Solitude, silence and safaris as they once were. Anthony Ham revels in experiencing wildlife without the crowds

We’ve all seen the footage: a cheetah makes a kill out on the savannah and, within seconds, safari vehicles surround it. Or a row of 150 safari vehicles, parked three deep, people out of their vehicles, watch wildebeest cross a river during the Great Migration. I once came upon a lion out on the plains and within five minutes, there were 37 vehicles alongside me, jostling for position – a metaphor for our colonisation of natural places in pursuit of pleasure. I drove away.

The safari is in trouble, many of its icons no longer wild, its relentless quest for a front-row seat on nature’s drama in danger of destroying the very world it seeks to celebrate. It’s a little like going to a concert and finding that the audience is so loud and so numerous that you can barely hear or see the performer. Or worse. Already, in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, studies are revealing the impacts of overtourism on animal behaviour and survival. According to Elena Chelysheva, founder of the Mara-Meru Cheetah Project, cheetahs raise fewer cubs and are less successful in hunting prey in areas of high-density tourism. At one sighting, she counted 67 vehicles.

And I’m part of the problem – part of an industry that sells the notion of the accessible wild, telling people to visit somewhere before everyone else discovers it, adding to the noise, adding to the clamour for that soulful wild encounter without ever stopping long enough to realise that truly wild encounters are, in many places, a thing of the past. I tell myself that tourism can be a force for good – and indeed it can: if no-one were to visit national parks and other protected wild places, many would disappear under the farmer’s crop and livestock’s hoof. But surely there’s a middle path between these two extremes.

I don’t know where the answer to all of this lies, but I suspect that it may be in Botswana. For more than two decades, Botswana has led the way in high-cost, low-density safari tourism. Eschewing the fast money that comes from mass tourism, the country relies on high-end tours and accommodation as the basis for an industry that contributes between nine and 14 per cent of government revenues. Self-drive camping safarisare allowed, but they’re very much the side event, and limited campsite availability helps to keep numbers low.

Botswana is well placed for such a model, having turned what could be disadvantages into positives. For a start, Botswana has the third-lowest population density in Africa (behind Namibia and Libya) – vast empty spaces and a distinct lack of crowding are at the heart of Botswana life. Large swathes of the country, particularly in the Okavango Delta in the north, are inaccessible by road – this means that the best wildlife areas simply don’t have the infrastructure to support mass tourism. And it helps that the country has an alternative source of revenue – Botswana is Africa’s biggest producer of diamonds and the second largest in the world behind Russia. Whatever the reason, going on safari in Botswana is how safaris once were everywhere, but that’s now all too rare almost everywhere else.

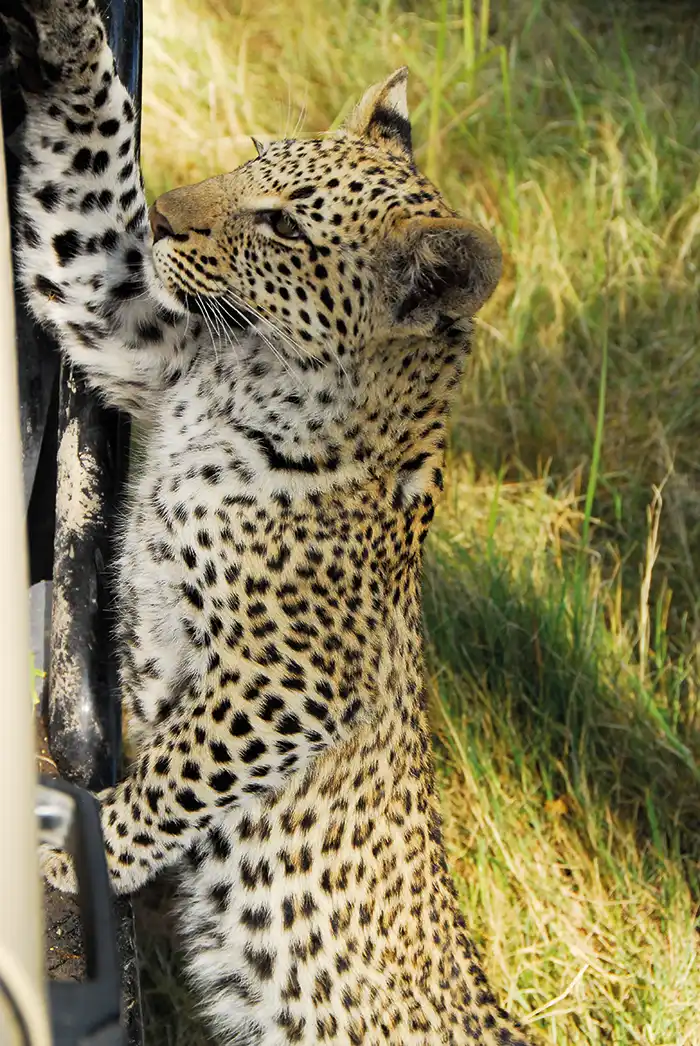

As I flew into the northeastern city of Kasane – where, within an hour of town, Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia converge – I looked out over the vast expanse of uninhabited land and thought back to previous visits. Reliving past sightings in my head, I calculated that during all of my big-cat encounters in Botswana, I had more than 80 per cent of them all to myself, either entirely so (in my rented, self-drive vehicle) or on board the only vehicle in attendance (in a safari vehicle from a safari lodge or tented camp). The lion pride of nine that played and rested right alongside my vehicle in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. The leopard cub that came to my door and stood on its hind legs to investigate the wing mirror while mum, watchful, rested in a dead tree just a few metres away in a remote corner of the delta. The cheetah that streamed across the Kalahari grasslands as if there were nothing to stop it all the way to the far horiz

At Kasane Airport, the team from my luxury tented camp – in this case, Wilderness – took me under their wing, plying me with warmth and hot drinks while we waited for our small plane to depart. I’ve made many similar trips over the years, and I’ve never lost the child-like wonder that grips me as we fly out over Chobe National Park, with its expansive green–blue floodplains, over Savuti with its waterholes surrounded by elephant families, and then over the delta itself – palm-tree islands, glorious waterways the deepest shade of blue, ancient pathways left by millennia of elephants and others moving between the waters.

Touching down at the remote airstrip at Chitabe Concession is like landing on a deserted island that, when water levels are high, in some ways it is. My driver, Gideon, took a hard left and, almost immediately, we were alongside a mother cheetah and her six sub-adult cubs. Gideon had seen them on his way to pick me up and thought I’d like to see them. To see so many cheetahs together was almost as rare as a cheetah mother being able to successfully raise so many cubs to adulthoo

We meandered through classic delta scenery of wetlands, ebony forests and river crossings, all the way into camp. Everything was the height of luxury and good taste, and with only a handful of tents, the footprint was small – the other guests and I had this wilderness to ourselves. Nothing was too much trouble. And yet, of course, I wasn’t paying for any of it. Costs here, as in all high-end camps, run into the thousands, and as a writer for online and print publications, I stayed for free. On one level, it’s the only way I could stay in and write about such places. After all, it’s not like I could drop in for a site visit – there may only be one flight in here a day, and it’s the only way in or out. Aware of the privilege, I am, of course, extremely grateful for their largesse, and conscious that I stay in places for nothing that some people save up for a lifetime to experience.

But I’m never entirely comfortable with the process. Of course, everyone is lovely to me. And of course it’s all wonderful – they wouldn’t show it to me if it weren’t. I can only watch and hope that this is how everyone is treated. I also make clear to those who arrange my trip that I will remain independent, that I shall be fearless in criticism should criticism be needed. And yet, we all know that it will be almost impossible for me to stay in five-star luxury in one of the best wildlife destinations on the planet and then turn around and diss my benefactor.

These are special places, and I like to believe that I would indeed show my independence should standards fall short. But until that happens, we’ll never know. In the meantime, full disclosure is all I can muster while I enjoy what has always been, for me at least, a rather guilty pleasure.

Before dinner, my driver and I ventured out and were rewarded with a pack of wild dogs, 23-strong, that streamed out of the bushlands and across barren plains, pursuing impala. We heard them kill an impala, but by the time we arrived five minutes later, only the hooves and a pair of circling hyenas remained to tell of this poor animal’s fleeting existence upon the Earth.

The next morning, I moved to neighbouring Qorokwe, another superb Wilderness camp, where I spent two joyous hours following a leopard. Then, in the afternoon, I drew near to a lion pride that had colonised a series of termite mounds overlooking a waterhole where elephants came in a steady stream to drink. This was almost unimaginable abundance.

On my tour of Wilderness camps, it’s a recurring theme. Even where there were few major sightings – at lavish King’s Pool, for example, where it was the wrong time of year to be here along a major elephant corridor in the Linyanti Marshes – I still saw lions, zebras and giraffes and, one evening, an elephant caused an evacuation of the dining terrace.

When it came time for them to fly me back to Kasane, everyone seemed surprised that I was continuing my journey by heading out into the wild, alone – just my 4WD camper and me. After so much pampering, I confess that there were moments – when my wheels spun in the sand along the back road to Savuti, when confronted with the prospect of driving across even the smallest expanse of open water – when I longed to be looked after again.

But there really is no freedom quite like this – a bush track, in Africa, never quite knowing when an elephant will appear beside the road.

Past the waterholes and wild dogs of Savuti, skirting the Savuti Marshes, and on into the gathering greens of Khwai, Moremi Game Reserve and the delta.

I thought back to my first solo foray into the delta. Somewhere close to here, possessing an absurd level of trust in my GPS, I ended up circling between waters as dusk drew near, unable to find my way out of the watery labyrinth. Only by backtracking did I return to the path.

Now, two different GPS services took me the wrong way, and it was a paper map that guided me out of the confusion and back onto the right path. Every time I crossed paths with another vehicle – which was rarely – we stopped to chat about track conditions up ahead or to swap the latest sightings. This was word-of-mouth travel: ‘There’s a lion guarding the entrance to Third Bridge’, or, ‘There’s a herd of 300 buffalo up near Xakanaka Lagoon’. I had my own stories to share, of wrong turns taken, of the leopard in the old ebony tree two kilometres back. I have taken these paths before, numerous times, and yet I was struck, as I drove, by the thrilling sense of discovery that again gripped me.

Nearing sunset, I pulled into my campsite. It was low season, so my nearest neighbour was a few hundred metres away; down in the Kalahari, I once slept 50 kilometres from the nearest other human. I cooked dinner on my gas stove, warmed myself by the fire and stared at the stars.

It had been dark for nearly an hour when I sensed movement on the far side of the campfire. It was a leopard. Time stopped. I dared not move, dared not breathe. But I could tell from his movements – his languour, his eyes blinking in the firelight – that he was no threat. He lay down just on the perimeter of the circle of light, not five metres from where I sat, and groomed himself.

In time, my leopard left. Although it was still early, I climbed into the tent on the roof of my vehicle, there to sleep and to listen to the night sounds of wild Africa until first light the next day. Did I long for the comfort of the mattress and the three-course meal with waiter service from just the night before? Perhaps. And yet, there was no place that I’d rather be at that moment in my life. Not all safaris are like this. They should be.