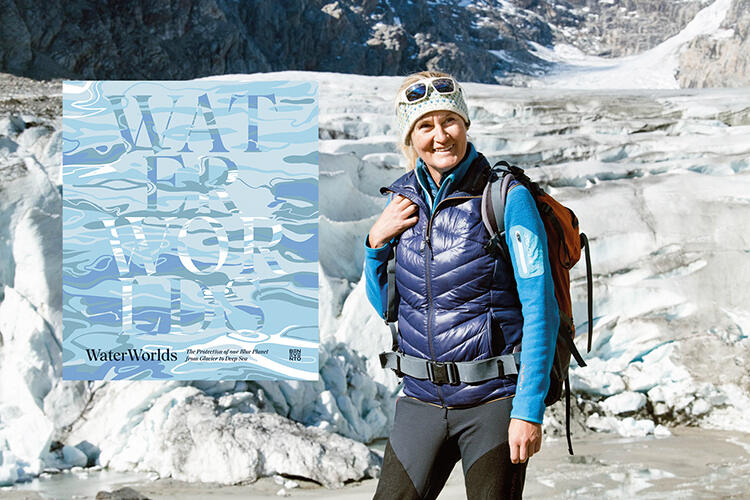

From glaciers in Alaska to Lake Titicaca, Waterworlds profiles the illuminating experiences of 12 people – or ‘waterkeepers’ – fighting to defend our blue planet

It’s hailed as the elixir of life, acclaimed as the most important substance on our planet, covering roughly 70 per cent of the Earth’s surface. We’re talking, obviously, about water. No living creature, from tiny cyanobacteria to giant blue whales, can survive without water, a fact that in an age of global warming we seem to be determined to put to the test. Whether it’s glaciers, rivers, lakes or the great oceans, water’s natural habitats are under threat.

By

This book relates the experiences of 12 people involved in a passionate battle for the preservation of water. From the glaciers of Alaska to the ocean waters of New Zealand, these ‘waterkeepers’ put forward their campaign to defend our blue planet.

Particularly illuminating is the case for the survival of the Earth’s receding glaciers. We look at a glacier and perceive a huge field of ice, but by no means are glaciers lifeless. What Austrian ecologist Birgit Sattler sees is a living body in which one millimetre of meltwater can contain hundreds of thousands of bacteria, algae and fungi. Glaciers are keystones to life on Earth, she explains. Only 0.5 per cent of the world’s water is freshwater and about three-quarters of it is stored in glaciers, meaning that they represent the largest reservoir of freshwater on our planet. Their meltwater runs downstream, nourishing ecosystems and providing billions of people with water to drink and irrigate crops.

Bolivian environmental activist María Eugenia Millares Cahuana considers Lake Titicaca a living being more than a body of water. She recalls her grandmother speaking of lake fish she has never seen in her lifetime, victims of mining and other unsustainable industrial activities along the lake’s shores. Kenyan environmental expert Roniana Adhiambo speaks of the tragic parched shores of Lake Victoria. She spent five years working to make the lake’s polluted waters suitable for fishing and drinking, later moving on to work with a Dutch NGO to capture rainwater and replace native grasses beside a lake in Masai livestock-herding territory.

Scientists estimate that 50–80 per cent of oxygen produced on our planet comes from water. These environmental activists present a compelling case for safeguarding our primary source of life.