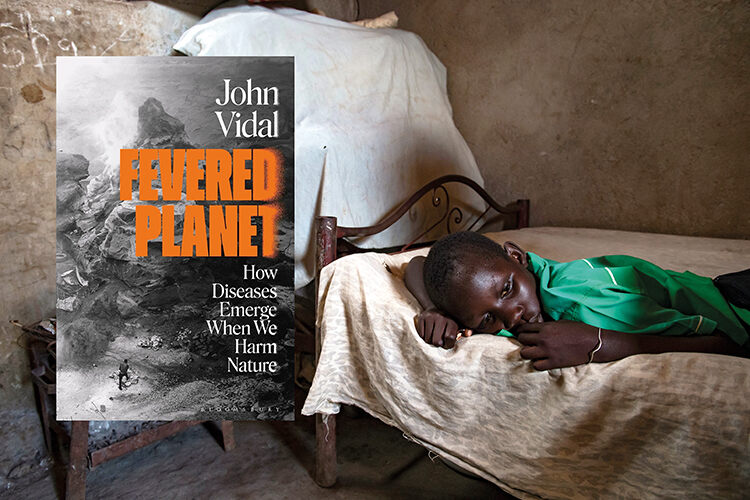

John Vidal, former environment editor for The Guardian, explores the grim connection between emerging deadly diseases and the damage we do to nature

Review by Mark Rowe

Books are always more interesting when someone with a given profile, and who brings certain expectations to their writing, confounds you by penning something different and innovative rather than predictable. Unfortunately, this isn’t that book. The premise is a solid-enough hypothesis: that Covid-19 and many other horrible diseases are emerging and hurting us because of humanity’s relentless, damaging interaction with our environment.

John Vidal’s credentials are impeccable – a former long-term environment editor at the Guardian and a pioneering, determined documenter of our rapacious exploitation of the planet at a time when Fleet Street editors were sneering at such issues. And of course it’s pretty uncontroversial to make the link between logging rainforests, degrading landscapes, global travel and an increasing likelihood of encountering or jump-starting viruses that might otherwise have remained undisturbed.

Persevere with this book, for while the bulk of it reads like a Twitter echo chamber, the latter sections are more solid and analytical. Vidal is better when less preachy and he soberly documents the debate over the origins of Covid-19 – wet market or lab leak? – and writes insightfully about the issues surrounding bushmeat, which has been lazily promulgated as the source of many viruses. That bushmeat can be ‘a vital source of protein… often the only way people can earn money for medicines or to send children to school’ are points often overlooked. The issue, he argues with some force, isn’t bushmeat per se, but whether the meat originates from a healthy animal. This leads Vidal to branch out into a wider surveying view of the way we treat livestock, of how intensive farming of animals and related forest clearance can expose us to disease.

There are solutions and uplifting stories in this book, but will people stick with it to the end to read them? The example of a two-hectare permaculture farm in Malawi is fascinating. There, an American couple created a virtuous circle, improving soil fertility and the diversity of agricultural crops, which in turn leads to better nutrition and stronger immune systems; their Malawian protégé rolled the scheme out further. Nature, Vidal writes, is ‘infinitely resilient and well able to recover from almost any human abuse… humans are amazingly powerful ecosystem engineers’.

What precedes this, however, often feels tiresomely negative and misjudged, an omnipresent, disapproving tone undermining a strong central argument. The first six sentences in the introduction alone contain the phrases ‘deadly viral disease’, ‘deadliest virus’ and ‘mystery and terror’, helping to establish a hyperventilating prose tone that becomes simply exhausting.

Humans, he suggests, were living happily and healthily for 200,000 years in a land of milk and honey but then, bafflingly, we switched to a narrower range of crops and managing animals. Diets became less varied, disease increased, sedentary people manipulated the environment and created the space for new pathogens to thrive. Vidal quotes the late biologist Thomas Lovejoy: ‘We humans did this [Covid-19] to ourselves. A new pandemic, to which we have no immunity, will emerge within a few years.’ You’re left with the inference that humans are innately feckless.

Vidal would help his case if he stuck to facts. The issue is grave enough without jazzing things up or making statements that are simply untrue. Contrary to Vidal’s claims, neither monkeypox nor Ebola were declared pandemics by the World Health Organization; both fell short of meeting even the loosest definition of the term. It’s difficult enough for reasonable people to bat back the flat-Earthers when one of their most effective, manipulating claims – ‘You’re scaremongering!’ – leaps out from a book such as this, with the false implication that monkeypox and Ebola were global-health catastrophes on the scale of Covid-19.

The same misleading claim appears on the book jacket and points to a surprising lack of erudition on the part of a publisher that one would have thought would know better. These errors feel part of a piece; Vidal claims that ‘in quick succession, at least 30 diseases have emerged since the 1990s’. Yet some of those he cites have been around far longer. At different points in the book Ebola and Lassa fever originate in ancient times, the 1960s or the 1990s. Why exaggerate? Either a smaller number or a longer timescale make a strong enough case.

Too often Vidal appears to marinate in conjecture and phrases indicative of muddy thinking, such as ‘possibly’, ‘probably’, ‘probably only a matter of time’, ‘what may be happening, the thinking goes…’, turn up too often for comfort. This panting hyperbole can almost lead the reader to give up barely a third of the way through.

Climate change’s multiplier effect means that things are getting riskier. Malaria and dengue ramp up after rainfall; as extreme weather becomes more common, so too will these and other diseases. There’s an irony that some areas where climate change has been politically highjacked as a myth, such as Florida, are so exposed not just to the baked-in sea-level rises but to the spread of dengue and even malaria. But don’t gloat. ‘There will be no escape,’ writes Vidal, ‘everyone will experience the health effects, whether heat, infections or storms.’

With 238 pages of tub-thumping examples of the harm we’ve done, of doom and gloom, and just 50 rather more upbeat pages, the whole thing just feels lopsided, as if the publisher advised the writer to crowbar in some positivity after reading the first draft. You can bash a chain smoker, a drug addict over the head as much as you like, tell them they’re getting the comeuppance they deserve, but unless you offer people some hope, why should they bother to listen, to change? Why should they expect their governments to bother?