Helen Scales talks about her latest book, Around the Ocean in 80 Fish & Other Sea Life, the blue economy and our complex relationship with marine life

Words by Bryony Cottam, Illustrations by Marcel George

The European eel, Anguilla anguilla, is a mysterious fish. Until recently, it thrived in lakes, estuaries, rivers and streams across Europe and northern Africa. It has always been a popular food, first for the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, and today it can be found jellied in London, grilled in Italy and smoked in Sweden. In medieval England, writes British marine biologist Helen Scales, eels were an important part of the economy – a cheap food for the masses. They were even used to pay taxes and rent. ‘There is a very long history of humans using eels,’ she says. Yet for a very long time, nobody knew where they came from.

It was only last year that scientists finally found concrete evidence of where eels go to breed – the Sargasso Sea, a remote region of the North Atlantic Ocean. ‘To me, the eel is a wonderful symbol of how our lives are connected to these very distant parts of the ocean,’ says Scales, whose new illustrated book, Around the Ocean in 80 Fish & Other Sea Life, reveals many of the surprising ways in which the lives of humans and marine species are intertwined.

From the surprising beauty of nudibranchs (sea slugs) to the unexpected diversity of British marine species, Scales’s book is a relatively brief tour of the vast and often little-understood array of life below the waves. ‘I tried to pick out species that show the really rich connections between humans and oceans,’ she says. ‘There are lots of ways that marine life has been incredibly useful for us, for humanity. We’ve gained an awful lot of really powerful tools from the ocean.’

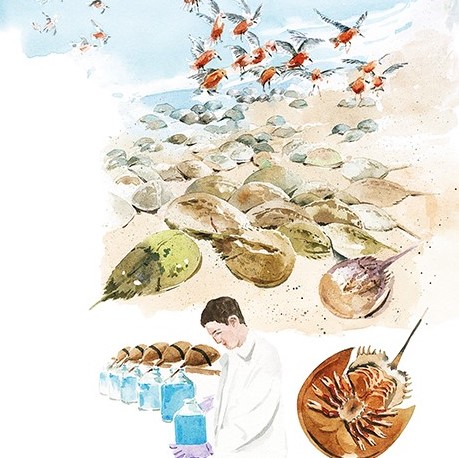

One such example is the Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus), a ‘living fossil’ that has existed nearly unchanged for more than 400 million years – long before dinosaurs first roamed the Earth. ‘Most humans alive today have had a potentially lifesaving encounter with the blood of a horseshoe crab,’ says Scales. Their bright-blue blood contains powerful immune cells that are highly sensitive to toxins made by bacteria and are used to test the safety of new medicines, such as vaccines, surgical equipment and medical implants.

Others include some of the 700-odd species of deadly cone snail (Conidae) – a favourite among shell collectors, who prize them for their pretty patterns – whose powerful toxins have inspired new drugs for AIDS, Covid-19 and malaria; and the bioluminescent crystal jellyfish (Aequorea victoria), which produces a fluorescent protein that Scales says has helped revolutionise the way in which we study genes, cells and diseases. She’s quick to point out, however, the extent to which many of these much-valued species (and many more besides) are now at risk.

‘European eels in particular are in a terrible state,’ says Scales. Habitat loss, pollution, barriers on inland waterways and a growing trade in illegally exported juvenile eels have all pushed the endangered species towards extinction. Between October 2022 and June this year, European police made more than 250 arrests and recovered 25 tonnes of trafficked live baby eels (known as elvers or ‘glass eels’) worth around €13 million that were destined for fish farms in Asia. It’s estimated that European eel populations have declined by up to 90 per cent since the 1980s. ‘I think that’s testament to how human activities have really shifted into a different gear in recent years,’ she says. ‘We’ve had centuries of exploiting eels and eating them, and they carried on existing. It’s only in recent times that we’ve reached a point where their continued existence is rather precarious.’

For a long time now, we’ve relied heavily on the oceans for our food, but also for our energy, transport and livelihoods. More than 90 per cent of all goods are transported across the sea and ocean industries – fishing, shipping and marine tourism – contribute more than US$1.5 trillion to the global economy. As Scales puts it, we’re guilty of acting ‘as if [the oceans] were an infinite store cupboard’. Spoiler alert: they aren’t. The intensification and expansion of human activities has had an impact and we’re starting to see that the oceans can indeed fail. Fishing, mining and shipping, as well as tourism, pollution and climate change, are all taking their toll.

It’s perhaps unsurprising, considering that an estimated 80 per cent of our oceans are yet to be explored, that much remains unknown about the species that live in them, including the ones that we value and use. We still don’t know exactly how eels reproduce after their long migration to the Sargasso Sea, and recent studies have revealed that as many as one in three Atlantic horseshoe crabs – which were formerly assumed to survive being bled while alive – actually die after being released. ‘One of the weird examples I like from the book is the smooth handfish, this little species down in Tasmania that was the first fish to be declared extinct in modern times. Then, just 18 months later, it was declared that it might not be extinct – because maybe it’s still out there, somewhere,’ says Scales. ‘For me, that really sums up just how hard it is to definitely know what’s happening in our oceans.’

Scales says we’re now in a ‘golden age’ of ocean discovery, with the technology to open up deeper and less accessible places than ever before. At the same time, changes are happening orders of magnitude faster in the oceans than they are on land. ‘We really are playing catch up, not just in terms of understanding what the ocean was like a few decades ago, but how it’s changing now.’ That makes it very difficult to know exactly how marine life will be affected by our growing presence, particularly in the deepest oceans. Scales points to the scaly-foot snail (Chrysomallon squamiferum), the first species to be officially listed as endangered simply due to the potential threat of deep sea mining, a topic she says she has been amazed to finally see in the news. ‘It’s been years and years in the making,’ she says. ‘And finally, people are paying attention.’

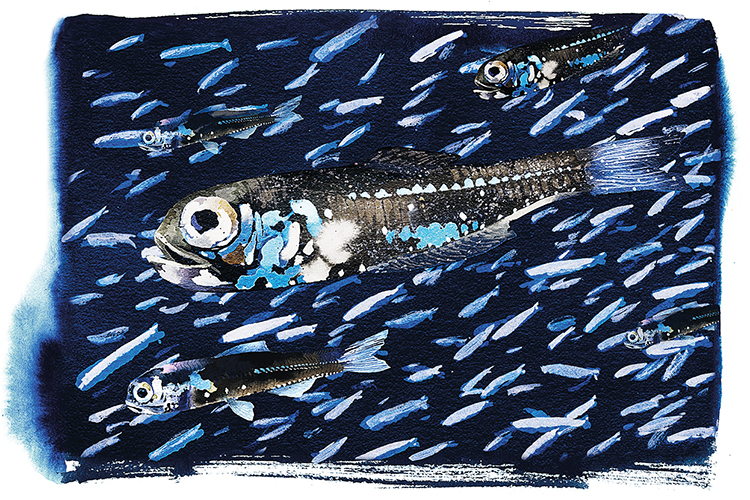

Meanwhile, mesopelagic species such as lanternfish (Myctophidae) that inhabit the ocean’s twilight zone are one of the next big issues in marine conservation. So far, these deep-sea fish have been mostly ignored by commercial fishing – but that could soon change. ‘There are plenty of reasons to predict that those species living in harsh and challenging conditions in deeper oceans will be less resilient to exploitation,’ Scales says. ‘Their lifespans are often very long and they typically have slower growth rates. It’s likely going to be sensible to leave them alone. Sadly, humanity has a terrible track record of over-exploiting species in the more accessible parts of the ocean. It would be naive to assume that we would do it any differently in the deeper, less accessible parts.’

All this excitement about the ocean’s potential – often called the ‘blue economy’ – is causing what Scales calls a rush for resources. ‘All these different industries, whether it’s fishing, minerals, renewable energy or even conservation, are all trying to grab bits of the ocean for one thing or another.’ That said, there are ways that Scales believes humanity can benefit from ocean extraction, while keeping marine ecosystems intact. ‘First, the ocean does have the capacity to sustainably feed a lot of people. We just need to focus on a shift away from industrial fishing for wealthy nations and towards feeding people for whom seafood is a really critical part of their diet.

‘Second, we need to ask ourselves: what do we want? Do we want to allow a small subset of corporations to carry on making tonnes of money from mining? Or do we potentially want to find more lifesaving species in the deep ocean, because they live in the same places that are being exploited.’ For Scales, it’s a zero-sum game.

‘I think there is a much greater potential for a much wider part of humanity to benefit from things like bio-exploration programmes, which are looking for unique, complex and biologically active molecules in organisms all through the ocean, but especially in the deep sea. There’s a weird chemistry cupboard down there, full of stuff that doesn’t happen anywhere else, and we need that for new antibiotics, for treatments for all sorts of human conditions.’

If, one day, we really do need to mine the deep oceans, she says, then we’ll go there, but hopefully, we won’t. ‘We should be able to sustainably manage the shallow seas. We’re just not doing it at the moment for political and economic reasons, not for scientific ones. So how about we leave the deep alone and work on that first?’