There is a rising awareness of the damage war inflicts on the environment. The Ukrainian government are pushing to get the issue on the agenda in a bid to secure reparations

Report by Catherine Early

Prominent at both the COP15 biodiversity talks in Montreal in December and the COP27 climate meeting the month before in Sharm El Sheikh were Ukraine’s efforts to highlight the environmental damage that the Russian invasion is doing to the country.

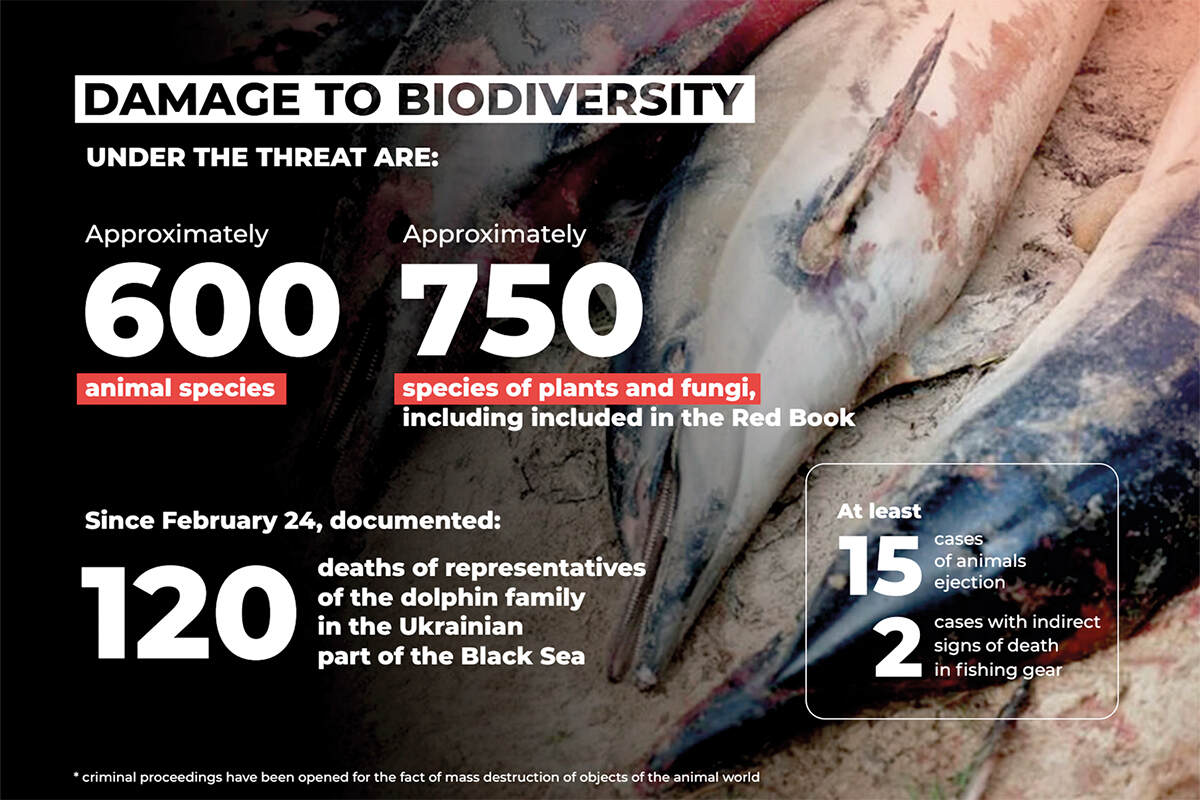

The government of Ukraine is keen to get the issue on the agenda. In a Montreal speech, the country’s environment minister, Ruslan Strilets, started by saying: ‘Ukraine defends not only its people but also humanity. Our state is a habitat of about 74,000 species of flora and fauna. By destroying our home, Russia is also destroying their home. Russian occupiers are trying to destroy all of Ukraine, thus endangering more than a third of Europe’s biodiversity.’

Amid the human carnage – at least 6,884 civilians killed, 10,000 injured, possibly more than 200,000 troops on both sides killed – the Ukrainians are determined to ensure that Russia is also held to account for the awful impact the war is having on the region’s natural environment. It has logged more than 2,000 cases of severe environmental damage and publishes regular updates and details of air pollution incidents and contamination of ground and surface water. The damage is being recorded with the help of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

‘Calculating the damages is a way of getting reparations from Russia in the future,’ Strilets said, citing the case of Kuwait, which was awarded US$52.4 billion in compensation from Iraq following its invasion and occupation of the country in 1990–91. A compensation commission created by the UN to deal with Kuwaiti claims arising from Iraq’s invasion found that the aggressor was liable under international law for the damage it caused, including the depletion of natural resources.

‘We have much bigger and richer biodiversity, so we understand the damage could be much higher than the damage in Kuwait,’ Strilets told me. His ministry estimates the environmental cost of the war so far at €37.8 billion, including €11.9 billion damage to soil and €25.5 billion damage from air pollution.

At the COP27 climate talks, Ukraine hosted a pavilion where it held discussions and showed documentaries about the environmental damage from the war. Many senior politicians, including the US special envoy for climate John Kerry and European Commissioner for climate Frans Timmermans, visited the pavilion.

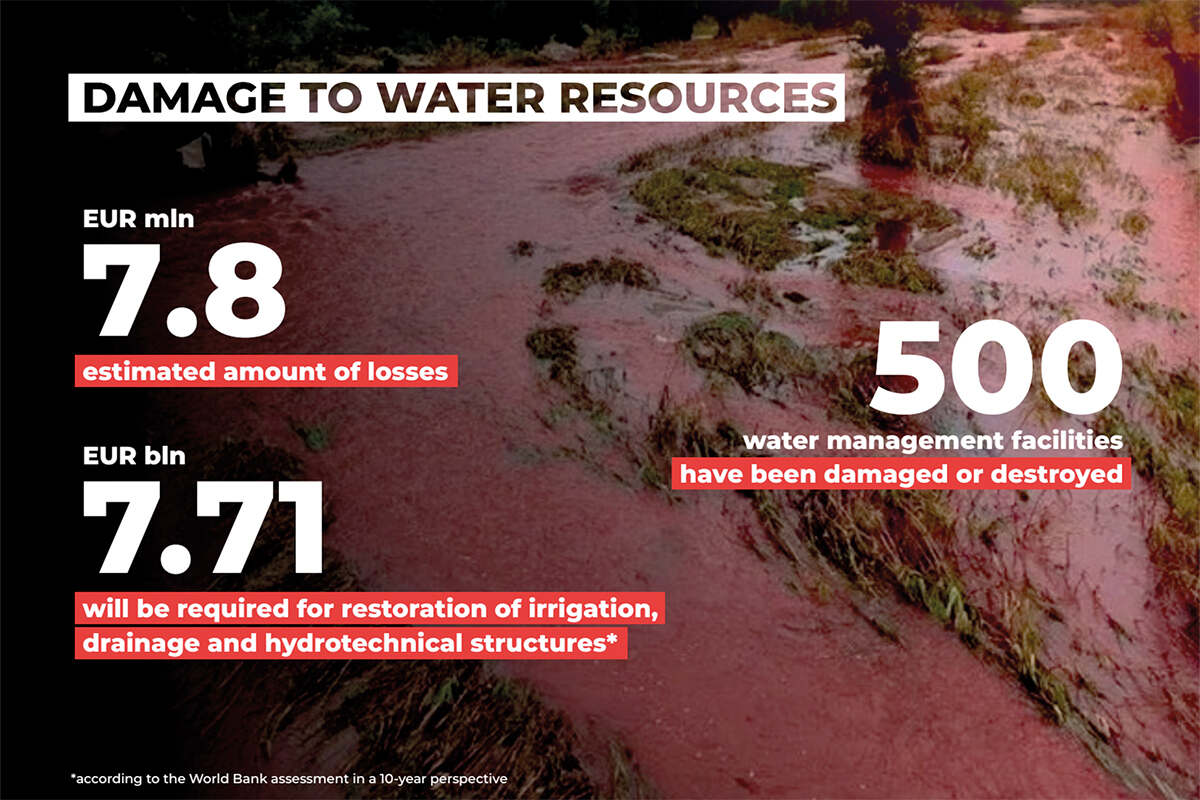

‘I felt and saw that they support Ukraine. It’s very important to increase the temperature of the information stream,’ Strilets said in our interview in Montreal. He added that pollution caused by the war poses a real threat to people, both as they try to survive the conflict and when they return to their former lives once it’s over. Basic infrastructure needed for daily life, including water pumping stations, purification plants and sewage facilities, has suffered significant damage. Multiple industrial facilities, warehouses and factories, some storing hazardous substances ranging from solvents to ammonia and plastics, have been damaged.

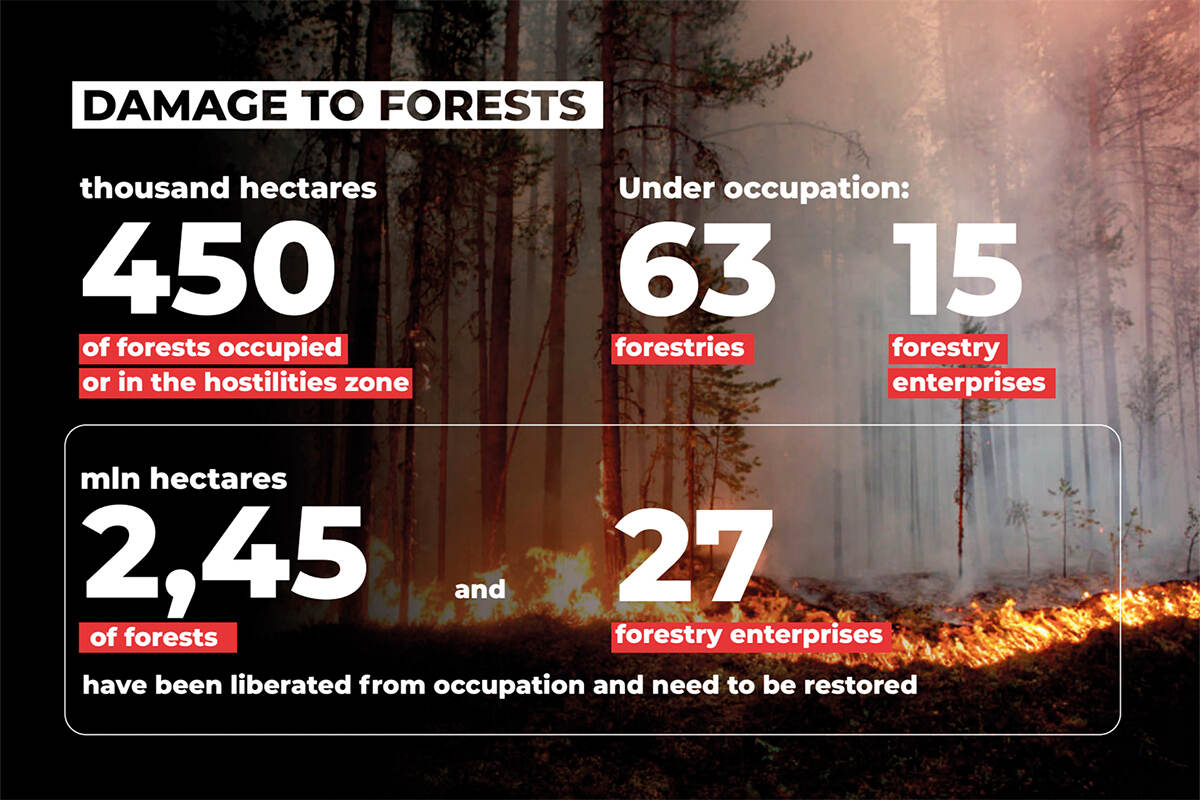

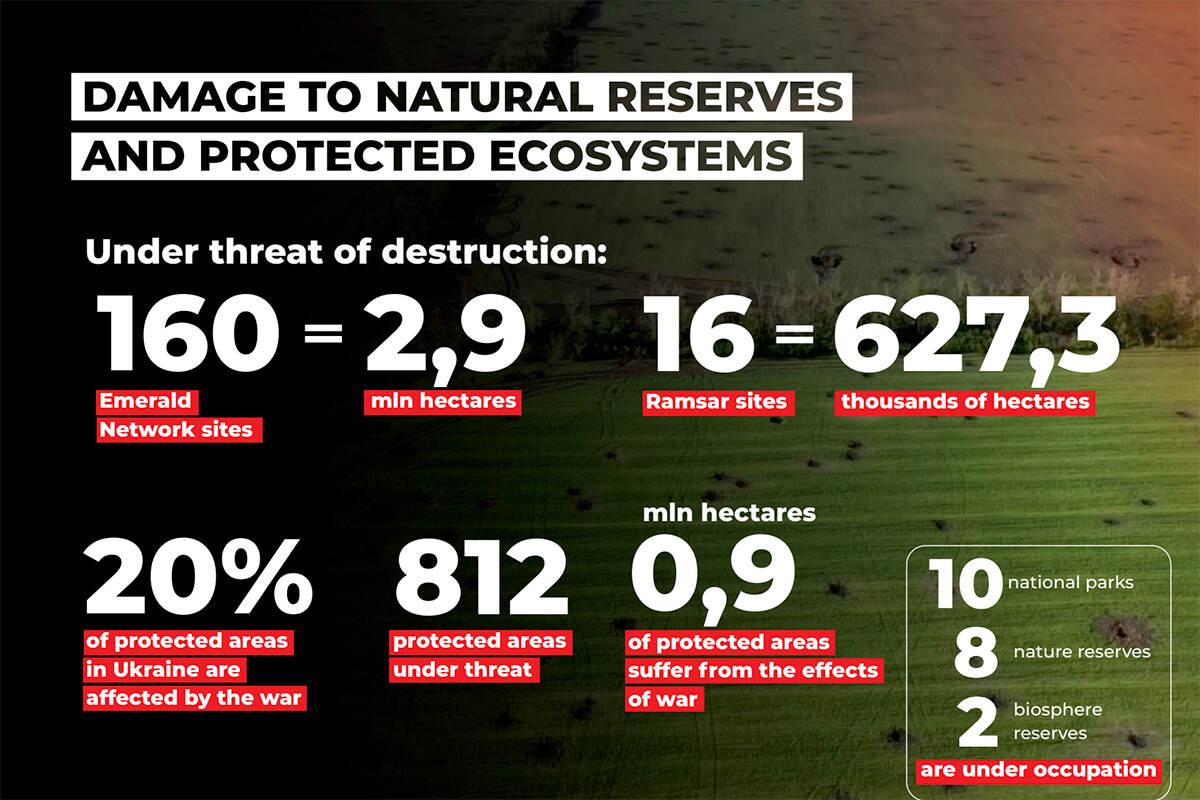

In addition, there has been significant damage to conservation areas – the Ukrainian government estimates that 20 per cent of protected areas are at risk, including 16 Ramsar wetland sites and ten national parks. One-third of the country’s forests have been damaged and are now peppered with landmines.

‘Most of the fighting takes place in the forest – almost 450,000 hectares of forest are occupied or are in the war zone,’ Strilets said. ‘The Russians have turned our natural resources into military bases. Nature is priceless, but we have monitored environmental damage on a scale never seen before.’

In the longer term, Ukraine will need a significant clean-up of air, soil and water to enable those who’ve fled to return. Explosions in agro-industrial storage facilities, including fertiliser and nitric acid plants, have released hazardous substances. Large volumes of military waste, including destroyed military vehicles, are also causing pollution, while debris from damaged buildings contains asbestos. Eastern Ukraine, in particular, will suffer long-lasting effects where the closure of coal mines has meant that groundwater is no longer pumped out, leading to flooding, contamination of water sources and methane leaks.

‘The impact will last decades and will have long-term and reverberating effects on livelihoods as well as health,’ said Doug Weir, research and policy director of the Conflict and Environment Observatory Unit, which monitors and campaigns about the environmental impacts of war.

Examples of long-term environmental impacts caused by war can be seen in other countries. In Afghanistan, decades of conflict have led to extensive deforestation, which has left communities far more exposed to the impacts of climate change than would otherwise have been the case, according to Weir.

Another example is in northeastern France, where public entry to, and agricultural use of, about 100 square kilometres of former farmland remains prohibited by law due to contamination from the battlefields of the two world wars.

‘In addition to the need to protect the environment in and of itself, protection of the environment is a humanitarian imperative because humans are utterly dependent on healthy water, air and soil,’ said Weir.

Public awareness

According to Weir, the war in Ukraine has significantly raised the profile of the environmental impact of war, partly due to the use of modern technologies to monitor it.

These include identifying incidents from social media posts and verifying them using satellite imagery far more quickly than in the past, when the UNEP would have to wait until the conflict was over before it could take samples from hazardous sites and produce a report. ‘All of a sudden, we can start reporting on environmental issues in almost real-time, and that’s had a huge impact in terms of visibility,’ Weir said.

Even so, there’s little public awareness about the potential harm to health from pollution in Ukraine, according to Yevheniia Zasiadko from the Ukrainian environmental campaign group EcoAction.

‘Ukraine’s economy is very traditional – a lot of people grow food on their land because it is cheaper and more natural. The economic crisis could mean that people try to come back to the same land, but the east and south of the country have had heavy attacks, so people would be poisoned,’ she said. But, she acknowledged, ‘it’s hard to communicate about pollution because the focus is on other things at the moment’.

Strilets was also sensitive to the fact that people are naturally focusing on the immediate human consequences of the war. However, he pointed out that a government-developed app showing maps of air pollution hotspots and information about radiation has been used by 100,000 people. In return, the public has reported more than 2,000 incidents of pollution to the government via the app.

Legal advances

Ukraine’s hopes for reparations are undoubtedly ambitious, given the limited precedent for this type of claim. According to the University of Essex’s Professor Karen Hulme, who specialises in the legal protection of the environment during armed conflict, Kuwait’s success in gaining compensation was specific to the geopolitics at the time.

‘It was an era when the Soviet Union was willing to work with the West,’ she said. ‘The UN Security Council [of which Russia is a permanent member] agreed on a resolution that held Iraq to account for the damage from its invasion of Kuwait, even what was caused by the UK and US allies. You’re not going to get that now.’

However, recent international developments may aid Ukraine’s cause. In December, the UN General Assembly adopted what campaigners have hailed as the most significant advance in the legal framework to prevent and remedy environmental damage from war since the 1970s. The Protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts (PERAC) principles vary from non-binding guidance to binding international law. Although the principles weren’t enshrined in a treaty due to pushback from individual states, and their usefulness will depend heavily on implementation, the global adoption is a significant step forward, campaigners believe. Under existing rules of international humanitarian law, the environment only enjoyed some protection during conflicts and under occupation, and primarily in international armed conflicts. The new principles specifically address many different types of environmental harm and apply before, during and after armed conflicts. They are applicable to both conflicts between states and civil wars.

They are the result of more than a decade’s work by the UN’s International Law Commission in consultation with governments, human rights experts and environmental campaigners. ‘The principles represent a solid body of research, which a court could find very persuasive,’ Hulme said.

PERAC doesn’t change the threshold above which environmental damages become a crime, Hulme explained. ‘This has been set unrealistically high and has never been tested in the law,’ she said. ‘However, PERAC does stipulate that states should make full reparation for damage caused by intentionally wrongful acts and that this can include the costs of damage to the environment in and of itself, rather than just that used by humans, such as farmland.’

According to Weir, Russia resisted any changes to the legal framework during the development of the PERAC principles. ‘This gives an indication of the extent to which they’ll prioritise it – there’ll always be actors like that who refuse to be constrained by the norms of international law. But there will be some who are.

‘The principles assume a normative baseline of conduct, something that we can point out to states as the minimum they should be doing and develop that further,’ he explained.

Competing priorities

Ukraine’s case was also boosted by a UN resolution passed in September that recognised the need for a reparation mechanism due to Russia’s invasion and suggested the establishment of an international register of damage. Although the resolution doesn’t force Russia to do anything, it still represents a moral victory for Ukraine, Hulme said.

Theoretically, states could create their own mechanisms by which to force Russia to pay reparations, such as the use of the frozen assets of oligarchs, Hulme added. However, in her opinion, that would be unlikely in reality as it would open up a Pandora’s box for any state that has ever been accused of invading another state’s territory.

Ukraine may succeed in obtaining money from the donor community to support its clean-up, said Weir. ‘This might go in Ukraine’s favour because it has ensured that environmental damage has a really high degree of visibility, and because it’s on Europe’s border,’ he said. .

However, any funding through this route will likely be piecemeal and Ukraine will be left to pay for the rest. ‘There will be a lot of competing priorities post-conflict, such as rebuilding housing and basic services,’ Weir said. ‘That’s where the money will go – not to environmental remediation and clean-up. It’s very likely the impacts we see in Ukraine will last for decades.’

But Weir is encouraged by the growing interest in the issue. ‘There’s a slowly increasing awareness and sensitivity to the environmental dimensions of armed conflicts, which hopefully at some point will translate into policy and behavioural change on the ground to reduce harm and better address it post-conflict.’

The military emissions gap

Very little attention has been paid to greenhouse gases emitted during war, but they’re getting more difficult to ignore. The Conflict and Environment Observatory Unit (CEOBS) has estimated that the military is responsible for 5.5 per cent of global emissions – the equivalent of the fourth-largest national carbon footprint in the world.

As well as the use of military vehicles and weapons, emissions also come from fires and, eventually, reconstruction of destroyed homes and infrastructure.

There’s currently no internationally agreed method to measure and report military greenhouse gas emissions, but according to CEOBS, in 2018, the USA military’s emissions were greater than those of 53 countries combined, while the UK Ministry of Defence accounted for at least half of UK central government’s emissions.

Both the USA and the UK have made commitments to reduce their emissions, but without the means to fully track and report reductions, it won’t be possible to monitor progress. There’s also no formal obligation for any state to report its military emissions to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. However, in 2021, NATO announced that it was developing a methodology to help its members report their greenhouse gas emissions.

Data relating to some key sources of emissions, such as fires and post-conflict reconstruction, were too poor to include in the estimate, meaning the total could be much higher. There’s also limited publicly available data on emissions from military vehicles, bases and industrial supply chains.

A project carried out by CEOBS and the universities of Lancaster and Durham found no year-on-year improvement in the quality of military emissions reporting by governments. Many countries don’t provide any data at all – including some of the top ten military spenders, such as India, Saudi Arabia and South Korea. Emissions had risen among countries that did report, including Australia, Denmark and Italy.

Ukraine estimates the emissions from Russia’s invasion so far as 33 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent from the conflict and 23 MtCO2e from fires. It predicts that reconstruction of infrastructure and buildings destroyed or damaged during the war could emit 49 MtCO2e.