tradition quickly died out. The Nagar Vadhus found themselves on the street with little choice but to sell their bodies. Things have changed little since.

Ajeet’s first encounter with Varanasi’s sex workers occurred in the late 1980s, when he attended the wedding of a relation. ‘There was a girl, a sex worker, who was paid to dance. I was shocked by the scene. It’s an old tradition in India, but this was all so sexualised and the men watching were just jeering at her. She was nothing to them.’ At the end of the evening, Ajeet, who was only 17 years old at the time, approached the girl and said he wanted to help her. The dancer, who was in her early 20s, laughed at his suggestion but, true to his word, Ajeet helped to pay for the upbringing of her children.

Inspired to do more to help people like the wedding dancer, Ajeet set about creating Guria India. At first, he simply set up some chairs on the side of the street in the red light district and started giving informal school lessons to children who were otherwise missing out on an education. This quickly got the attention of the neighbourhood’s pimps who, unimpressed by his efforts, did their utmost to disturb the lessons. ‘But, I’m thick-skinned,’ Ajeet explains. ‘And continued until they eventually started to ignore me’. From then on Guria India slowly started to grow in size and ambition and in the years since, Ajeet and his team, which includes his wife and teenage daughter, have changed the lives of thousands of girls caught up in people trafficking and the sex trades.

Due perhaps to its shady and secretive nature, nobody really knows how many sex workers there are in India. Figures range from 800,000 up to ten or even 15 million. Ajeet believes the real figure is at the upper end of these estimates and that at least 1.2 million sex workers are children. He goes on to tell me that while prostitution is legal in India, related activities, such as pimping and brothels, aren’t. This means that sex workers live in a murky grey area open to exploitation by all. He also tells me that the huge majority of sex workers are victims of human trafficking and have then been forced into prostitution. A study by the London School of Economics in the UK in 2020 reported that 95 per cent of trafficked persons in India are forced into prostitution. Perhaps most shocking is the fact that, like Deeksha, most of the victims of trafficking in India have been sold into the sex trade by friends or family members, rather than simply abducted by criminal gangs or pimps.

It’s thought that the industry could be worth up to US$8 billion annually in India alone. And wherever sums of money like this are to be found, corruption is unlikely to be far behind. Sitting in the rather chaotic offices of Guria, where seemingly every flat surface is covered in a storm of piled-up papers tied into bundles with string, Ajeet tells me that because of this corruption, every day is a battle for Guria and the women and girls it represents. It took Ajeet years to gain the trust of the sex workers in Varanasi. ‘They learn quickly to trust nobody,’ he says. ‘They can be killed over just a few rupees, and nobody will care.’

But, it’s not just the women whose lives are in constant danger. Ajeet’s life mission has also taken a hard personal toll on him and his family. ‘There have been 27 serious threats against me, my family and my team,’ he says. ‘We are fighting dangerous people. Not just pimps, brothel owners and smugglers, but also corrupt police, judges and politicians. I have had death threats and mysterious accidents in my car. Some of my legal advisors have been beaten and had bones broken. My daughter doesn’t attend school anymore because of threats she has received on the way to and from school. She has to home-school nowadays. My wife has also been threatened. We have to be careful at all times.’

Once Ajeet and his team have got the women and girls out of immediate danger, they turn their attention to obtaining justice. But for victims of human trafficking and the sex trade this is no easy task. ‘The justice system in India is very slow as well as corrupt,’ says Ajeet. ‘Sometimes it takes so many years for a case to get to court that all the accused have died anyway!’ But even so, the Guria team help the women and girls deal with the nitty-gritty of India’s convoluted legal system. Five years after Deeksha’s ordeal at the hands of her cousin ended, the case is finally about to go to court. A team of lawyers who volunteer with Guria have spent the past few weeks giving Deeksha training sessions on how to deal with the pressures of appearing in court and facing her accused. A few days after I met her at her home, I was invited to sit in on a mock cross-examination.

The three lawyers involved in her training were all smiles when Deeksha and I stepped into the room and Deeksha seemed relaxed in their presence. But, as soon as the lawyers snapped into character, with one playing at being the judge, another the prosecuting lawyer and another the defence lawyer, the smiles vanished and they became brusque, argumentative and hard-nosed. I noticed straight away that Deeksha immediately became more nervous, tying her fingers into knots and trying not to be confused by questions designed to trap her. One of the lawyers, who preferred not to be named, later told me that when it came to India’s legal system, the victims of human trafficking and forced prostitution have the odds stacked against them from the start. ‘It’s hard enough for the women to stand in court and talk about what happened to them, but in the Indian justice system, there is corruption everywhere. Even before cases get to court, the pimps and brothel owners pay off the police and judges.’ Banging his hand down on the desk and sending a sheaf of papers flying onto the floor in the process, he explained that for the accused, there’s a near 90 per cent acquittal rate. ‘Either the victims pull out at the last minute because of intimidation from criminal gangs or the judges and police have been paid off anyway.’

But, despite the obstacles and the violence, Guria has scored some notable successes both in Varanasi and in India as a whole. Over the years, they’ve rescued more than 6,000 victims of human trafficking and forced prostitution. They’ve also set up a witness protection programme and established a support booth for runaway and vulnerable children at Varanasi railway station. They’ve helped bust some major people-smuggling and forced-prostitution gangs, advised many governmental and private organisations, and brought the issue of human trafficking and forced prostitution into the media. And, Ajeet told me with obvious pride: ‘We’ve made Varanasi’s red light district completely free of under-age sex workers. It’s probably one of the only cities in India with no child prostitutes.’

However, just because there are no child prostitutes in Varanasi, that doesn’t mean the children aren’t affected. In the heart of the Shivdaspur red light district is a sky-blue coloured house that acts as a Guria-run nursery school for the younger children of the sex workers and a vocational centre for older children and their mothers. On the surface, in this neighbourhood of despair, the building appeared to be a little sanctuary of smiles where the children play games, get stuck into elaborate art projects, learn computer skills and play music. But, even here, the reality of the environment keeps showing its ugly face

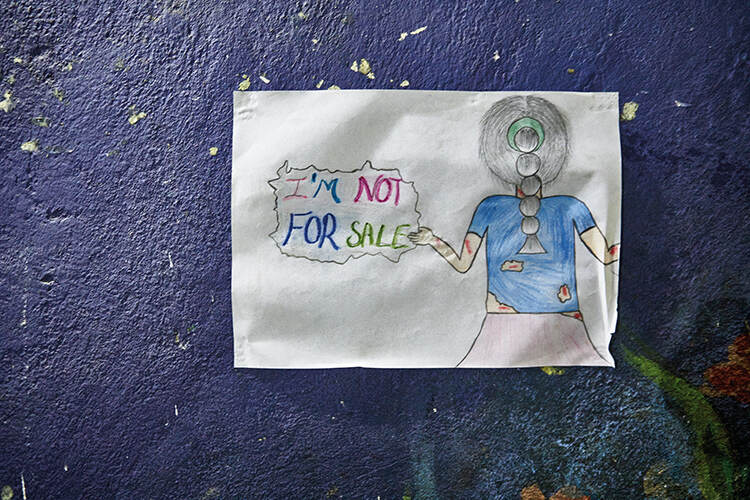

Many of the mothers of these children were trafficked and forced into prostitution, and when I was shown around the centre, I couldn’t help but notice that tacked to the walls were drawings and paintings done by the children in bold primary colours depicting the life they saw on the streets around them. Women in chains, children bound and gagged, pimps with aggressive features and even grey-shaded pencil drawings of their own mothers stripping for clients.

Despite the horror of her story, in the end, Deeksha was, in a sense, one of the luckier ones. Before she could be sent on to the red light districts of Bangladesh – where, like so many before her, she almost certainly would never have been heard from again – she was rescued and returned to her relieved family. And now, under the guidance of Guria and back at school, she is able to start to rebuild her life. ‘My court case is coming up. I’m not scared. I will never let my cousin and auntie get away with what they did to me. I will never let them be acquitted.’

Shortly after I left the City of Light, and just days before her case was due to be heard, the courts postponed Deeksha’s case. Meanwhile, those who drugged her, beat her, raped her and tried to sell her into a life of prostitution remain free to wash away their sins in the Ganges. At the time of her abuse Deeksha was just 11 years old. Where there is light, there is also darkness.