Sophie Yeo explores species extinction and environmental loss, highlighting the urgent need for conservation

By

At which point in history did our world cease to be wild? Was it during the Industrial Revolution, a period so transformational that some scientists argue it left a lasting impact on Earth’s geological history? Or did the shift to the tamed and manicured landscapes that surround us today begin much earlier, when humans first picked up tools and began to build fires?

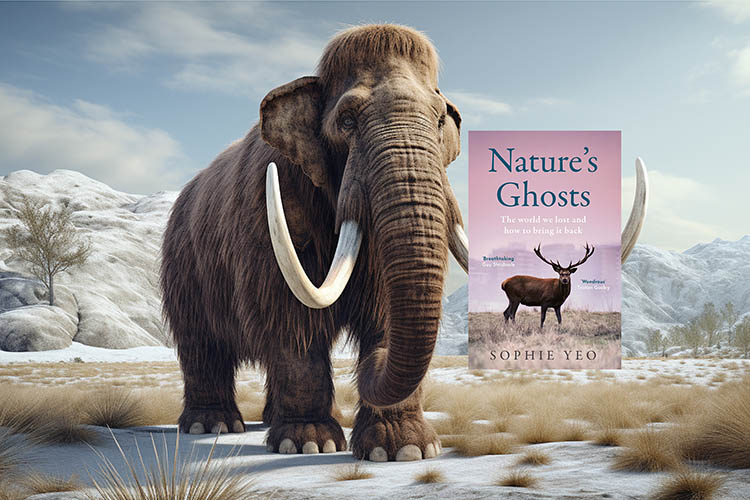

It’s a question that Sophie Yeo ponders in her new book, Nature’s Ghosts, a poignant exploration of how humanity’s actions have shaped the natural world and what can be done to bring some of that old world back.

Most people will be familiar with the concept of ‘rewilding’, a form of ecological restoration that aims to heal damaged ecosystems by minimising human intervention and allowing nature to take the reins (although the term continues to mean different things to different people). Typically, rewilding involves restoring natural processes and reintroducing missing keystone species such as wolves, lynx or bears, which play a critical role in keeping ecosystems balanced. It’s an ambitious approach to conservation that has gained traction in recent years as a way to combat extinction and the effects of climate change.

However, while rewilding’s grand vision of restoring ecosystems to a bygone state can be alluring, critics argue it often gets too bogged down in nostalgia, and that the focus on returning landscapes to a purely wild state overlooks the reality that human societies and ecosystems have been intertwined for millennia.

Others claim that the concept prioritises idealistic visions of pristine wilderness over the needs and livelihoods of existing local communities, a situation that can lead to resentment and hinder the long-term success of environmental restoration projects. But Yeo insists that our options – choosing between a natural or unnatural world – aren’t as binary as they might seem.

Instead, in Nature’s Ghosts, she reveals how letting nature take its course might not always be the best way forward, citing the work historical ecologist George Peterken who suggests that nature can exist on a spectrum. It’s an idea that makes sense when you consider how many times our landscapes have changed and evolved over time. ‘The idea of a natural baseline disintegrates the moment you stop to look at it,’ she adds.

An award-winning environmental journalist and founder of Inkcap Journal – the go-to newsletter for a comprehensive weekly overview of Britain’s conservation news, Yeo is no stranger to the concept of rewilding. She has written about the conflict between residents and wild boar in the New Forest, the poor conditions of Britain’s National Parks and other natural landscapes (which she describes in her book as a ‘skeleton stripped of its flesh’), and has investigated the steps being taken by local councils in their response to the biodiversity crisis across the UK.

Yeo argues that not only do humans have a role to play in the creation of new, wild areas; we may even be vital to them, perhaps even serving as a keystone species ourselves. Small-scale farming which, unlike the current industrial agriculture, can break up the environment and add to the wealth of habitats that exist in a small space, is just one example of what this could possibly look like.

Another is seining, a traditional form of net fishing still practiced in Finland. Yeo explains that by removing fish from the lake, excess nutrients are also taken from the water, helping to maintain the lake’s clarity. It’s a textbook example of how human activities and rewilding initiatives can combine, keeping rural cultures alive while preserving an important habitat.

Throughout Nature’s Ghosts, we visit many of these lost and existing natural words, from the Pleistocene landscapes carved by megafauna, to the eagle-haunted skies of the Dark Ages, to the hay meadows of Transylvania. Yeo reveals in detail how these landscapes have and continue to function, our roles within them, and how they have changed – often, but not always, as a result of our activities.

Along the way, we learn about the work of the palaeoecologists, biologists and anthropologists who are working to piece together a picture of the past from the ghosts that still haunt the land. These ghosts are the echoes of vanished ecosystems and the species we’ve driven to extinction.

Examples include bracken, which is estimated to cover around 1.6 per cent of the UK’s land, and which some ecologists believe grows in areas where Britain’s lost temperate rainforests once grew. Another is pollen records – the remnants of pollen grains trapped in layers of sediment, which have been used to inform the restoration of the ancient forests that once grew in Carrifran Wildwood, Scotland. These ghosts act as clues, Yeo explains, and we should take our cue from them when it comes to conservation.

While there are many proponents of rewilding who would argue that ecosystems possess an inherent resilience and have thrived for billions of years before humans arrived (and that our attempts to control nature has often backfired), we are facing a time of unprecedented ecological collapse. It is our duty, says Yeo, to participate in the restoration of our natural Earth.

It’s here that a knowledge of lost worlds will be most useful. ‘When it comes to restoring the landscape, we can look to the past for inspiration: for what trees to plant, what animals to reintroduce, what ecosystem to target, and so on. By looking even further back in time, however, we uncover a deeper message: that change is strength.’