Virtual experiences are breaking down barriers to fieldwork. And their benefits are being extended to all students

By

Fieldwork is an integral part of geography, earth and environmental science (GEES) degree programmes, but for many, it represents a barrier to university study. In an attempt to make courses more inclusive, some universities are now turning to digital alternatives.

Virtual fieldwork isn’t a new concept – it has been used in different iterations since the early 2000s. However, as the technology has progressed to become more immersive and interactive, these virtual experiences are increasingly able to replicate elements of an outdoor field trip. For geologists Juliet Crider, a professor at the University of Washington, and Max Needle, a video-game-style environment, already familiar to students, proved a great interface for simulating outdoor trips after the outbreak of Covid-19.

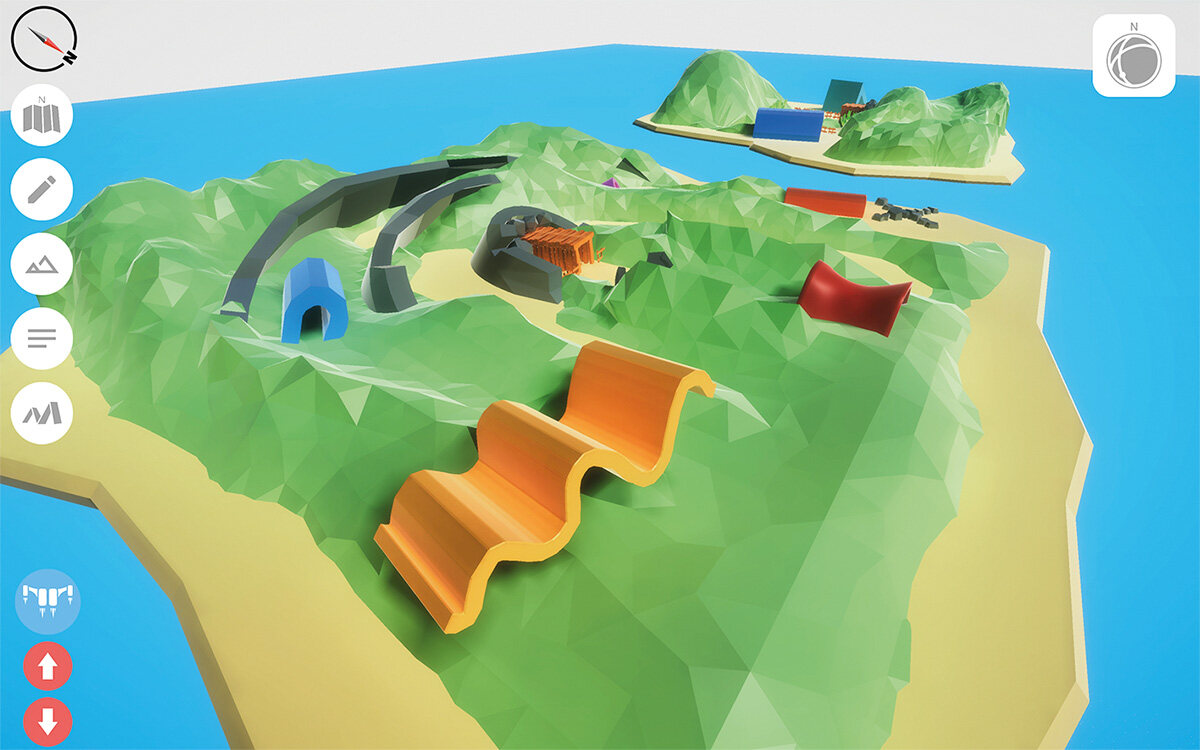

Alongside a team of designers, they developed virtual field visits to the Whaleback Anticline, a geology field site in Pennsylvania, USA, and a fictional site called Fold Islands. The experiences are designed to be open ended, allowing users to explore the sites and collect their own data using tools that simulate those that a geologist would have with them in the field. ‘So it’s a little different from a standard video game,’ explains Crider. ‘Here, you are making the decisions that a scientist needs to make in the field, such as where to go and what to measure.’

Crider had already begun working on computer-based field experiences, but the pandemic ‘put the project into high gear’. It has also shown that the kinds of changes needed to make GEES more accessible are possible, particularly for disabled students who face barriers to inclusion. According to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, roughly 17 per cent of UK geography undergraduates have a known disability.

The barriers to fieldwork go beyond the obvious physical ones, and for many academic staff, too, fieldwork can be a challenge. A 2018 survey of GEES academics who identified as having a mental health condition revealed that many found the stress of managing field trips an ‘ordeal’. Other issues include the financial burden of field trips, childcare responsibilities, reports of harassment and discrimination in the field, and problematic destinations (in 2020, Imperial College London cancelled its annual field trip to Oman, citing risks to the safety of LGBTQ+ students and staff).

Clare Bond, an earth scientist and professor at the University of Aberdeen, says that virtual field trips also provide valuable complementary learning experiences for students without accessibility issues, and can be used to expose students to a wider diversity of field areas. In an analysis of learning outcomes from a virtual field trip, she notes a much higher standard of data synthesis and analysis. ‘Often, students’ capacity for learning in-field isn’t actually that high because they’re busy dealing with the logistics – the rain, long walks.’

Virtual experiences give students and researchers a ‘dry run,’ agrees Crider. ‘There’s no real substitute for being out there in the natural environment and seeing things at the scale and in the complexity that the real world has to offer,’ she says. ‘We’ll never stop needing to go outside, but there may be situations where the digital terrains are just as useful, or enable more people to experience and make observations.’

Crider believes that virtual field trips could become part of a ‘new normal’ for research and education. At Aberdeen, elements of virtual learning have been integrated into most of the courses as part of the university’s broader vision of accessibility, rather than being used as ad-hoc solutions for individual students. ‘We’ve always put options in place, but they were specially designed for specific people and left them with little choice. Now it’s down to the student to lead, to tell us what they want to do and how, so that they can create something that’s best suited for their life and ability.