What is stratospheric aerosol injection, and is it safe to use as a way of mitigating the Earth’s rising temperatures?

By

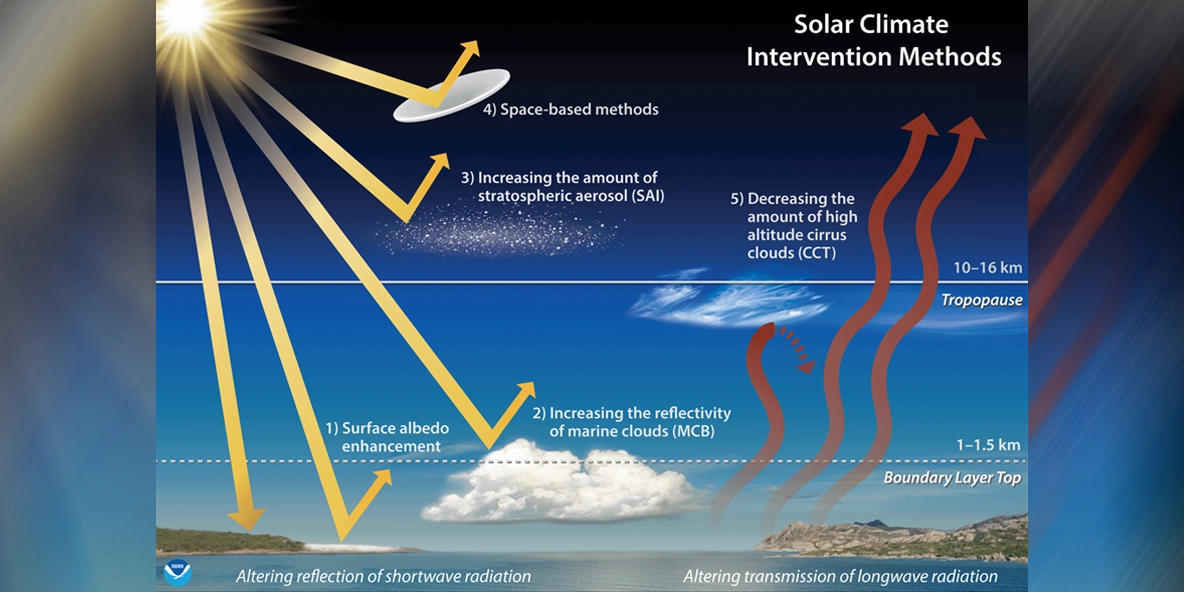

An aerosol sprayed into the atmosphere to help combat global warming. It sounds like something from a sci-fi movie, but this aerosol – otherwise known as stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) – is one of the most widely-researched solar geoengineering methods hoped to reduce the planet’s warming to below 1.5 °C in the battle against rising temperatures.

How does it work?

Stratospheric aerosol injection is a proposed type of geoengineering that involves injecting sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere. In turn, this produce sulphate aerosols that reflect the sun. The process aims to replicate the cooling effects that occur following large volcanic eruptions, which release sulphur into the stratosphere. However, stratospheric aerosol injection and volcanic eruptions are not identical models for one another: differences in aerosol size and the time and distribution of aerosols varies between both.

Aerosols placed in the stratosphere are able to produce a cooling effect 100 times larger than if emitted at a surface-level, although are far more difficult. Proposals to use SAIs involve using them on a global scale for multiple decades – so research will need to be conducted thoroughly before such geoengineering can be deployed.

While technology is still being developed to inject these aerosols into the stratosphere, scientists believe it is feasible that tethered balloons or a fleet of several hundred high-altitude airplanes may be used, which could take one or two decades to construct. To deploy stratospheric aerosol injections into the stratosphere, airplanes would need to reach at least 20 kilometres above ground – almost double the height that large military aircraft and commercial jets are able to cruise with current technology. Very small spy planes can operate at this altitude, but do not have the loading capacity to carry the large quantities of aerosol needed, estimated at several million metric tonnes per year.

The benefits of stratospheric aerosol injection

The most compelling reason to use stratospheric aerosol injection is its ability to cool down the planet. Current projections suggest that it is likely the 1.5 °C threshold set by the Paris Agreement will be exceeded by 2040 or earlier. Relying solely on reducing carbon emissions alone may be insufficient to combat climate change.

The cost of SAI is also estimated to be significantly lower than other proposed methods of limiting warming to less than 1.5 °C – with injections costing approximately several billion USD per year compared to the current global mitigation costs estimated at around several trillion USD per year for the electricity sector alone.

Risking the environment

Artificially controlling the Earth’s climate brings about many questions of ethics and morality. There could be unintended consequences to using stratospheric atmospheric injection too, including ecological impacts such as ocean acidification that has a negative effect on ocean life. Adverse health impacts to humans and animals may also occur through inhalation of aerosols, as the toxicity of such particles has not been studied in depth.

If SAI became a widespread and global measure taken to combat rising temperatures on Earth, it may also reduce the moral desire of fossil fuel companies to continue other ways of mitigating increasing temperatures and lower greenhouse gas emissions. It is important, therefore, that policymakers and researchers consider how SAI and other methods of lowering temperatures can work hand in hand.

Such solar geoengineering technologies could also be weaponised for terrorism use, or used by developed countries solely, exposing poorer countries to even greater environmental risks. Less quantifiable risks – such as threat of conflict between countries over appropriate usage – are also factors that need to be considered as well as more determinable risks in order to clearly understand the full consequences of implementing SAI.

What is the future of stratospheric aerosol injection?

According to analysis from MIT, it is feasible that one or more countries could begin to deploy solar geoengineering in just five years. However, such research would be unjustified on such a large-scale due to the potential consequences it could have on the stratosphere’s composition. Deploying SAI both rapidly and on a mass scale could cause even more unforeseen effects on the planet – so it is in countries’ best interests to roll out solar geoengineering techniques such as SAI in a gradual way, reaping greater environmental and political benefits and maintaining relations between countries and policymakers as they do so.

Some researchers believe using SAI on a small scale at high altitudes in the lower stratosphere at 35° north and south – where the top of the troposphere is found at just 12 kilometres – could be a way of beginning to trial SAI in a safe and measured way. While commercial aircraft still cannot operate at that altitude, certain business jets, including Gulfstream, Bombardier and Dassault, can. Countries found at 35° north and south include a vast range of developing and developed countries from the United States, Australia and Japan to Pakistan, India and Argentina, ensuring fair representation from all parts of the world.

Although current models suggest that minimal effects will arise from using SAI, there are still unknown consequences and uncertainties that may occur by rolling out its usage. By continuing to investigate its effects thoroughly and through moral, ethical and environmental lenses, its use can be ensured as sustainable and safe for today and future generations to come.