In this rare interview we ran last year, the late Brazilian photographer talks to Graeme Green about his life behind the lens

Sebastião Salgado, the celebrated Brazilian photographer whose profound black-and-white images captured the dignity and hardship of marginalised communities across the globe, has died aged 81. Known for his uncompromising humanism and powerful storytelling, Salgado’s work transcended photojournalism to become visual anthropology. In tribute, we are republishing this rare interview where he reflects on the light, both literal and metaphorical, that shaped his vision.

‘Sometimes I ask myself: “Sebastião, was it really you that went to all these places?”’ the Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado tells me when I raise the sheer scale and spread of his vast body of work. ‘Was it really me that spent years travelling to 130 different countries, who went deep inside the forests, into oil fields and mines? Boy, it really is me who did this. I’m probably one of the photographers who’s created the most work in the history of photography.’

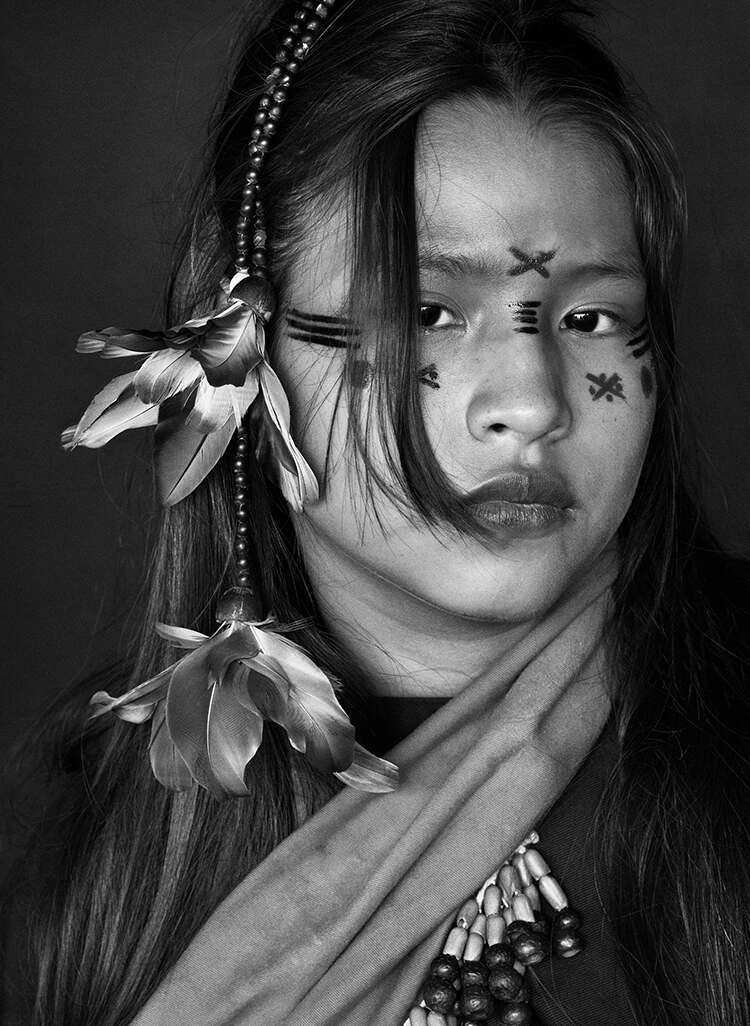

Salgado may have surprised himself, but he has also astonished the world. The body of work he’s produced over the last half-century is remarkable not only for its vast scope, with scenes of beauty and horror – from the Amazon and Antarctica to the Ethiopian famine and the burning oil fields of Kuwait – but also for the consistently masterful quality, one mesmerising, black-and-white masterpiece of light, composition and moment after another. His focus has been humanity, including workers, refugees and Indigenous peoples, and, although he argues that his job as a documentary photographer is only to create ‘a representative cut of a reality’, his work has frequently exposed inequality, hardship and injustice.

‘Photography is a way of life,’ he says. ‘Each photographer works with his own ideology, his history, his heritage. I can’t say my work is because I’m an “activist” or that I want to show the plight of people being exploited. Of course, I’m a guy from the Left – I’m a Leftist. I was working in these places because I am part of a society that needs to see what is happening on our planet.

‘But I grew up in a Third World country,’ he adds. ‘I see the injustice that we have on this planet. I have a big hope that we can have a better way to live, a better situation for the health of our planet, and better social protection for everyone on this planet.’

Salgado is speaking to me via Zoom from his studio in Paris; he divides his time between France and Brazil. In the background is a silvery line of trees, one of his photos of an igapó, a flooded forest, taken in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. I’d expected him to be an austere character; in portraits, he usually appears quite solemn. But he’s often passionate and poetic, his hands moving in a blur as he expresses himself, a musicality to his rising and falling voice.

In April, dozens of his best-known images will be on show at the Sony World Photography Awards 2024 exhibition at Somerset House in London, with Salgado the recipient of the Outstanding Contribution to Photography award, one of many honours in his lifetime. ‘I hope to be alive until then,’ he jokes.

Having just turned 80, he’s keenly aware that he has more years and photographs behind him than ahead. But looking at what he’s achieved, he says, feels surreal. ‘It’s not pride that I feel – it’s a fascination. It’s amazing where I went, how I had the strength and belief in what I was doing. Today, looking back to the beginning, it’s interesting for me to think about all of that.’

EARLY YEARS

Salgado was born in 1944 in Aimorés in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. ‘A very beautiful region of Brazil with high mountains,’ as he describes it. ‘The rainy season’s arrival brought the most beautiful light you can imagine. That light is inside me.’

He studied for a Bachelor of Arts and a Master’s degree in economics in Brazil and a PhD in Paris, then worked for the International Coffee Organisation, occasionally travelling to Africa with the World Bank. Aged 27, he borrowed a camera from his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, who was studying architecture, for a work trip. ‘I can remember even now the smell of this camera: a Pentax Spotmatic II,’ he says, inhaling for effect. ‘When I looked for the first time through the viewfinder, I understood exactly that my life had changed.’

Salgado began his career as a professional photographer in Paris in 1973 and went on to work with photo agencies Sygma, Gamma and Magnum. He captured the attempted assassination of US president Ronald Reagan in 1981. Together with his wife, he later established his own agency, Amazonas Images. Over the past 50 years, he has worked on a series of long-term projects, including the recently reissued Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age, a monumental book, first published in 1993, in which Salgado documented manual labourers around the world at a moment in history when he saw machines and automation starting to replace people. Workers contains some of Salgado’s most famous pictures, including thousands of men trying to get rich in the infernal Serra Pelada gold mine in northern Brazil and oil workers fighting to contain burning wells in Kuwait in the aftermath of the first Gulf War, as well as textile workers, cocoa, tobacco and tea farmers, car manufacturers and producers of lead, steel, iron and coal, from Cuba to Kazakhstan.

‘I decided to take a lot of pictures to show the end of an era,’ Salgado explains. ‘I wanted to photograph these things before they were gone.’

The introduction to Workers includes the line: ‘So the planet remains divided, the First World in a crisis of excess, the Third World in a crisis of need.’ Economics has long been a lens through which Salgado looked at the world, his book illuminating the disparity between rich and poor, between owners and workers, and between consumers and producers. ‘When you see England, the big squares and beautiful buildings in London… This is not the product of the British workers,’ Salgado argues. ‘This is the product of the work of all the guys around the planet, which the financial system transfers to England. In the mines in Brazil, we gave the rest of the planet all our iron ore: France, England, the United States…

‘When you see guys working in an office in England, they have a salary, enough money to buy a house, a car, holidays and maybe to save a little. Their work is easy and clean,’ he continues. ‘The majority of people on the planet don’t work like this. In Rwanda, the guy producing tea goes to work at six in the morning, when the sun rises, and works for 12 hours. He goes back home when the sun sets. He has no car, no house, no shoes. His kids don’t go to school. The price for what he produces is fixed in the stock markets of London or Chicago or Paris. We underpay for the product he works on, and everything’s transferred to us.’

The photographic stories in Workers often show people labouring in dirty, hot, dangerous conditions. ‘The work is about movement – all day long the same movement. At the end of the day, the worker is tired of doing the same movement. He goes home, but tomorrow morning he must start again with the same movement, and after one month or ten years, he’s doing the same thing. Many people do not know how hard it is to really work in a mine or a factory. We have hidden that.’

A TURNING POINT

Over the years, Salgado has spent weeks or months working in challenging situations, bearing witness to suffering and the worst sides of humanity. His experiences in 1994 during the Rwandan genocide nearly made him leave photography behind, but instead led him in a new direction. ‘I came out of the Rwanda genocide sick,’ he says. ‘I was sick from what I saw there. My parents were getting old and they made the decision to give their farm to me and my wife. We saw so much environmental destruction there. We were not environmentalists, but we started to replant the rainforest.’

In 1998, Salgado and his wife established Instituto Terra in Aimorés, a large-scale project to restore the Atlantic Forest. ‘It was amazing,’ he says. ‘We had a land completely devastated, eroded, and in a few years of planting trees, we had all the life coming back – not just the vegetation, but insects, birds, mammals, predators… I was about done with photography after Rwanda, but now I had a huge wish to photograph again. It’s then that I conceived a project to see the whole planet, to see what was pristine and hadn’t been destroyed.’

The resulting book, Genesis, took eight years, with adventures to more than 30 different locations, Salgado photographing not only people but, for the first time, concentrating on natural landscapes and wildlife, from marine iguanas in the Galápagos to penguins on massive icebergs in Antarctica. ‘The big trip was inside myself, to discover that I, also, am biodiversity,’ he tells me. ‘I am just one animal. It was one of the hugest discoveries of my life.’

He notices a portrait of a silverback gorilla on the wall behind me and goes on to describe a memorable encounter. ‘In Rwanda, I had a young gorilla sit right in front of me. It’s forbidden for us to be too close, but sometimes they come close to you. I started to photograph. He put his thumb in his mouth,’ Salgado says, reproducing the gorilla’s gestures. ‘Then he took it out. I realised he was looking at himself in the mirror of the big lens of my camera. He was seeing himself. Oh my God, just as humans have done, this gorilla was discovering himself, who he is. I was right in front of him as he made this jump of evolution. I was so moved that I cried.’

Salgado’s concerns about the state of the natural world also inspired his recent Amazônia project. ‘When I went for the first time to the Amazon about 40 years ago, 100 per cent of the Amazon was there,’ he recalls. ‘Now, we have about 80 per cent left. I’ve been completely shocked. It was necessary for me as a documentary photographer, as a Brazilian, to show what was going on. I took a decision to show only the pristine Amazon, not the destroyed Amazon, so people would have an idea of what we are about to lose. We are about to lose paradise.’

Salgado made 48 trips to the Amazon over six years, living with and documenting the lives of Indigenous communities, including the Yanomami, Asháninka, Awá and Macuxi. ‘They’re the predecessors of humanity,’ he says. ‘But when you meet them, they’re exactly like you and me. They are us. What is essential for you in England or for me in France is essential for them, too. But with the difference that they live in total communion with nature. When an Indian baby rolls on the ground or a child jumps into the river, the mother doesn’t say anything – he’s inside his element. You and I are no longer with our planet. We have become aliens on our planet.’

FUTURE FEARS

Salgado’s lifetime of experiences, from conflict to environmental destruction, hasn’t left him optimistic about humanity. ‘I’m very concerned for the future,’ he says. ‘We are heating the planet very fast. We are destroying forests, destroying the environment, destroying wildlife. We are killing the planet. I have a hope that if we can start the rehabilitation of the planet, we can survive, but it will be very difficult. We have started to experience hard times, and the future will be very hard for the people in the world who are most poor.’

Instituto Terra continues to be Salgado’s beacon of light. In the 25 years since it began, they’ve planted more than 1.1 million trees and rehabilitated around 2,000 water sources. The project employs more than 100 people. So far, it has cost around £22 million.

‘We’re fighting hard. I sold a lot of pictures to collectors for this,’ he says. ‘I don’t need money. I have an apartment, a car, a way of life… All the money goes to planting trees, which means I have hope for the future. We just bought new land there. We’re growing the size of the project. I’m excited about what’s happening in the next year. We’re creating a huge forest.’

The institute and restoring the forest were Salgado’s wife’s ideas. Lélia has been a major part of Salgado’s professional life. She’s the director of Amazonas Images and helps write and design his books and exhibitions. The couple got together in 1964 and married in 1967. ‘I’ve lived with my wife for 60 years – I was 19 when I started with her and she was 16,’ he says. ‘It was the most important event in my life. My wife encouraged me to go and do this work. She had huge optimism when I decided to leave economics. At that time, I worked in London and made a huge amount of money. We had a TR6 Triumph, the most beautiful sports car, and an amazing life, and we gave up everything to start from ground zero. We built our lives together. I don’t know where my life finishes and my wife’s life starts. My wife is 77 years old and I love her the same way as when we met 60 years ago.’

The couple has two sons. ‘We have a Down syndrome kid, who has transformed our lives,’ Salgado tells me. ‘We never put him in an institution. He goes in the morning and comes back in the afternoon, but he lives his whole life with us.’

At 80 years old, Salgado seems animated and energetic. ‘I feel well,’ he says. ‘There are things I can’t do any more. With my age, all your cells start to die. I have a blood problem that made me a little bit less strong, but the doctors believe I can live for many years.’

He continues to travel and take pictures, recently working with a drone for the first time (‘What a discovery. I did incredible things.’). But he’s more occupied with editing past collections and attending to his substantial archives. There will be no more ambitious, multi-year projects. ‘I have no more strength to do that,’ he says. ‘I have no more age to go – 80 years is a lot of years.’

He becomes visibly moved as he looks back. ‘The best moments in my life were the moments I was going into new worlds, going to meet people, going to discover, going to see things I’d never seen before. That was, for me, the big, big pleasure. And the second big pleasure was always the last day, when I got the last cab to go to the last airport to come back to my family, to my wife and my kids. That was always such a huge pleasure, too.’ He pauses to wipe his reddened eyes. ‘That was my life.’