Photojournalist Nick Danziger travels to Burkina Faso to document the devastating impact of sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease is the world’s most common genetic disorder. It affects about 50 million people, with an estimated 300,000 babies born every year with the disease; the majority of those affected live in or come from sub-Saharan Africa or are Hispanic people from the Caribbean. The sickle cell gene has also been found in people who live in, or whose families are from, the Middle East, India, Latin America and Middle Eastern Mediterranean countries. It has also been found in tribal populations in India and among American Indians. Despite the disease affecting so many, most of those who’ve heard of the disease, including some medical practitioners, are unaware of its many symptoms or the disabilities that it causes.

People who suffer from sickle cell disease produce an abnormal form of haemoglobin that causes their red blood cells to become rigid and form an aberrant crescent shape. The cells have a shorter lifespan and can block small blood vessels. It’s possible to forewarn parents of the risk of passing on the gene. However, millions of people remain unaware that they have the disease, mainly because there isn’t a willingness to invest in public campaigns, medical practitioners receive limited training, and there’s a lack of testing.

As Béatrice Garrette, director of France’s Fondation Pierre Fabre, one of the few organisations investing in services to help those with sickle cell and providing testing, in particular, for newborn babies, says: ‘More, much more, can be done to not only provide awareness and understanding of which parents will transmit what type of damaged genes, but to explain the risks involved for their offspring.’

Theresa & Osman

Since childhood, Thérèse, now 34, has been racked by crippling joint pain – so bad at times that she got her parents to tie her down until it passed. She was diagnosed with sickle cell two years ago. As Thérèse rests with her husband, Osman, 35, and four-year-old daughter Fadila, she tells me: ‘It hurts when I walk, when I sit, when I bend over to wash the clothes; my hips ache permanently. I can’t do what I want to do; it’s depressing. My cartilage is being eaten away. It’s calcified, which they tell me will make the operation [for a hip replacement] even more complicated because I’ve left it too long.’

Her husband frets because he can’t afford the medicine required to treat his wife. ‘I just want my wife to be healthy,’ he says. ‘She isn’t and the stress has made me ill. When I come home I’m sometimes in tears. If she was healed, I would be too.’

In a dozen sub-Saharan African countries and Haiti, the Fondation Pierre Fabre is financing medical services for those affected by sickle cell and improving understanding of the disease among medical practitioners. However, it’s clear that for most of the world’s pharmaceutical companies, the level of research and investment into such a damaging and prevalent disease isn’t what it should be. You can only conclude that this is because it’s a disease that affects mainly Africans. Indeed, among those few organisations offering assistance, there’s frustration at the lack of funding to alleviate the suffering of those whose lives are blighted by sickle cell. Claude Fabbretti, head of Monaco’s Red Cross’s International Humanitarian Department, which provides free prostheses to sickle cell patients who need hip joint replacements, explains: ‘It’s an orphan disease.’

Today, there are an estimated 100,000 cases in the USA, predominantly in the South, and 10,000 cases in the UK. Increasingly across Europe and the USA, we will need to test for the mutated gene because of the complications that can result from a blood transfusion. This pressure will only increase as global migration patterns reinforce the steady spread of the disease.

One in three people in Burkina Faso carries the sickle cell gene. Like several West African nations, it’s blighted by low economic indicators and sits close to the bottom of the World Bank’s Human Development Index. The problems of Burkina Faso’s dysfunctional health service are compounded by the fact that between 40 per cent and 60 per cent of its 21.5 million citizens live outside the government’s control in areas where the jihadists’ writ is all but complete. The conflict has killed thousands of civilians and displaced millions, with tens of thousands flooding the capital, Ouagadougou. In areas outside the government’s control, schools have been forcibly closed. A long-standing drought and food shortages have led to further deterioration of living conditions for those who are unable to flee the fighting.

Scholastique

Scholastique’s family has been devastated by sickle cell. Both her brother, Odillon, and her father, Jean Baptiste (pictured at the top of the story), suffer from it, as does her younger sister, Aurélie. It killed her mother. Odillon works as a trainee mechanic and Scholastique, 17, is being trained as a tailor. They cycle to work along dirt tracks six days a week – Scholastique’s journey is eight kilometres each way and her brother’s six kilometres. Scholastique says: ‘It’s tiring in the hot weather. We’ve been told not to do so much exercise because it will affect us, but we have no choice – it’s too far to walk to work. My day is very full as I also do the cooking and wash the clothes for the family.’

Millions of Burkinabé citizens have never had the cheap, efficient blood test, which provides a result within ten minutes, because the US$4 fee is beyond their means. As a result, thousands of infants born with sickle cell anaemia face premature death; in Burkina Faso, two per cent of children under the age of five born with the disease will die. Youngsters face delayed growth and puberty; possibly hundreds of thousands are living with gallstones, bouts of chronic pain, higher risk of infections, swelling of hands and feet, breathlessness, reduced vision, and severe pain in their bones and joints, which often leads to them developing a limp and even necrosis. Most don’t know the cause of their conditions. They’re also at risk of a stroke if the blood vessels to the brain are blocked, splenic sequestration (when too many blood cells get stuck in the spleen) and acute chest syndrome, which can cause lasting and permanent lung disease. These are just some of the symptoms facing those with the disease. There are others: priapism in men, and pregnant women face pre-term births and babies with low birth weight.

Until recently, the only cure for sickle cell disease was a bone marrow transplant. However, in December 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration approved two new genetic therapies to treat the disease, but they’re unavailable in the most affected countries, and even if they were available, they would be unaffordable for almost everyone.

These are the harrowing stories of individuals and their families living with the disease, and of those who are dedicated to treating them.

Dr Dieudonné Oedraogo

Gynaecologist obstetrician Dr Dieudonné Ouedraogo regularly treats pregnant women with sickle cell at Schiphra Hospital in Ouagadougou, often giving them morphine in the final stages to cope with the pain.

He says: ‘The risks during pregnancy are greater for mothers with sickle cell. It adversely affects pregnancy and can lead to an increased incidence of maternal and perinatal complications such as pre-eclampsia and pre-term labour. The baby doesn’t grow as expected in the womb and there can

be foetal death in the womb, hence we need to provide ultrasounds during each trimester.’

Claudine Farama & Moussa

Moussa, 26, has just fallen asleep at the desk of Saint Camille Hospital’s social services officer Claudine Farama. He was given an analgesic injection after arriving at the hospital in Ouagadougou in extreme pain – he didn’t have the US$4 to pay for it, but Claudine paid for it from her emergency fund. Moussa is training to be a nurse but is struggling to keep up and desperately needs hip replacement surgery. His parents have saved the US$400 needed for the operation but haven’t been able to raise enough money for the post-operative care. Earlier, he told me: ‘My parents live in the village and produce barely enough sorghum to support themselves.’

As he sleeps, several mothers enter the room saying they need money for baby milk and medicine. Claudine opens her wallet and gives them some cash. She tells me: ‘When I no longer have donors’ funds to give them, my wallet empties.’

Kadi

Kadi, 19, says: ‘I was 14 when I first felt pain in my hips. I came to the hospital with my mother [Mamata, above]. They tested both of us, and they wanted to test my father, but he refused. I hobble more and more, but they tell me I’m too young to have a prosthesis, which makes me sad as I was teased at school. I have stood up to the bullies. Maman supports me a lot, but I haven’t told her about the teasing.

‘Papa is not kind to me. Since he was told I had sickle cell, he’s stopped talking to me. He says it’s maman’s fault. He wants us to move out of the house. Maman suffers; she only stays because of me. I want to leave our home, he’s so mean. He gave me a mobile phone but has taken it back; I don’t know why. He doesn’t talk to me even when we all eat together. I have three siblings, one of whom has also been hospitalised. I have placed my faith in God and go to church three times a week to give me the courage to continue. I am studying to become a cashier. My classmates don’t know I have the disease.’

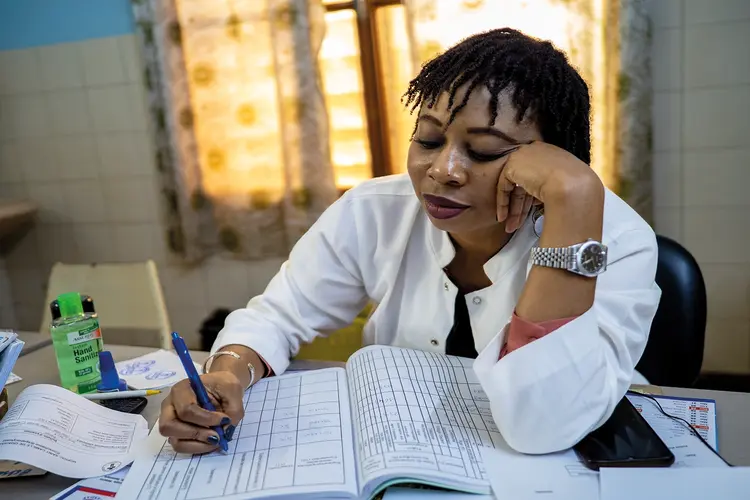

Dr Catherine Coulibaly

Dr Catherine Coulibaly, is a specialist in sickle cell at Saint Camille Hospital in Ouagadougou. She says: ‘I see 15 to 20 patients a day, but I have 3,000 regular patients from three months old to 82 years of age. If I didn’t cap the number of patients, I would probably have 4,000 to 5,000 patients.

‘I have seen the fear the patients have, often of early death, which doesn’t need to be the case, and the stigmatisation – even people in the health sector are afraid of sickle cell patients; they worry the patient is going to die in their health centre.

‘Many patients feel haunted. I try to explain and reassure them, particularly now that we know so much more about the disease and how to treat it. The issue is that many sufferers don’t come to us; they don’t know how to find us, and then when they do, they need regular check-ups, and many have great difficulty in paying for the treatment.

‘It’s tough; I just received Shabib, a nine-year-old [her first patient of the day] who’s in great pain; he’s a new patient and it’s sometimes difficult not to cry. Life expectancy for people with sickle cell disease has more than doubled since the 1980s. Nonetheless, if you have sickle cell, you need to avoid very strenuous exercise and other activities that can lead to you being out of breath. Alcohol and smoking should also be avoided because with alcohol, you can become dehydrated, and smoking can cause serious lung conditions. You need to avoid altitudes above 1,500 metres because of hypoxaemia. Even exposure to cold air, wind and water may cause a painful event by triggering red blood cell sickling in exposed areas of the body. Those with the sickle cell disease are prone to frequent infections, leg ulcers or severe sores, bone damage, gallstones, kidney damage, eye damage and potentially multiple organ failure.’

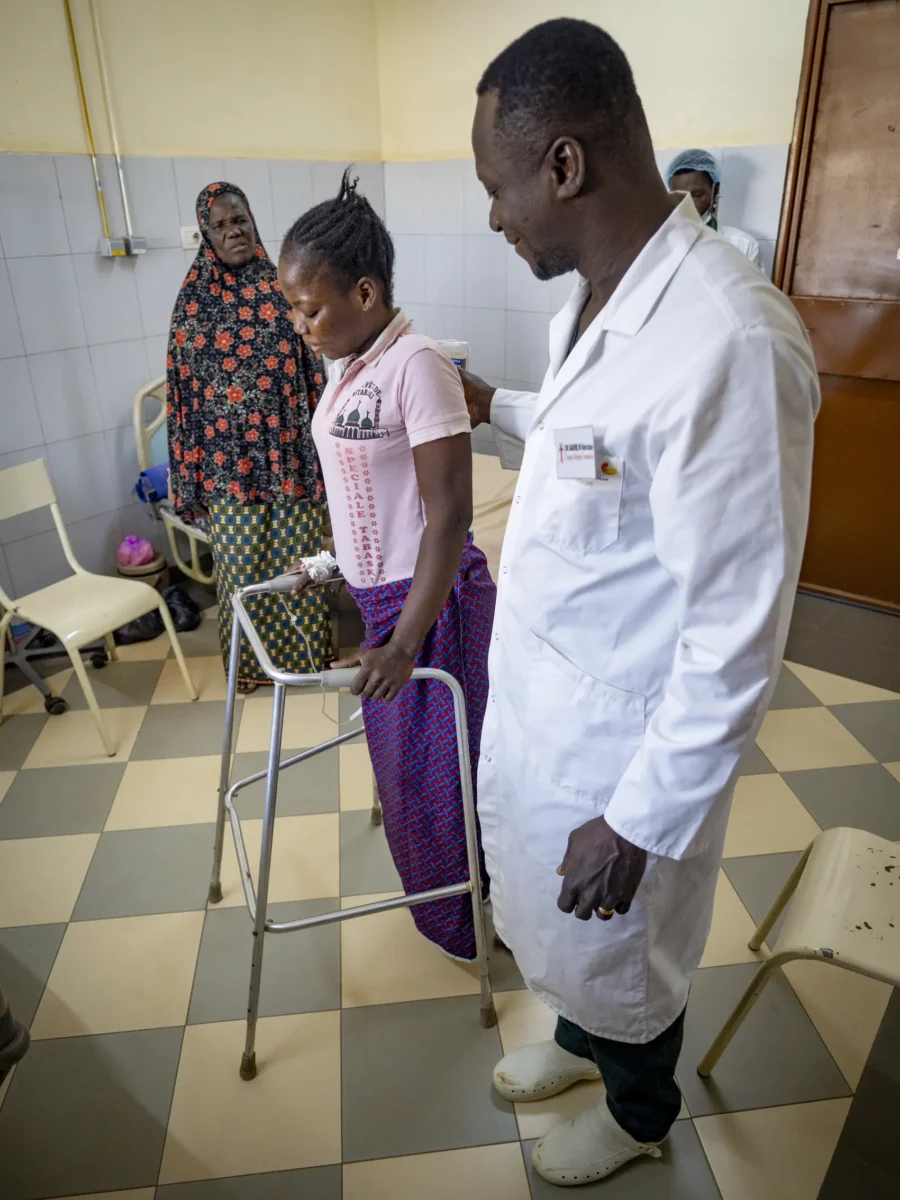

Safiata & Dr Narcisse Dabiré

Safiata, 27, has just had a hip replacement at Saint Camille Hospital, Ouagadougou. She says: ‘I worked in the fields with my family. The aches and pains began when I was seven years old, like being jabbed by sharp quills. I couldn’t sleep; we didn’t know what it was. My father suffered too. He stopped driving because his vision became blurred. My mother never suffered. It wasn’t until my father was 41 years old that he was diagnosed with sickle cell. For years, the pain persisted, then it changed. For the last four years, my hips started to ache so much every day, I began to hobble. My husband didn’t want to know. He gave me traditional medicine; he believes it’s a curse. It was my brother who brought me to see a doctor and thanks to him I will have a hip joint replacement. My husband threatened me, saying if I left to go to the city to be treated our marriage was over. He refuses to help. My brother is a school teacher and the only breadwinner in the family. He’s borrowed money for the operation.’

The operation was carried out by Dr Narcisse Dabiré (above), an orthopaedic surgeon. He tells me: ‘I love what I do. It’s a contagious feeling of happiness for both the patient and myself when the operation is a success. The operation can take up to three hours. The patient is under a local anaesthetic and is awake during the operation.

‘Of course, the costs are not the only barrier to receiving a prosthesis. We need specific sizes that aren’t normally catered for because our physiognomies in Africa are different, and there’s more money to be made in Europe and the Americas. There’s also a shortage of blood and because of the war, there’s a priority for getting the blood to the military rather than the civilian population.’

If you have any questions about Nick and his work, check out our Reddit ‘Ask Me Anything’ thread here, where Nick answers many of your queries on photojournalism, the ethics of the industry and more.