In the Ethiopian highlands, an elusive wolf species has been driven nearly to extinction by war, disease and an ever-burgeoning human population

Words and images by

As the first rays of morning light streak across the frozen gorse and heather, and in the heavens, 100,000 stars fade from view, a sudden movement catches my eye. A large creature with a reputation as dark as the moorland night moves with unnerving speed and silence over this bleak, high-altitude landscape. Pausing for just a second, it turns its head toward me and I catch a fleeting glimpse of sharp ears, hard eyes, and a bushy tail dipped in black, and then the ghost of the highlands turns and continues its silent race against the rising daylight. My encounter with a wolf is over.

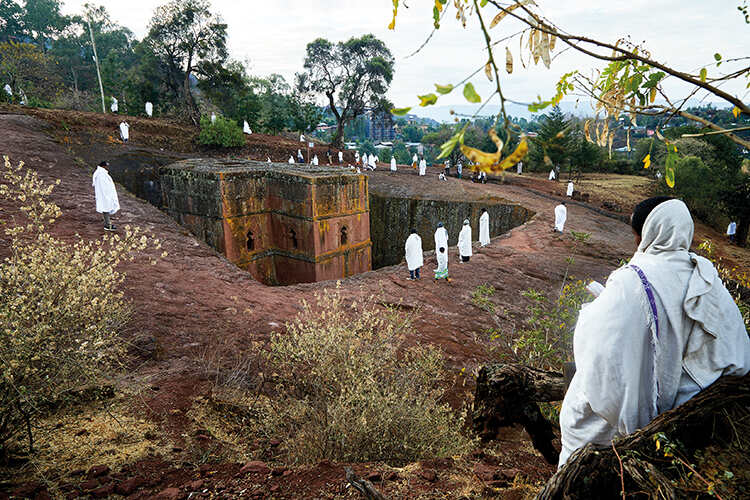

I’m on the mountainous plateau of northern Ethiopia. Rearing up above me like a giant arrowhead is Mount Abuna Yosef (4,260 metres), the biggest mountain in the vicinity and the sixth biggest in Ethiopia. Looking the other way, downwards and off the escarpment, I can just about make out the holy town and major Orthodox Christian pilgrimage centre of Lalibela, where 11 spectacular churches were carved into solid rock during the 12th century with the help, so the legend goes, of a team of angels.

Although my reasons for coming to this far corner of Ethiopia aren’t religious, there’s a certain element of pilgrimage to my journey. I’m here to search for the elusive Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis). It’s a creature so rare that some might say that you have more chance of spying an angel.

Despite the name, the Ethiopian wolf is not the big, bad wolf of folk stories. In fact, with its slender, delicate frame, long legs and shortly cropped coat, the Ethiopian wolf looks more like a fox or jackal than a fairy tale wolf (indeed, it’s sometimes called the Simien fox or Simien jackal). And Dessiew Gelaw, the guide who’s assisting me in my search for wolves, assures me that the Ethiopian wolf poses no threat whatsoever to people.

Dessiew is from the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme (EWCP), an NGO charged with protecting the Ethiopian wolf population and its habitats. Having assured me that this wolf doesn’t have teeth that are all the better for eating me, he goes on to tell me that we were lucky to have had even that briefest of encounters with an Ethiopian wolf. ‘This area was a frontline during the recent civil war,’ he says. ‘Soldiers from both sides crossed over this plateau several times. I don’t know what went on up here then because it got too dangerous for me to stay, but ever since then, the wolves have been harder to see. Before the war, I used to see groups of five or six almost every day. Now, though, on a good day I might see one or two.’

Personally, I felt privileged to have had even the most fleeting of glimpses of a solitary Ethiopian wolf because, with only around 500 of them remaining, the species has the unfortunate distinction of being one of the rarest canines on Earth.

With the sun now blazing, Dessiew, his assistants, and I return to the stone cabins (which were partially destroyed during the war) that currently served as home base for Dessiew and his team. As we walked over the moorland, I asked if this lack of recent wolf sightings meant that the wolves had been shot by soldiers during the war. ‘I don’t think so,’ Dessiew replies. ‘Instead, the wolves all seem to have gone down lower into the valleys. Maybe it was because they were disturbed so much by the soldiers but maybe it’s also because they have been attracted there by all the rodents feeding on crops around the farms. At the moment, we just don’t know. But, whatever the reason, the wolves’ presence so close to people is starting to cause conflict because the farmers blame the wolves for eating lambs. It’s unlikely, though, that wolves are attacking livestock because they normally eat giant mole rats and other rodents. The real culprit is more likely to be jackals. Fortunately, though, most of the time, this conflict is just people chasing the wolves away rather than actually killing them.’

Dessiew tells me that there are three distinct packs of wolves in the Abuna Yosef region, with a total population of around 28–32 wolves. ‘These wolves only live in certain parts of the Ethiopian mountains and nowhere else on Earth, so this habitat is critically important to them,’ he says. As well as the Abuna Yosef population, other wolf hotspots include the Menz-Guassa Community Conservation Area to the northeast of the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, where a population of around 25–30 wolves ekes out an existence and, in the south of Ethiopia, the Bale Mountains, which, with 200–300 wolves, is the stronghold of the species. It’s there that I head next.

At around four kilometres above sea level, the cold, thin, oxygen-depleted air of the Sanetti Plateau, a vast Afro-alpine moorland that makes up the heart of the Bale Mountains, burns the back of the throat and my breathing is laboured. But the minor hardship is worth it because here the wolves are much easier to spot and, on just my first morning, I locate a group of four wolves playfully chasing one another across the grasslands in the dawn sun.

The Sanetti Plateau might be the last stronghold of the Ethiopian wolf but that doesn’t mean guaranteed safety. As with any isolated animal population, a single bit of bad luck could spell the end of the road for the wolves. And on the Sanetti Plateau, bad luck comes in the form of the domestic dogs that wander up from fringing villages. With depressing frequency, these dogs bring diseases such as rabies and canine distemper. According to the EWCP, there have been at least eight major disease outbreaks since 1992 among the wolves of the Bale Mountains and some of these outbreaks have resulted in significant population crashes.

But, there is hope. The EWCP is working hard to vaccinate both domestic dogs living near wolf country and the wolves themselves. By 2025, it aims to have vaccinated 40 per cent of wolves in each population group in Ethiopia and 70 per cent of dogs living in and around the Bale Mountains, and to have reduced by half the number of free-roaming dogs in the mountains.

However, disease might not be the biggest threat to the future of the Ethiopian wolf. Instead, it’s a problem that’s likely to be much more difficult to fix.

To find out more, I head back to Addis Ababa to meet Eric Bedin, a field director from the EWCP, at a central cafe. Sipping richly scented Ethiopian coffee, Eric, who hails from the French Pyrenees but has spent many years studying wolves in Ethiopia and is one of the leading authorities on the species, tells me that the biggest threat to the wolves comes from habitat loss. ‘Ethiopia’s human population is growing fast (the current annual growth rate stands at 2.6 per cent) and all these extra people need somewhere to live and food to eat,’ he says. ‘Inevitably, this means more encroachment into wolf country and the areas around it. The wolf populations here are now living on moorland islands surrounded by people and agricultural land.

‘The EWCP works with communities in areas where wolves live to increase awareness of the wolves, to dispel myths about them attacking livestock and to explain how people and wolves can live together,’ he continues. ‘Although most of the current wolf habitat is now under some form of official or community protection, the overall wolf population in Ethiopia has continued to slowly drop as the habitat becomes more and more degraded.’

On paper, the future for Ethiopia’s wolves might seem touch and go, but there is some hope. Unlike in many parts of the world where predators are being hounded out by humans, in Ethiopia, this is less common. ‘Sure,’ Eric says, ‘wolves are sometimes blamed for attacking lambs and farmers and shepherds will chase wolves away, but people rarely go out of their way to kill a wolf.’

His words made me think of something that Dessiew had said as we’d descended from Abuna Yosef. They were words filled with pride and hope. ‘When I was a child, I hated the wolves because they attacked my family’s sheep,’ he told me. ‘But when I learnt how rare the wolves were and that they lived only in Ethiopia, my attitude to them changed. Now, every time I see a wolf, it refreshes me, it excites me. The wolf is my life.’

Then, pausing for a moment, Dessiew looked me in the eye with the intensity of a wolf. ‘For me’, he went on, ‘the wolf is Ethiopia’.

If you go

To learn more about Ethiopian wolves, visit the EWCP’s website at ethiopianwolf.org. Ethiopian Airlines flies daily from Addis Ababa to Lalibela, the nearest town and airport to Abuna Yosef, and thrice weekly to Goba, close to the Bale Mountains. Tesfa Tours (tesfatours.com) and Nashulai Journeys (nashulaijourneys.com), which both work closely with local communities and conservation projects, run trekking tours that incorporate visits to Abuna Yosef and other wolf habitats.