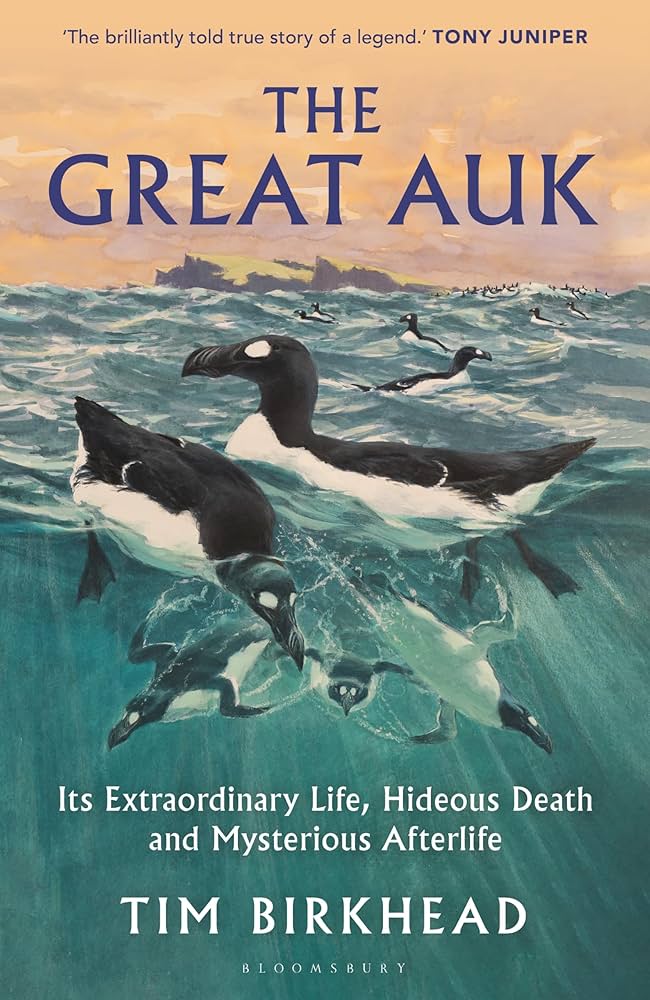

Tim Birkhead on great auks and their extraordinary story of evolution, exploitation and de-extinction across the years

Around 1800, as the scientific study of birds came of age, the need for specimens to study, including skins and eggs, became an obsession among ornithologists.

Reference collections would provide the foundation on which the discipline of ornithology was to be built. Without a clear idea of how different species were related to each other (phylogeny) there could be no progress. But in the days before there were national museums, the accumulation of bird species was largely down to private, wealthy individuals.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

Inevitably, scarcity bred desire among collectors and no sooner had it become known that the once-numerous great auk, a large, flightless bird, was becoming scarce, than the final countdown to its extinction began.

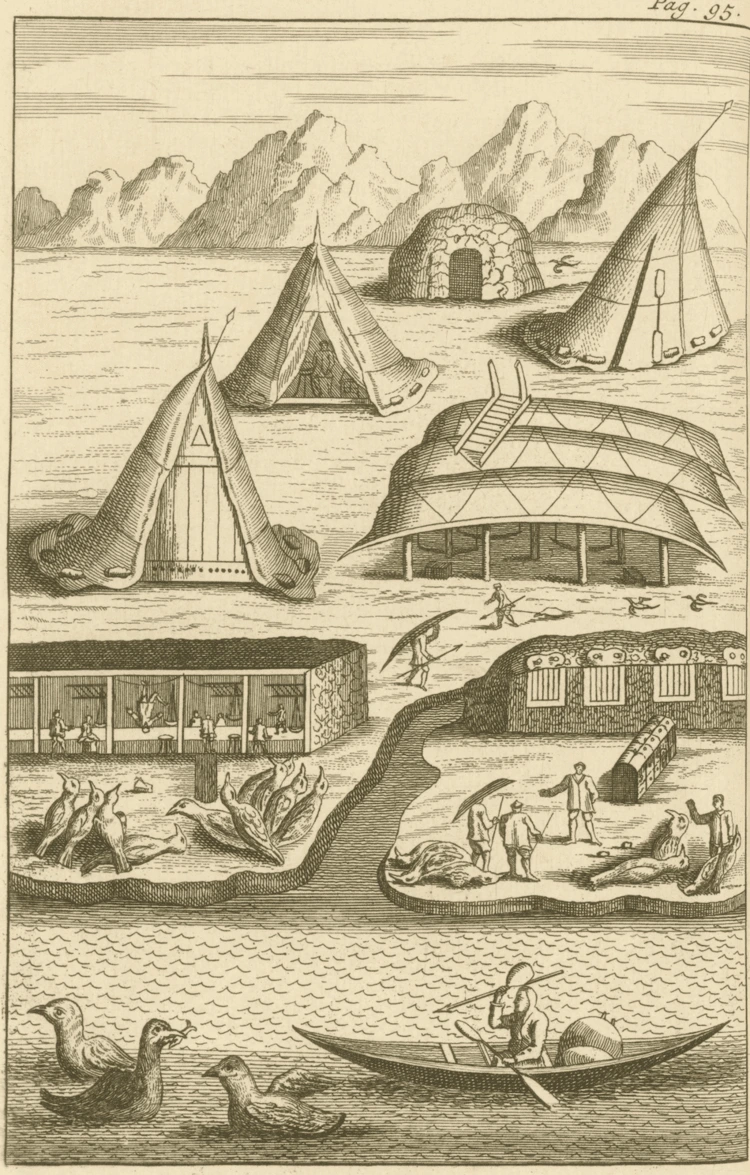

Once hugely abundant on Funk Island and in the surrounding Newfoundland waters, the region’s great auks were finished off by 1800 in the quest for meat, fat and feathers – with barely a single specimen collected. The only remaining birds – also a remnant of a once much larger population – were those in southwest Iceland.

Word got around and soon the dealers – mainly from Denmark – were swarming like flies around a beast about to die, encouraging poor farmers and fishermen to make the perilous journey out to the birds’ breeding grounds on the Reykjanes Peninsula. By 1844, the great auk was extinct.

Like many other members of the auk family (the Alcidae), great auks bred in colonies, favouring remote offshore islands safe from terrestrial predators such as polar bears and foxes. The colony on Funk Island was huge, probably comprising hundreds of thousands of pairs, which, like their auk cousins, each returned to the same tiny spot to breed each year. Great auks were socially monogamous, and like most auks and other seabirds, probably re-paired with the same partner

year after year.

They will have exhibited what’s called deferred reproduction, not breeding until perhaps they were six, seven or eight years old, but then continuing to breed for decades and living (if undisturbed) for as long as 50 years. Like many other seabirds, the great auk laid and incubated a single egg, with the father taking the chick to sea at around three weeks of age and then caring for it for a few further weeks at sea – just as common guillemots and razorbills do.

The great auk’s egg is ‘pyriform’ in shape (like that of the guillemot), an adaptation to being incubated on bare rock with no nest, where that particular shape provides the egg with greater stability than any other. Like the guillemot, the great auk bred shoulder to shoulder with its neighbours, as attested by William Taverner, who in 1718, visited Funk Island and reported that the birds bred so close together it was impossible to place one’s foot between the eggs.

Losing the ability to fly seems like a very extreme adaptation, but together with its greater size (around 3.5 kilograms) than its extant cousins, meant that the great auk was an excellent underwater predator – essentially the ‘penguin of the north’. Great auks evolved in the absence of humans, but the emergence of humans meant that the great auk’s flightlessness rendered the bird desperately vulnerable at their breeding colonies. Human hunters, with only a modicum of agility and nous, could run them down.

Most of the great auks killed in eastern North America before they disappeared in around 1800, were either eaten or, more often, stripped of their feathers to stuff mattresses. Those killed in their last surviving stronghold in southwest Iceland from the late 1700s, were taken as scientific specimens.

Their corpses were ferried back to Iceland’s mainland, where they were skinned by local women, and their flaccid skins packed up and sent to Copenhagen, where dealers and museum men had a virtual monopoly.

It was only then in the early 1800s that the reconstruction process could begin, for the taxidermists’ job was – ironically – to recreate a lifelike image of the once-living bird, which of course they had never seen alive. Indeed, very few educated men ever saw the great auk in its natural state, and none, I think, were able to watch the bird undisturbed by human killers.

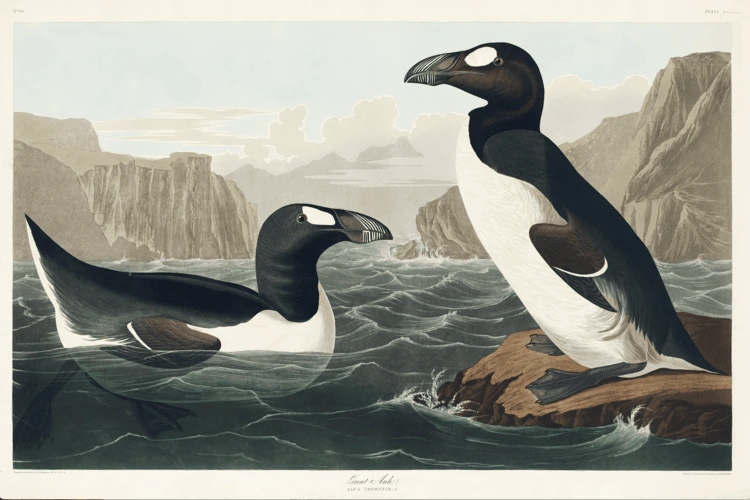

Some 78 great auk mounted specimens exist, now mostly in museums across the world, and looking at their images, it’s easy to see how hard most taxidermists found it to produce a lifelike replica, for many of the specimens are too thin, too fat, or poorly postured.

For the majority of people looking at such specimens, it hardly mattered, because they too had never seen the real thing and hence had nothing to compare with. But for the minority, with knowledge of the great auk’s relatives, guillemots and razorbills, they had a very good idea of how the great auk must have looked. Of all the known specimens, few are genuinely lifelike.

Artists drawing, engraving or painting great auk images suffered the same reconstruction difficulties, evidenced by many dreadful illustrations. Part of the problem is that members of the auk family have wonderfully subtle conformations comprising smooth, sleek bodies topped by oddly shaped beaks, for underwater pursuit and display.

The laterally compressed, colourful beaks and facial ornaments of Atlantic puffins seemed to have been a particular artistic challenge, and in the same way, the large white spot in front of the great auk’s eye – a different kind of facial ornament – constituted a special problem, with some artists thinking the eye lay within it, others positioning it, or the eye itself, in an inappropriate, anatomically impossible location on the bird’s head, creating an inappropriate and – to me at least – an unconvincing re-construction.

Charles Darwin was among the first biologists to employ what is now known as the ‘comparative method’ to make inferences about how a particular species evolved.

It’s an approach based on the assumption that organisms that have evolved from a common ancestor will share many traits and it has allowed us to reconstruct much of the great auk’s ecology and behaviour.

Ornithologists long recognised from its overall appearance that the garefowl – as the great auk was once known – was a kind if auk, related to the physically similar but smaller razorbill – previously known simply as the auk or the razorbilled auk, to distinguish it from the even smaller little auk.

It was Thomas Pennant, Gilbert White’s correspondent, who in 1776, christened the great auk with its present name. Prior to this, the species was known as pitiguoen by predatory Portuguese 16th-century mariners. That became ‘penguin’, long before real penguins were discovered. When they were, it was assumed, by some at least, that great auks and penguins were relatives with a common ancestor. As anatomical studies showed, they most certainly weren’t, but instead provided a compelling example of unrelated species evolving in similar ways in response to similar environments – a phenomenon known as convergent evolution.

It was by using anatomical and morphological comparisons that early taxonomists, including ornithologists, inferred evolutionary relationships between species, but convergent evolution meant that this method was far from foolproof.

The development of molecular techniques, starting in the late 20th-century, sidestepped that particular issue, and by the early 2000s, it was confirmed that the great auk’s closest cousin was the razorbill and the two guillemot (murre) Uria species, providing biologists with a much more secure foundation for reconstructing the great auk’s lifestyle.

Reconstructions of previous cultures, of language, of dinosaur biology, are made more difficult by false leads. In the great auk’s case, the potential for human error creating false leads has been a crucial factor in the bird’s reconstruction, because most of those who saw great auks alive weren’t scientists or ornithologists, but seamen, farmers and fishermen intent only on killing them.

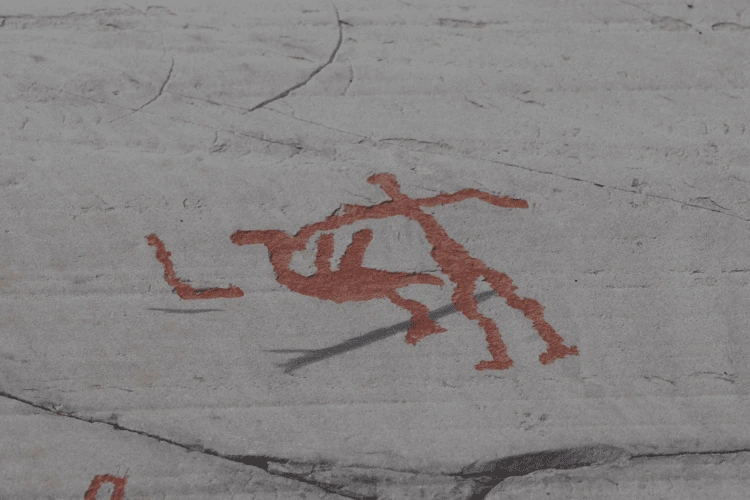

This in turn allowed subsequent authors to let their imaginations run free, and many early images show the great auk perched on ice floes, suggesting that this was a bird of the high Arctic. It wasn’t, as the 19th- century Danish professor Japetus Steenstrup showed, by plotting the location of all great auk remains; the great auk was a bird of boreal waters.

A second example of a false lead involves Scottish folk hero Martin Martin who, encouraged by the Royal Society, visited St Kilda in 1697 to document the lives of Britain’s own primitive peoples, whose economy was dependent on the huge numbers of seabirds that bred there.

Although the great auk no longer bred on St Kilda, the residents Martin spoke to were able to tell him about the bird’s biology, which Martin duly recounted in his Late Voyage to St Kilda, published in 1698, which for centuries has been assumed to be factually correct.

Unfortunately for Martin’s fans, it isn’t; his account contains several incorrect ‘facts’. A single example will suffice. Martin tells us that the great auk had but a single brood patch upon its breast – that is, the area of bare skin against which a bird warms its eggs during incubation.

No-one challenged Martin’s statement, possibly because it was known that the guillemot has a single brood patch, even though the razorbill has two, one under each wing (but incubates only a single egg). It seemed odd to me that the great auk should possess a single brood patch, if its closest relative – the razorbill has two.

With the help of some colleagues, we examined a number of great auk specimens housed in German natural history museums, and in all cases, the birds were found to possess two brood patches. A minor triumph you might think, but an important brick in the reconstruction wall. And knowing that the great auk had two brood patches tells us that it incubated in a horizontal posture (like a razorbill) and thus occupied more space than it would if it adopted the semi-upright posture of the incubating guillemot, and hence altering how we estimate the amount of space its breeding colonies would have occupied, and in turn its population size.

The reconstruction process continues. It’s now possible to extract mitochondrial DNA of sufficient quality from both relatively recent (170 years) to quite old (15,000 years) great auk tissue and bones. This in turn has allowed researchers to reconstruct the great auk’s population dynamics and, crucially, to judge whether its extinction was the result of natural causes such as climate change (as has been suggested), or human persecution.

The study assumed, as has been verified in other research, that evidence for extinction by natural causes would be provided by a gradual reduction in the variation in mtDNA over time. If persecution was the cause, however, no such reduction would be apparent. And, as I expected, it was of course, the latter: humans had exterminated the great auk.

Molecular advances mean that hovering on the horizon is an additional and tantalising reconstruction opportunity: de-extinction. Over the years, several ornithologists and writers that I know, as well as myself, have tried to imagine what it would be like to come across a hitherto unknown colony of great auks, a discovery that would simultaneously be both exciting and problematic. The cause for excitement is obvious, but the problem would be whether to keep the discovery a secret or tell the world, for telling the world would put the birds in danger of collectors once again.

The issue is perhaps of theoretical interest only, for it is now 180 years since the bird was rendered extinct and the chances of finding any birds alive is nil. However, the de-extinction of the great auk through molecular magic would create a similar kind of moral dilemma. On the one hand it would be tremendously exciting to see and study this iconic bird, allowing us to check whether our assumptions about how it lived have been correct.

On the other, would it be morally appropriate to bring back to life a bird whose present cousins and more distant relatives – other seabirds – are facing unprecedented anthropogenic challenges and declining numbers? Climate change, over-fishing and bird flu and other threats have resulted in seabird numbers worldwide falling by more than half in the last 70 years. The great auk’s de-extinction is some way off, so in once sense, we have time to ponder whether it’s morally right or not.

In the meantime, continued access to and examination of the existing great auk relics, including its DNA can only help us improve and refine our understanding this iconic species’ biology.

Tim Birkhead is emeritus professor of zoology at the University of Sheffield. He has studied auks for more than 50 years.