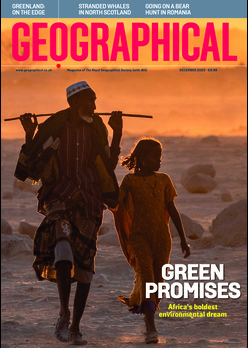

The release of the latest IPCC report suggests it’s ‘now or never’ if we want to tackle climate change

By

The new report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the third in a three-part assessment of the scientific knowledge of climate change, its causes, potential impacts and the response options. Each report is authored by a ‘working group’ of hundreds of climate scientists from countries around the world and comprises thousands of research studies. The latest, titled Mitigation of climate change, presents the current efforts being taken to tackle global warming, and what is needed to keep it well below 2°C.

What are the main conclusions of the IPCC report?

Despite the global nature of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, average annual greenhouse gas emissions between 2010 and 2019 were higher than at any other time in human history. The rate of growth has slowed, but not enough. Evidence from the report suggests that another decade of similar emissions would use up our remaining carbon budget for limiting global warming to the critical 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

‘Immediate and deep emissions reductions’ are required across all sectors for this goal to remain within reach. Greenhouse gases must peak before 2025 at the latest, reaching a 43 per cent reduction by 2030 and net-zero by the early 50s. Even then, we’re likely to overshoot, but may be able to reign temperatures back in to below a 1.5 degree increase by the end of the century.

The current climate pledges are nowhere near sufficient. On this, the report is clear. That said, it states that options exist in all sections to at least halve emissions by 2030.

What are the main obstacles?

The largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions are the energy supply sector and industry, which accounted for 34 per cent and 24 per cent of all global emissions in 2019. Achieving net zero in the energy sector will be ‘challenging’, but possible, requiring a revolution in the way we produce power and energy. Industrial emissions are the fastest growing of any sector, driven by extraction and production of basic materials, and decarbonisation of the production of steel, concrete and cement will be slow.

In all scenarios, fossil-fuel use will need to be greatly reduced, with the complete phase-out of coal by 2050. However, this is hampered by plans for new coal-fired power plants which the report says must be cancelled, alongside the decommissioning of existing plants. Russia’s war, and a race to solve Europe’s energy crisis that might lead to the reactivation of old coal plants, could throw a further spanner in the works.

Will we need to change our lifestyles?

In a word, yes. Everything from our diets to buildings, transport and our demand for products and services will have to change. The report suggests a strategy that follows an ‘avoid-shift-improve’ framework, such as avoiding long haul flights, shifting to a plant-based diet and improving existing infrastructure to make it greener and more energy-efficient.

Food accounts for 28 per cent of the average household’s carbon footprint, having a greater impact even than energy use, and has the best potential for reduced emissions. Land transport has the second-biggest potential. In 2019, 70 per cent of direct transport emissions came from road vehicles, and the number of passenger cars in use has grown by 45 per cent globally in the last decade. City dwellers in developed countries produce nearly seven times the share of emissions of someone in the lowest emitting region. The richest ten per cent of people on the planet are responsible for between 34 to 45 per cent of all global emissions

Priyadarshi Shukla, IPCC Working Group III Co-Chair, says that with the right policies and infrastructure, lifestyle changes ‘can result in a 40 to 70 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050,’ all the while improving our overall well-being.

What about carbon sinks and carbon capture?

Agriculture, forestry and other land use accounts for roughly 13 to 21 per cent of all human-caused emissions. In addition to carbon dioxide, it’s also driving the rise of the other most damaging greenhouse gases, methane (from manure and belching cows) and nitrous oxide (from fertilisers). Land-use change, especially deforestation for agriculture, is a key culprit, resulting in the loss of tropical and mangrove forests which are critical for carbon storage and biodiversity.

Despite this, our combined natural and managed terrestrial ecosystems continue to be a carbon sink, absorbing around one third of man-made carbon dioxide emissions. Gains have also been made in temperate and boreal forest restoration. The protection and restoration of more forests, as well as peatlands, coastal wetlands and grasslands, must be a priority, although tree planting alone won’t cancel out continued emissions.

The report also assesses carbon capture technologies and geoengineering: large-scale interventions such as spraying aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect the energy of the sun. Both, it concludes, have limited potential, particularly in the short term due to current levels of development.

What is the cost of climate change mitigation?

‘The global economic benefit of limiting warming to 2°C is reported to exceed the cost of mitigation in most of the assessed literature.’ Simply put, the costs, which will still be significant, will be outweighed by avoiding those of the catastrophic impacts higher temperatures will have on society.

Limiting global warming will require investment in new technologies, and investment will need to increase sixfold to make the changes needed. The financial burden must fall largely on richer countries if we are to achieve a successful, global low-carbon transition. But money will be saved by making buildings, transport and industry more efficient, and the costs of solar, wind and batteries have decreased by 85 per cent since 2010.

How will tackling climate change impact development?

The report rejects the idea that less developed nations need fossil fuels to tackle social problems, stating with high confidence that ‘eradicating extreme poverty, energy poverty and providing decent living standards… can be achieved without significant global emissions growth’.

Poorer nations are on the front line of climate change. Accelerated and equitable climate action will be ‘critical to sustainable development’, lessening food insecurity and benefiting human health by improving air quality and potentially resulting in 150 million fewer deaths between now and 2100. ‘We are at a crossroads,’ said IPCC Chair Hoesung Lee. ‘We have the tools and know-how required to limit warming. The decisions we make now can secure a liveable future.’