The medieval Gough map reveals evidence of a legendary Welsh kingdom claimed by the sea

By

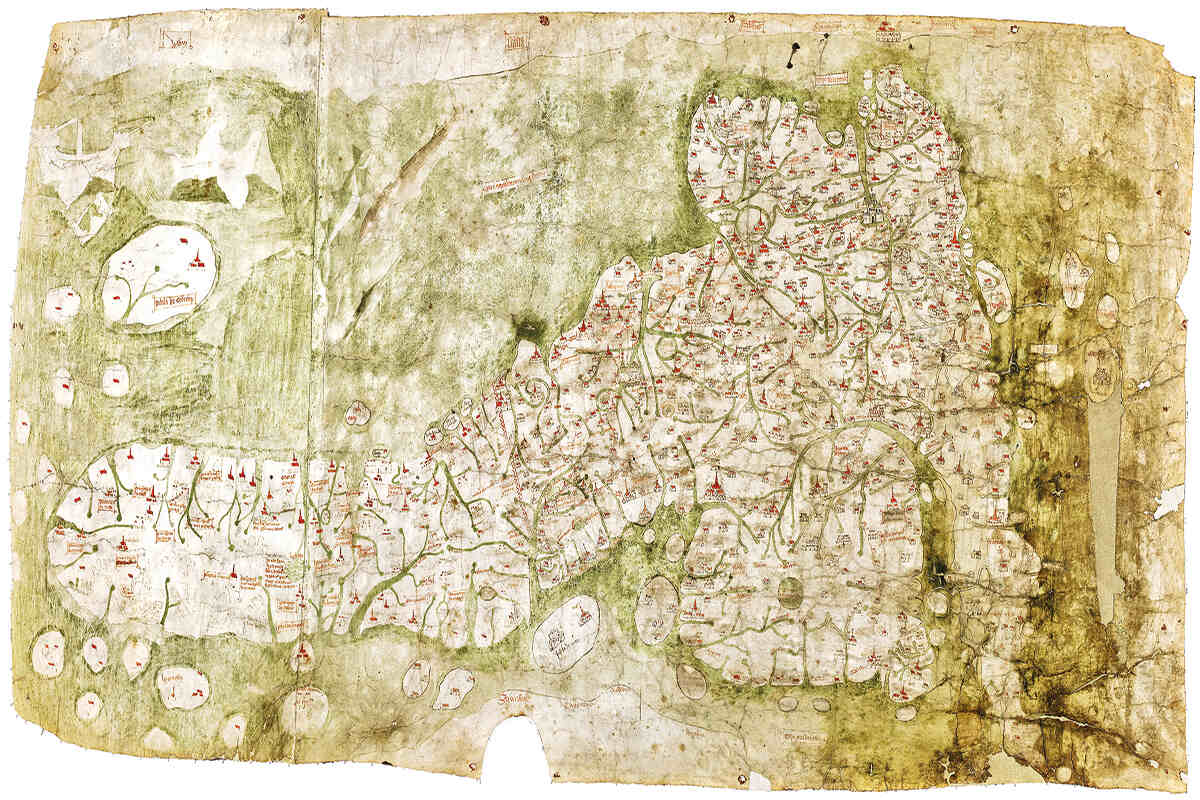

The medieval Gough Map, held in the collections of Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, is the earliest surviving map to show an identifiable coastline of the British Isles. But one area depicted in Cardigan Bay in Wales doesn’t match any land recognisable today.

‘I noticed there were two quite prominent islands on the map that clearly don’t exist anymore,’ says Simon Haslett, professor of physical geography at Swansea University. Curious about what the islands could represent, Haslett and David Willis, professor of Celtic at Oxford University, analysed all of the sources available to them – including local legends of a land lost to the sea.

Several different stories in Welsh folklore tell how an area of land to the west of Wales disappeared beneath the waves of Cardigan Bay – the earliest known version appears in the Black Book of Carmarthen, a 13th-century Welsh manuscript. In a later version, a land called Cantre’r Gwaelod (the ‘Lowland Hundred’) is flooded by the drunken gatekeeper Seithiennin. Haslett explains that while drawing upon all the different strands of evidence, ‘we couldn’t overlook the folklore and the Celtic literature that offer geo-mythological support for those islands having existed.’ Together, this ancient map and the legends and folklore of a lost Welsh kingdom hint at how the Welsh coast has evolved since the end of the last ice age, roughly 10,000 years ago.

Studying how ancient oral and written traditions account for geological phenomena – floods, earthquakes, fossil discoveries – can provide valuable information about past events, or how a landscape may have changed over time. Flood myths can be found in most ancient cultures and Cantre’r Gwaelod is often described as a ‘Welsh Atlantis’, but Haslett is keen to emphasise that the island in Cardigan Bay didn’t actually sink. ‘There are no sunken islands,’ he says. ‘People like to think about submergence, but that’s not what we’re suggesting happened.’

Instead, Haslett and Willis propose that the islands were remnants of a landscape underlain by soft glacial sediment deposited during the last ice age. Over time, this land has been eroded by the sea, rivers and surface runoff from the land, carving it into islands before these, too, were worn away, disappearing by the 16th century. Submarine formations of boulders and pebbles, known locally as sarns, mark the location of the islands, left behind after the finer sediment had eroded.

‘Evidence from the Roman cartographer Ptolemy suggests that the west Welsh coastline 2,000 years ago may have been some 13 kilometres further out to sea than it is today,’ says Haslett, meaning between five and ten metres of land was eroded per year between Ptolemy’s records and the drafting of the Gough Map. Such rates of erosion are high, but not atypical.

There are other places in the same period that suffered similar erosion rates. Dunwich, in the east of England, was probably lost to the sea in a similar way,’ says Haslett.

Understanding the processes along the Cardigan Bay coast could help us figure out how it will continue to evolve in the future, essential in an area at risk from sea-level rise. Erosion is still occurring in these areas, albeit at a slower rate. Haslett says that remnants of the soft glacial sediments still remain, sheltered by hard rock that protects it in landforms such as groynes, and by the artificial sea defences erected to protect the vulnerable communities on the coast of Cardigan Bay.