Action on climate change and dealing with the loss of biodiversity are inextricably intertwined, says Marco Magrini

Climatewatch

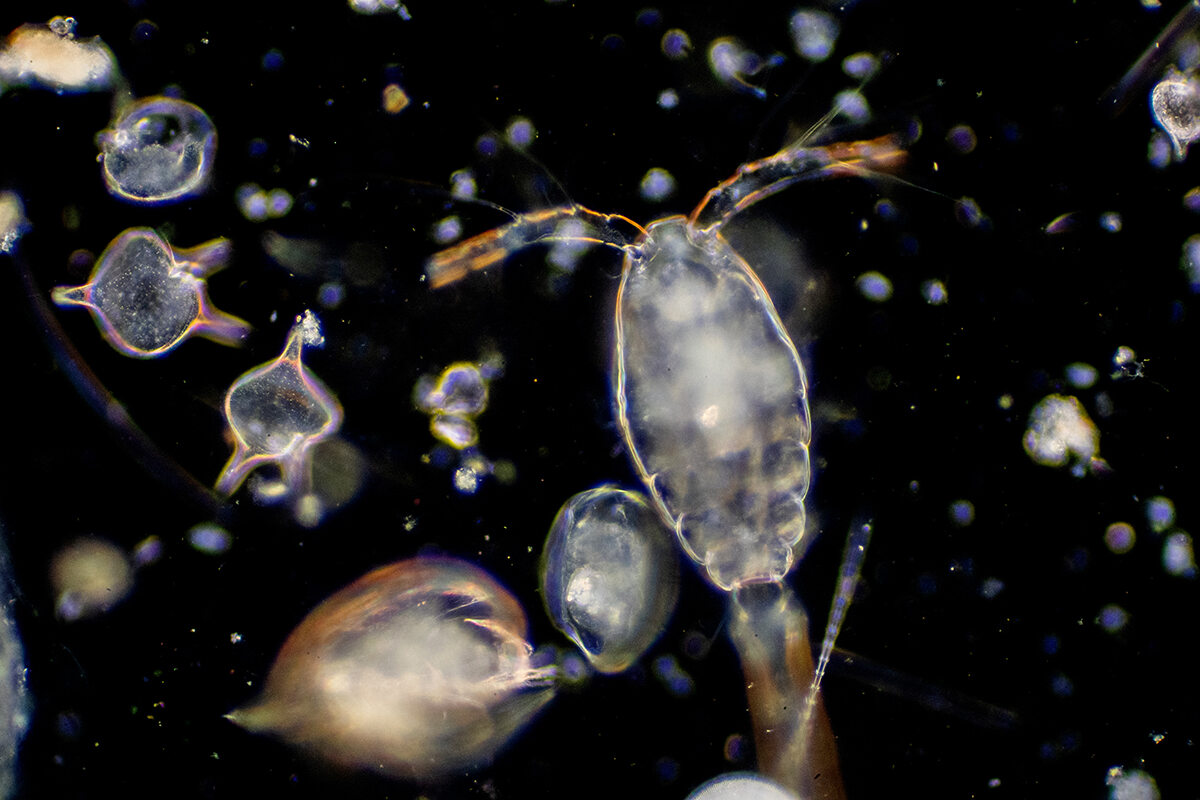

It’s the variety of life on Earth that makes the world go around. From bacteria to whales, from phytoplankton to sequoias, the amazing web of life encompassing the planet generates the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat and a heck of a lot of other things.

However, the menaces hanging over this treasure chest of biodiversity are frightening to say the least.

The UN Biodiversity Conference, COP15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity, to be held in Montreal from 7 to 19 December, will try to patch things up. The summit’s seat is somewhat auspicious. In 1987, in that very place, the Montreal Protocol on protecting the ozone layer was signed – probably the most successful international agreement ever ratified. Yet, it’s ominous at the same time. The conference, originally scheduled to be held in Kunming, China, then postponed four times, will open in Montreal (home of the UN Biodiversity Secretariat) but under a Chinese presidency. Unfortunately, at this time in history, Canada and China are all but friends.

The biodiversity convention was conceived in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio, along with the climate change convention (which held COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, in November). Reversing the climate crisis and reversing the loss of nature should be part of the same effort, as you can’t solve one without solving the other.

MORE CLIMATEWATCH COLUMNS FROM MARCO…

According to WWF’s Living Planet Index, there has been a 69 per cent decline in animal species populations since 1970. More than 70 per cent of the world’s crops depend on pollinators, which are victims of the same decline. Even if we were to halt the immoderate use of fertilisers and pesticides across the globe, or to stop every environmental crime, unbridled warming would still condemn many species to falling over the edge of extinction. Even if fossil fuel emissions were to be halted today, other factors, such as deforestation and plastic pollution, would still be taking a heavy toll on nature.

This month’s Montreal summit has a long list of noble, worthy goals, such as bringing in protection for at least 30 per cent of land and, crucially, oceans by 2030, and halting species extinctions caused by humans. Its outcome, however, depends entirely on the vagaries of diplomacy. Xi Jinping hasn’t invited any country’s leader to the conference, as would be customary. And in the current geopolitical scenario, the summit could easily end up lacking the required momentum.

As if Mother Nature isn’t screaming for help enough!