The Northern Lights are an awe-inspiring phenomenon: what causes them, and where can you see them

Words by Sophie Cohen

What causes the Northern Lights?

The scientific name, ‘aurora borealis’ was coined by Galileo Galilei in 1619, who believed that the lights were reflections of sunlight in the atmosphere. In Ancient Greece and Rome, the lights were believed to be representative of the Goddess of Dawn (Aurora in Latin), who would produce colours across the sky by riding her chariot to tell her sisters the sun and the moon (Helios and Selene in Greek) that a new day had started.

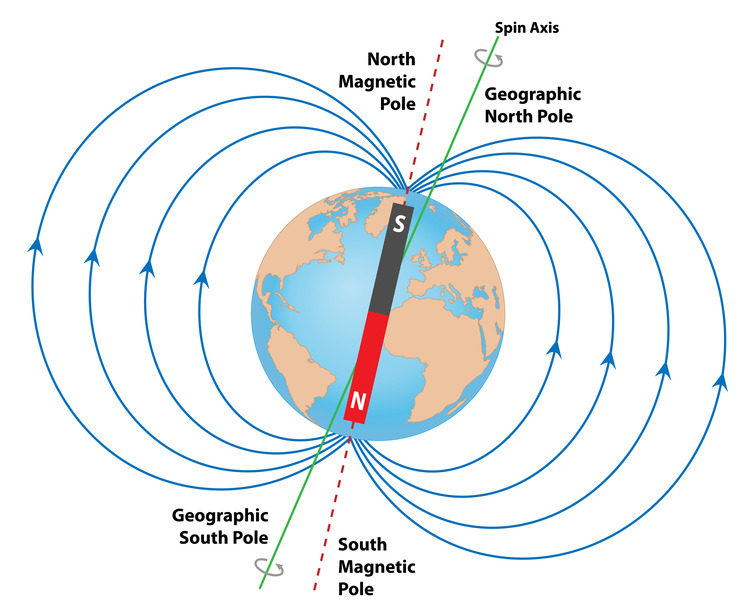

This colourful phenomenon is actually the product of solar activity from the sun, 15 million kilometres away. The display starts at the Sun’s most outer atmosphere, known as the Corona, which emits charged particles known as ions, in all directions. This flow of particles from the sun is known as the solar wind. When these solar winds head towards Earth, they are met by the Earth’s magnetic field, which acts as a barrier protecting us from any potentially harmful particles.

Why can you sometimes see the Northern Lights from non-polar regions?

The Earth’s magnetic field is oval-shaped and strongest in the North and South Polar regions. Therefore, some of the solar wind ions get pulled in and react with the Earth’s atmosphere. When these charged ions at the poles react with the oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the atmosphere, they produce a huge amount of energy, resulting in the sky’s colours.

Why are there different coloured lights?

The solar wind ions react with either oxygen or nitrogen, producing a different colour. Oxygen reactions create the most commonly observed green colour and nitrogen, a pink-red colour. The altitude at which the solar wind ions and earth’s particles have collided produces different colours. The green colour indicates the reaction has occurred between 60-150 miles above the Earth’s surface, while blue becomes visible when nitrogen atoms collide with solar wind ions at less than 60 miles above the Earth’s surface. Rare red tints are seen when oxygen and ions react at high altitudes more than 150 miles above the Earth’s surface.

The sun occasionally emits a larger volume of ions than usual in what is known as a coronal mass ejection. This increases the stream of ions from the sun colliding with the earth’s atmosphere at lower latitudes, making them visible in parts of Europe, North America, and East and Central Asia.

When and where can I see the Northern Lights?

While predicting the exact timing and location of the Northern lights can be challenging, they are known to be most visible in the regions of Northern Scandinavia (Sweden, Finland, Norway), Canada, Iceland and Alaska. September to March, with the longest periods of dark night skies give the clearest views of the phenomena.

The Northern Lights from space

While the majority of us will only ever see the Northern Lights from below, astronauts at the International NASA Space Station have been lucky enough to get a glimpse from above. The photo above shows a snapshot of the Northern Lights over Earth from Space

The rise of Northern Lights tourism

The Northern Lights have become a hotspot for tourism. Following the release of Joanna Lumley’s Northern Lights BBC documentary in 2008, international tourism from Britain greatly increased. Flights from central points in Europe to Tromsø (one of the best cities in Norway to see the Northern lights) increased. Northern Light holiday options range from package holidays in luxury hotels to cosy igloo stays and cruises into northern waters.

Your eyes deceive you

The significant rise in tourism of the Northern Lights has prompted photographers and visitors alike to notice an explainable but intriguing discovery: the lights as we see them with our bare eyes are not what they actually look like in reality. One such professional photographer who picked up on this was Mike Taylor, who stated that his high-quality camera would always capture far more of the lights’ colours, compared to the naked eye. This is due to the ability of our eyes to detect light in the dark. The rod cells in the eye which we use at night are only able to see light in grey, black and white undertones, meaning the appearance of the Northern Lights through our bare eyes can often appear much dimmer and fainter than on our cameras.