Seagrass boasts a range of climate-change-fighting qualities, but must be conserved to be utilised in the future

by Victoria Heath

While it may look inconspicuous, seagrass is a hardy, powerful tool in the fight against climate change.

The world’s only flowering plant that can live in seawater, seagrass exists in more than 159 countries across six continents. One of Earth’s most widespread coastal habitats, some seagrass meadows are so large that they can be seen from space.

What is seagrass and why is it important?

Large clusters of seagrass are known as seagrass meadows, often coined as ‘blue forests’ for capturing carbon up to 35 times faster than tropical rainforests. Drawing carbon dioxide from the water from photosynthesis, seagrass then traps the gas within mud.

Despite only covering 0.1 per cent of the ocean floor, seagrass accounts for between 10-18 per cent of the total ocean carbon storage. It also possesses a remarkable ability to remove pollutants from water.

Seagrass meadows also support a wide range of important fish species: 10,000m2 of seagrass can support 80,000 fish and more than one million invertebrates.

The scarcity of seagrass

Globally, it is estimated that an area of seagrass equivalent to two football pitches is lost every hour due to pollution, coastal development and anchor damage. In the UK alone, up to 9 per cent of seagrass has been lost in the last century.

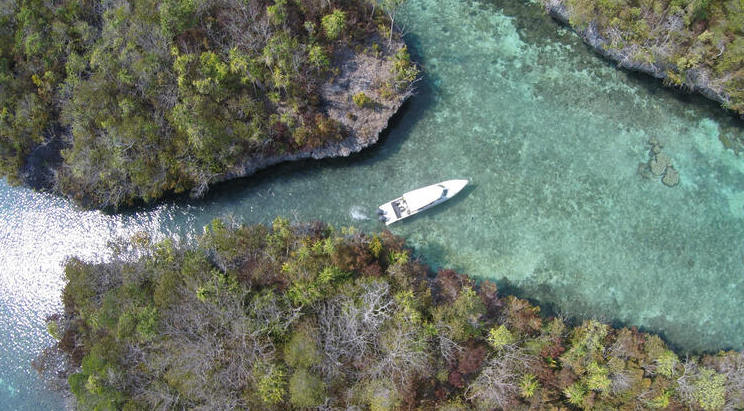

The damage which just one yacht’s anchor causes to seagrass in a single day would take almost 1,000 years to restore. And according to a study in 2019, Europe lost one-third of its seagrass between the 1860s and 2016.

While the answer to seagrass damage may simply seem to grow more, a recent study conducted by the University of Florida found that seagrass meadows have extremely deep roots, and are able to live in the same area for hundreds and possibly thousands of years.

‘If that’s the case, there’s something priceless about the location, not just about the seagrass itself,’ said Michal Kowalewski, Thompson Chair of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History and the principal investigator of the study.

‘If we are unable to prevent seagrass loss in a particular area, we may not be able to make up for that loss by trying to establish a new meadow elsewhere,’ added Kowalewski. ‘This realisation only heightens the need for immediate action aimed at improving water quality in estuaries and coastal waters around the state.

Unfortunately, the long life of seagrass meadows means that they grow slowly, meaning they cannot grow at a rate which outpaces the damage caused by climate change and human activity.

Seagrass has also been damaged by microplastic use. Recent research has shown that microplastics have been found inside seagrass, the lowest level within the ocean’s herbivore food chain. This can be harmful to those who eat it, from vegetarian parrotfish to humans – whose seafood consumption has doubled within the past 50 years.

How do we protect and conserve seagrass?

There are a range of projects being undertaken across the UK to help increase seagrass numbers.

In March 2022, Natural England announced that a new milestone had been reached in the £2.5 million Life Recreation ReMEDIES partnership. Around 70,000 seed bags across an area of 3.5 hectares of seabed had been planted.

The project also includes other methods to tackle seagrass damage, including surveying and mapping seagrass beds to inform recreational marine users and introducing voluntary No-Anchor Zones and Advanced Mooring Systems, created to interact less with the seabed.

In May 2022, the UN also announced March 1st as World Seagrass Day in order to promote the importance of countries taking action in protecting and conserving seagrass. By protecting seagrass meadows, the UN says that countries can achieve several economic, societal and nutritional objectives, aligning with national, regional or global policies.

These include targets set under the Paris Agreement, targets and indicators which are associated with the UN’s ten Sustainable Development Goals and commitments to be made under the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

‘There is clearly a great missed opportunity here, and the potential for more countries to include seagrass as part of their box of tools for mitigating and adapting to climate change,’ says Gabriel Grimsditch, UNEP marine ecosystems expert.

Despite the promise that seagrass can hold in combating climate change, factors such as project size can affect the success of its ability. Evidence suggests that the smaller a project is, the more likely it is to be damaged.

‘Humans do not yet have long-term experience of planting at sea, in contrast with our many centuries of experience on land. Wherever possible, it’s better to conserve what we already have,’ Grimsditch adds.

Looking to the future

A consortium, which includes WWF, Project Seagrass and Swansea University, has planted over 750,000 seagrass seeds in Dale Bay, Pembrokeshire in the biggest seagrass restoration project undertaken in the UK.

Restoring the seagrass is a labour-intensive process, involving a complex process of filtering hundreds of thousands of seeds via pumps into hessian bags which are then planted into loch beds. The survival rate of seagrass is just 10 per cent, meaning that the new seagrass could take anywhere between five and seven years to grow and connect with other older seagrass to form a meadow.

The consortium aims to restore 3,000 hectares of seagrass meadows in the UK by 2030. An area of seagrass that large could capture the emissions of 3,000 small cars, support 4,700 more fish than bare sediment alone and create a habitat for billions of small animals.