Photographer Laurent Weyl travels to French Polynesia to meet the children leading a new approach in marine conservation

It’s difficult to imagine a more remote place than the Marquesas Islands, a group of volcanic islands that form part of the French Polynesian archipelago situated halfway between South America and Australia in the Pacific Ocean. Yet even here, or perhaps because of the islands’ very isolation, people have an acute awareness of the dangers that humans pose to the natural world.

During a 2013 survey of the islands, carried out by a scientific team sponsored by UNESCO, a group of local children were asked whether they could come up with some ideas as to how to protect their native maritime environment. They responded with an ambitious plan, suggesting that they be allowed to manage their own piece of ocean.

Despite the young age of its proponents, the idea quickly took off. Committees were formed, objectives identified and responsibilities distributed. The result was the creation of an Educational Managed Marine Area (EMMA). Its purpose was not only to protect this small patch of ocean from pollution and degradation, but also to welcome teachers, researchers and traditional users of the sea, such as fishers, to share their experiences and enrich each other’s knowledge of this invaluable resource.

The demands of the so-called ‘Children’s Parliament of the Sea’ that developed on Tahuata, the smallest of the inhabited Marquesas Islands, were simple but vital. Visitors to the area were asked to anchor boats in sand only, to not drain fuel tanks into the lagoon, to avoid touching flora and fauna, and to dispose of both artificial and human waste responsibly. Before long, the concept spread to the Marquesas’ four other inhabited islands, other parts of French Polynesia and, ultimately, to the French mainland, reaching some tens of thousands of pupils within just a few years. French Polynesia and the founding partners structured the concept to create an ‘EMMA’ label for schools that adhere to the requirements of the programme.

During Cop21 in Paris, a partnership was signed between the French minister for the environment, energy and the sea, Ségolène Royal, and Édouard Fritch, president of French Polynesia, to celebrate the Polynesian network of EMMAs and to begin to promote the approach across France. At the start of the 2016–17 school year, new schools began to create their own EMMAs in other parts of French Polynesia. At the same time, a national pilot programme was launched to establish eight new EMMAs in mainland France and French overseas territories.

French Polynesia is an overseas collectivity of France that consists of five archipelagos in the south-central Pacific Ocean: the Society Islands, Tuamotu Archipelago, Gambier Islands, Marquesas Islands and Tubuai Islands. Made up of 118 islands in total, it extends over more than five million square kilometres. The capital, Papeete, is on Tahiti, French Polynesia’s largest island.

French Polynesia

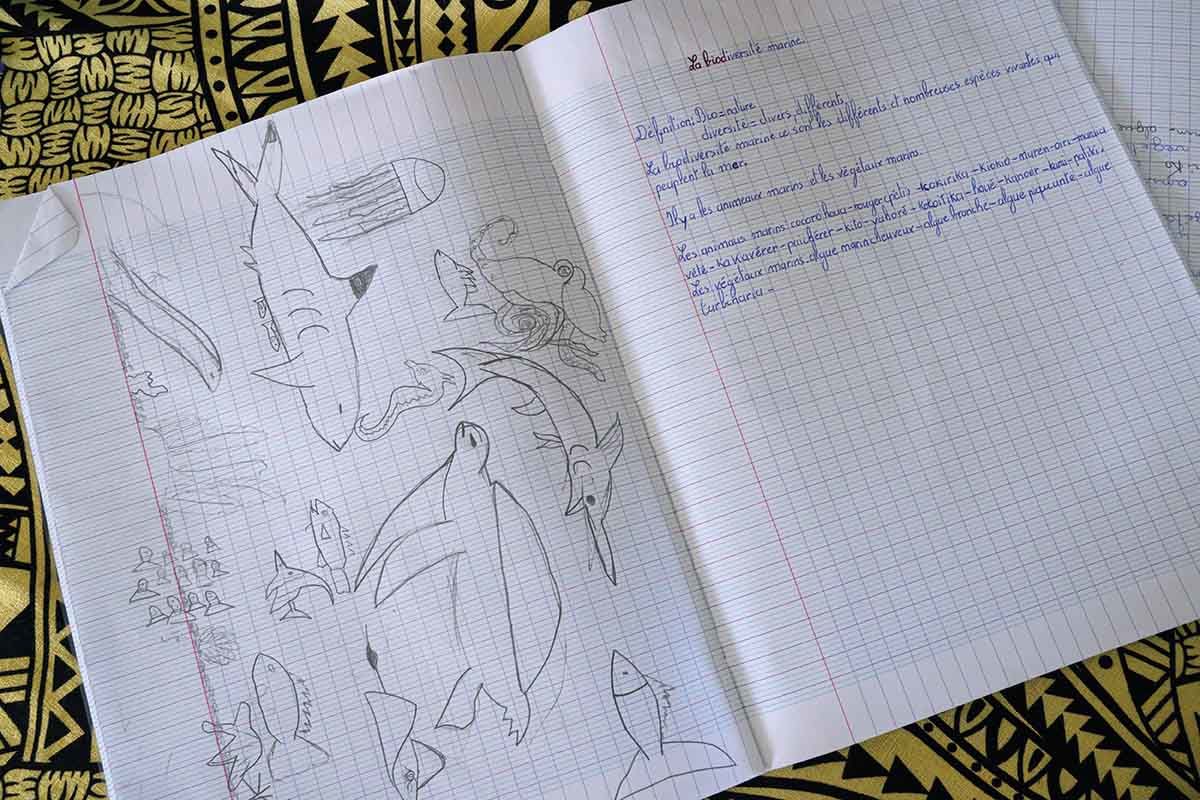

The islands and surrounding waters represent a biodiversity hotspot, comprising 20 per cent of the world’s atolls (a ring-shaped coral reef, island or series of islets) and 15,050 square kilometres of coral reef ecosystem. They are home to more than 20 species of shark. The waters around the Marquesas Islands support more than 550 fish species, including 26 species of shark and ray, and serve as a major spawning area for the bigeye tuna, which is listed as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List.

Today, the seas surrounding these Pacific islands face a range of threats, from habitat destruction, overfishing and coral bleaching to ocean acidification, marine pollution and the impacts of coastal development. Throughout their history, French Polynesians have practiced rāhui, a tradition of periodically restricting fishing and other activity in an area to allow the life there to recover. However, the development of intensive fishing throughout the Pacific is threatening the ocean-based Polynesian way of life. A 2019 survey found that nearly 80 per cent of people in French Polynesia think that their waters are in poor health and insufficiently protected, while 75 per cent believe that the number of fish in their waters is decreasing.

According to the IUCN, the EMMA approach is based on voluntary involvement and participatory management by students across a small stretch of sea. ‘The schools are at the heart of the management and decision-making mechanisms, and coordinate the actions to protect the marine environment. The project also seeks to share scientific knowledge about the marine environment and to promote the proper use and culture of the sea with professionals.’

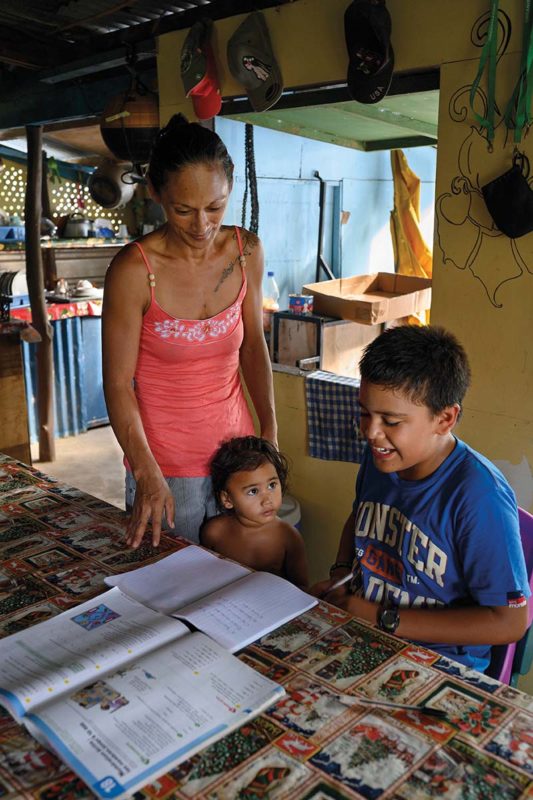

Each school is required to implement a programme of actions to prepare correct management of the area, including conducting an ecological survey in the chosen area involving the children, alongside scientific teams; establishing a children’s sea council to discuss the actions to be implemented; investing in educational activities within the areas so that the children can think for themselves by drawing on and developing new understanding in a real-life situation; and developing relationships with elected officials, professionals and academics in order to link up different generations. The overall goal is to build a global community network of young people who all engage in the management of marine protected areas, proving that even the most remote communities have the power to change the world.

Marine Protected Areas in French Polynesia

The Marquesas islanders, along with the inhabitants of other islands in French Polynesia, have long called for the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs) in their waters, citing a decrease in resources that forces local fishers to travel much further from the coast. There is no official definition of an MPA, but they all involve protective management of natural areas according to pre-defined management objectives.

In February 2022, a significant step forward was taken when the president of French Polynesia, Édouard Fritch, announced the creation of a network of MPAs with an area of more than one million square kilometres within the Polynesian exclusive economic zone. He described two reserves of 500,000 square kilometres each, the first (Rahui nui) located in the south-east, the second to be created before the end of the year. Together, they will form a network of MPAs reserved for artisanal fishing around each of the 118 Polynesian islands.

Although the announcement was welcomed in French Polynesia, mayors from the Austral and Marquesas islands continue to call for the creation of two large-scale, highly protected MPAs around their islands. ‘The council of Marquesas mayors and the Marquesan population have been working for nearly a decade to create a large marine protected area, called Te Tai Nui A Hau, or the Ocean of Peace,’ said Benoît Kautai, president of the council of Marquesas mayors in an interview with Pew. ‘The Te Tai Nui A Hau project foresees three zones: a zone reserved for artisanal fishing, a zone open to industrial fishing and a strong protection zone that would forbid fishing in order to preserve the reproduction of bigeye tuna. President Fritch made announcements at the One Ocean Summit about the areas that will be dedicated to artisanal fishing in all the archipelagos. We’re waiting to learn the specific measures for the Marquesas Islands. For now, only the southeast of Polynesia will be included in the strong marine protection zone. We could therefore continue our collaboration with the French Polynesian government in order to study the possibility of dedicating an area to the protection of bigeye tuna, which would be the same area as a strong protection area of the Marquesas.’

According to the IUCN, numerous scientific studies have shown that large, fully protected marine reserves boost ocean health. They offer wildlife refuges in which to feed and reproduce, free from the threat of fishing, seabed mining and other extractive activity; help conserve and enrich biodiversity; and safeguard traditional cultures closely linked to the sea. In French Polynesia specifically, the IUCN argues that MPAs would bolster artisanal fishing zones around the islands, benefiting communities who rely on fishing. Experts also say that protecting large areas helps marine ecosystems to build resilience to climate change.