Immunisation has saved millions of lives, but new vaccines are urgently needed. Now we know where to focus our efforts first

By

Every 43 seconds, a child dies from pneumonia. Of all the infectious diseases, including diarrhoeal diseases and malaria, it’s the single largest driver of child mortality.

Pneumonia has no single cause; it can develop from airborne pathogens – bacteria, viruses and fungi – but the most common cause is a bacterium called Streptococcus pneumoniae. Over the last few years, however, reports from low-income countries have shown that a significant number of children are dying from infections caused by another pathogen, one that has developed resistance to last-resort antibiotics.

Our related medical reads…

Anecdotally, health experts were aware that Klebsiella pneumoniae, a bacterium commonly found in the intestine, was a growing problem in many hospitals. Babies were developing infections within hours of being born, often leading to death in weeks.

‘We’re increasingly seeing that K. pneumoniae is highly resistant to the majority of existing antibiotics, and that, of course, translates to more children dying,’ says Mateusz Hasso-Agopsowicz, an immunologist and expert in vaccine development at the World Health Organization (WHO). ‘In low-income countries, it’s responsible for 40 per cent of neonatal sepsis cases, which translates to around 80,000 deaths per year.’

Only recently have scientists had the data to confirm the substantial impact of K. pneumoniae on child mortality, which Hasso-Agopsowicz believes to be the reason why the pathogen has been largely overlooked by vaccine researchers – until now.

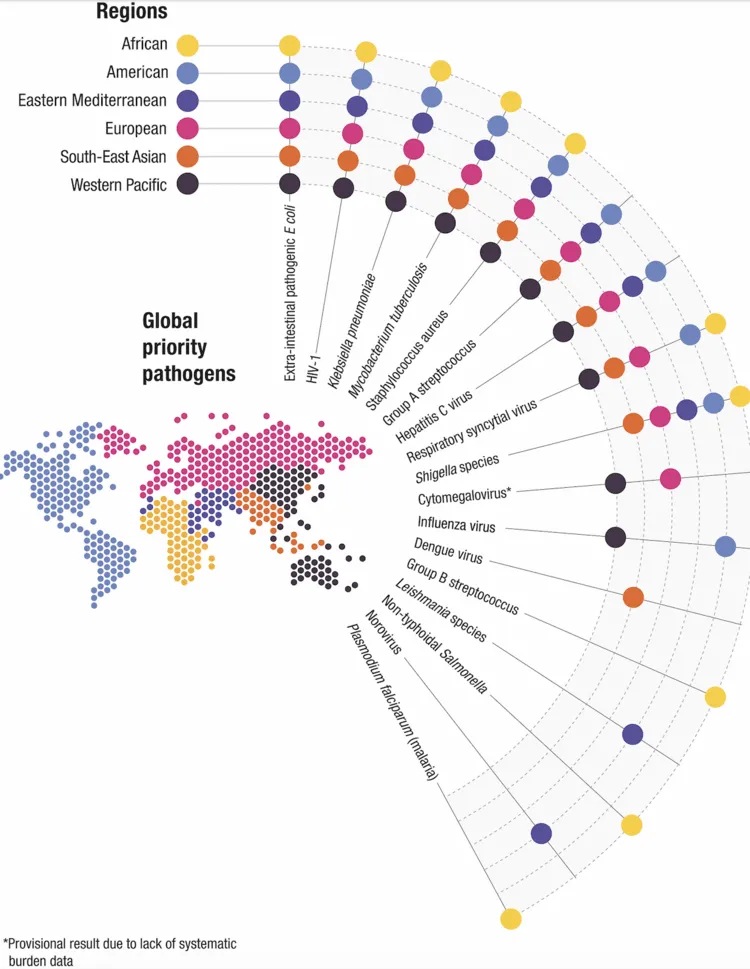

In a newly published report, the WHO has identified 17 pathogens, including K. pneumoniae, as top priorities for new vaccine development. While the study reconfirms long-standing priorities – such as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis, three diseases that collectively take nearly 2.5 million lives each year – the list also includes the group of parasites that cause Leishmaniasis, one of several neglected tropical diseases.

Hasso-Agopsowicz, who led the study, explains that pharmaceutical companies looking to develop new vaccines have historically lacked the scientific guidance needed to focus their work where it’s needed most.

‘Too often, global decisions on new vaccines have been solely driven by return on investment, rather than by the number of lives that could be saved in the most vulnerable communities,’ agrees Kate O’Brien, director of the immunisation, vaccines and biologicals department at the WHO.

Critically, Hasso-Agopsowicz and his colleagues reached out for input from regional health experts, resulting in the first global effort to prioritise pathogen research (based on criteria that included regional disease burden, antimicrobial resistance risk and socioeconomic impact). The approach is ‘a departure from the conventional “top–down” prioritisation largely driven by the interests of people from high-income countries,’ says Peter Figueroa, chair of the Caribbean Immunization Technical Advisory Group, who was involved in the study.

Worldwide, vaccines have made an unparalleled contribution to global health. Their greatest achievement has been the eradication of smallpox, a disease that killed more than 300 million people in the 20th century, which no longer exists outside the confines of a few secure laboratories.

A recent study published in The Lancet reveals that over the past 50 years, global immunisation efforts have saved an estimated 154 million lives, the vast majority of which – 101 million – were infants. While anti-vaccination movements have gained traction in recent years, studies continue to show that the vast majority of people around the world still trust vaccines.

However, as climate change, conflict and antimicrobial resistance increase the spread of infectious diseases, urgent investment in new vaccines has become essential.

In 2024, South America suffered the worst outbreak of dengue fever on record, with more than 3.5 million cases in the first three months of the year, compared with 4.5 million in all of 2023. Experts warn that as the climate becomes warmer and wetter, the type of habitat favoured by the mosquitoes that spread the disease is likely to expand. The good news is that a recent clinical trial of a new dengue vaccine has shown promising results, but there’s a long road ahead.

While the first vaccine for malaria received major regulatory approval in 2015, it didn’t become part of vaccination programmes in Africa until 2024. In that time, 143,000 children’s lives were lost to the disease.