Africa now has a solid middle class, coinciding with more aid for development and an end of wars that had dogged the continent in the 1990s

By Richard Dowden

opinion

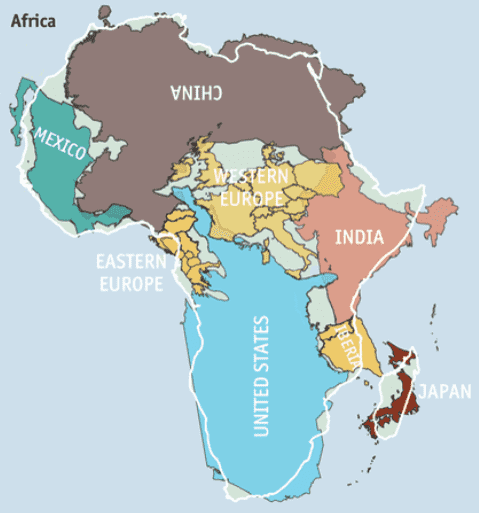

Africa. Only one other continent in the world – Australia – has similarly defined boundaries. Where does Europe begin and end? What does America mean? The United States? And Canada? What about South America and the Caribbean? Where does Asia start and end? Africa is a clearly defined shape surrounded by water – and is vast. You can fit the USA and China in and still have room to spare. The distance between London and Moscow is the distance between the mouth of the Congo River and its eastern border with Sudan.

Because it is clearly defined, Africa is an easy target for generalisations. Many outsiders are happy to dismiss the continent with a selection of single words: backward, poor, corrupt, hopeless. Its labels include ‘the Dark Continent’ or ‘the Hopeless Continent’. Book titles also often portray violent dramatic images – What if Africa refuses to develop? False start in Africa, Africa in Crisis, Aid on the Edge of Chaos, Africa Betrayed, Black Man’s Burden, Criminalisation of the State in Africa, Wars, Guns and Votes, The Politics of Suffering and Smiling, The Looting Machine. More recently there have been different dreams – ‘Africa Rising’, ‘Emerging Africa’, ‘African Renaissance’.

Above all, these adjectives are reductive, one-dimensional. They are based on a single view based on one or two countries. No one would describe Asia, America or Europe in such simplistic ways.

The top and the bottom of Africa’s pyramid of wealth are easy to define. At the very top are the multi-millionaire – often billionaire – super-rich. These are mainly presidents, ministers and their cronies who control the corruption cartels. Much of that wealth is siphoned out of their countries in collaboration with non-African partners and banked in Europe, the Middle East or Asia. Continent-wide, these super-rich probably number a couple of thousand. They have palaces in Africa and palatial homes in Paris, London or other capitals. Robert Mugabe had palaces in Hong Kong and Kuala Lumpur.

At the bottom of the pile are the rural and urban poor – about 400 million of them – who live on less than two dollars a day and work long hours to stay alive. They will own a pair of repeatedly-repaired shoes, a pair of trousers – or a skirt – and a shirt that hangs on a nail with possibly a second one for Sundays. Their home will be made of sticks and mud with flattened tins for a door. Richer ones will have a wooden bench bed. The rest will sleep on a grass mat on the floor. Thanks to cheap Chinese goods, this class is better off than it was 20 years ago, but the gap between rich and poor is still vast, and without education their chances of life getting better are slim.

So who is in the middle? What do they do? The economic definition of middle class in Africa is so vague that it is almost meaningless. Outsiders’ definitions by income do not help. These are some estimates:

- Standard Bank, 2014: 7.6 million earning between $23 and $115 a day.

- McKinseys, 2008: 15.7 million earning more than $55 a day.

- The OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development), 2014: 32 million earning between $10 and $100 a day

- ADB (African Development Bank), 2010: 327 million earning more than $2.2 a day.

Then there is Vijay Mahajan’s fantasy picture in his 2007 Africa Rising book proclaiming that Africa has 900 million consumers. I suppose if you count everyone who is lucky enough to eat every day as a consumer, and then describe them all as a consuming middle class, then almost everyone can be counted.

The middle-class occupations will be the civil service, business, entrepreneurs or employees of large local or international companies. They will own a house and a car and will send their children to private schools. If they have enough money, these schools will be in Europe and America but, increasingly, middle-class Africans send their children to India or other Asian countries. And in recent years there has been a rapid increase in good fee-paying schools in Africa itself. The thirst for education is immense.

But the middle classes are undergoing a profound change in almost all African societies. The nuclear family is goring at the expense of the extended family. The first post-independence generation of African professionals found they had to share their incomes not just with their immediate family, but with their extended families as well, who trace their families back several generations and stay in touch with cousins several times removed. Today, the middle classes are gradually dropping these extended family obligations. Modern urban life means you look after your own children – two or three only – and you may pay for the funeral of a respected uncle or aunt. But you no longer pay school fees for children of distant cousins you barely know.

Few of Africa’s middle classes rely simply on their salary as they would in Europe and America. In addition to the day job, many will inherit land which will produce both food for the family and another source of income. Secondly, they are well placed to buy land around the burgeoning towns and build on it. Many will exploit the dying family structure by employing poor members of the extended family as domestic servants or workers on the family estate. Thirdly, they will have their private businesses, for example owning two or three cars and hiring drivers to use as taxis. None of this will be declared to the taxman. Nor will it appear in any World Bank of IMF figures. Whatever the surveys say, the African middle class is much bigger and richer than anyone thinks – as indeed is the economy of the whole continent.

In the 1970s, African economies grew at 4.2 per cent, in the 1980s at 1.8 per cent and in the 1990s at 2.6 per cent. High commodity prices – especially oil – gave countries like Angola, Equatorial Guinea and Libya growth rates in double figures between 2000 and 2010. But other non-oil countries were doing better too, thanks largely to higher commodity prices and the end of the catastrophic wars of the 1990s.

‘Africa Rising’ they called it. Some saw it as the new Asia, a soaring economic miracle that would transform the entire continent. The combination of minerals, agriculture and a new middle class drew investment from Europe, Asia, and even from North America. Mobile phones meant that Africa could talk to the rest of the world.

Africa could have risen after 2000. The rise in its commodity prices, global connectivity and better economic governance could have allowed African government to make bold investments in energy and infrastructure. They could have followed Southeast Asia and invested in adding value to Africa’s resources.

Why didn’t every African government try to research gaps in the global market, invest in infrastructure, and give tax breaks to entrepreneurs who would turn Africa into the workshop of the world? Instead, they relied on raw commodities for wealth. With the world in recession, that window is closing fast. China is pulling back from Africa, and African economies will be back at four to five per cent growth. Deduct 2.6 per cent for the increase in population, and that means Africa has less than two per cent real growth. The gap between most African countries and the rest of the world will grow wider.

Africa’s population will double by 2050. I sense that the next generation in Africa will be less tolerant of their ageing rulers and there will be more and more young people getting increasingly frustrated. They will be desperate for jobs but will not have enjoyed the global standard of education.

Having missed this generation’s opportunity to turn African cities into the workshops of the world, the immediate task is to go for agriculture so that Africa can feed itself and perhaps process and export food. African governments must invest in rural areas and develop agricultural policies and make faster, cheaper services and mobile phone access available.

But while predicting an explosion of youthful energy or frustration, I am aware of Africa’s other great talent: patience. It is not an idle, resigned patience but an ability to wait and watch until everyone is ready. Africa’s way feels somehow connected to a patience and wisdom that we have lost in our time-pressed world. Maybe that patience is Africa’s gift to the world.

Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society