Ninety years after depopulation, the Scottish islands of St Kilda continue to exert a huge pull for visitors – and are a barometer of the threats faced by the UK’s seabirds

By

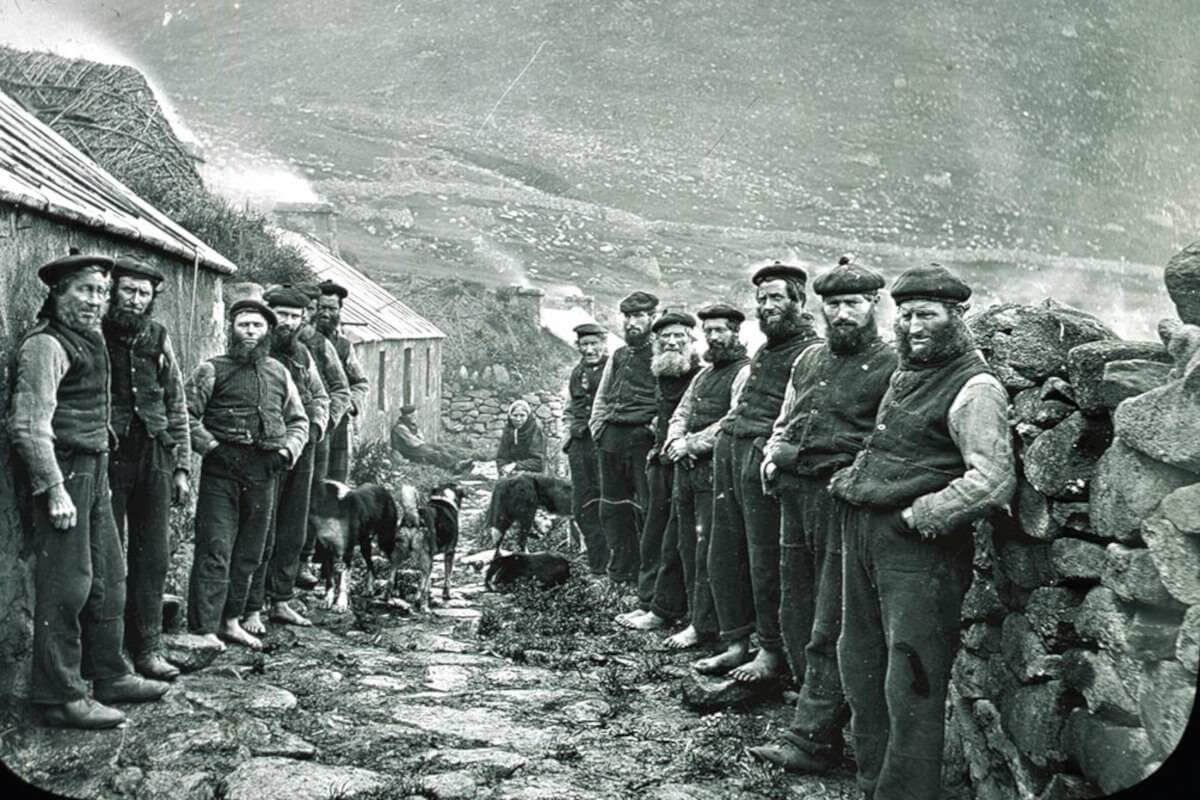

Thirty-six men, women and children were on board HMS Harebell as it manoeuvred out of the crescent-shaped harbour of Village Bay on the island of Hirta on the 29 August 1930. The ship was bound for Lochaline in Argyll and the passengers, the last residents of St Kilda, were leaving for good. Many could speak no English, only Gaelic, many had never been off the island. Before departure, the islanders had put on their best clothes, said prayers for the last time and left a bible and a small pile of oats in each of the 11 houses that had been occupied until that morning.

No doubt the events 90 years ago, when St Kilda joined the long list of depopulated Scottish islands, must have been unimaginably poignant and heart-breaking for those who left. For those older people who had no choice but to leave, it must have been unspeakably hard, though many accounts by those who were younger adults at the time speak of a sense of relief. Their departure was also hugely symbolic, for it marked the end of human occupation that had continued on the most isolated outpost of the British Isles, more or less unbroken for 2,000 years.

Today, St Kilda resonates with images of epic travel, of an exotic island hard to reach. For most visitors a journey to the island represents the fulfilment of a life-long dream. The archipelago comprises five islands plus attendant sea stacks. Formed of gabbro, granite and dolerite and shaped by ice, rain and waves, the St Kilda archipelago is unmatched anywhere in scale in the British Isles and includes the highest sea cliffs at 376 metres and the highest sea stack (191 metres). The chain is the remains of a large volcano active some 55 million years ago and the islands compete to outdo one another with their dramatic beauty: geometric sweeps akin to those of a South Pacific idyll pull the land up from sea level to high cliff ridges where they face the full rigours of the Atlantic Ocean.

Soay is the most westerly island, hidden for the most part behind the largest, Hirta, on which the islanders made their home on Main Street just above Village Bay. Hirta’s eastern ridges are all but conjoined with Dùn, while the stout lump of Levenish stands alone to the east. To the northeast lie Boreray and the two dramatic sea stacks of Stac Lee (meaning ‘beautiful stack’ in Gaelic) and Stac an Armin (‘stack of the warrior’).

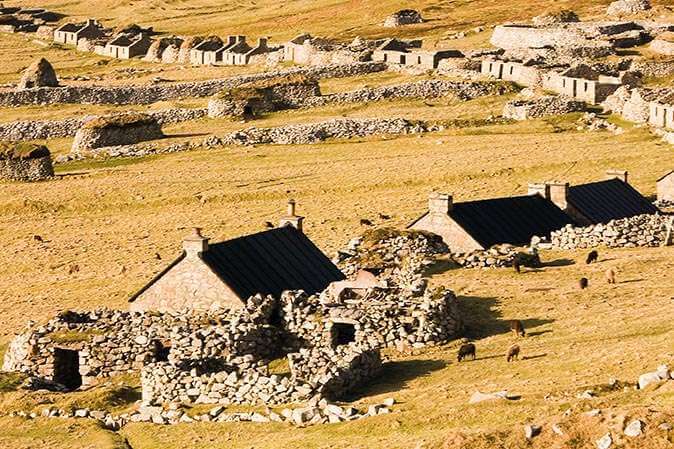

Though the islanders are long gone – the last surviving St Kildan, Rachel Johnson, died in 2016 at the age of 93; she had been eight years old when she left – the islands still bear the imprint of humans past and present. After making landfall on Hirta, most visitors explore the village, known as Main Street. House number three, once the home of William and Mary Ann MacDonald, who had 11 children, has been converted into a thoughtful museum with good accounts of the history of the island and its wildlife.

To the west of the village is the enclosed graveyard where most tombstones have weathered away. Up behind the graveyard lies a substantial pile of rubble known as Calum Mor’s house. More than 1,000 years old, this semi-subterranean house is a corbelled beehive shape of monumental proportions yet is said to have been built in a day by the eponymous Calum to prove his strength.

Main Street is constrained by drystone walls and restored enclosures. Behind the village, great sweeping contours rear up to The Gap, a steep hillside edge with no back to it – just a sheer drop to the sea. A large number of cleits (pronounced ‘cleets’) or storehouses run up towards The Gap in lines of striking symmetry. These squat igloo-like structures are all but embedded in the ground and were used to store eggs, fish and meat. Some are thought to date back more than 2,500 years.

Look across Hirta from the top of The Gap and the archaeological significance of St Kilda becomes apparent: you are gazing at a complete crofting landscape of the earlier 19th century. From the houses, fields, peat banks, tracks and enclosures, you can tell a comprehensive story about how the landscape was used.

The resources of the sea were just as important. The St Kildans were famed as nerveless cliff climbers, retrieving eggs and gannets from dizzying ledges. They ate the flesh and eggs of razorbills, fulmars, guillemots, gannets, puffins, great auks (before they were driven to extinction in the mid-19th century) and shearwaters. Eggs stored in peat ash could be preserved for eating in the winter months. At the start of the 20th century, the islanders were still taking 5,000 guillemot eggs every year.

This abundance of food explains why St Kilda, so often portrayed as ‘exotic’ or ‘remote’, was in fact a good place to live. The islands had a wide range of resources that made them attractive: fertile soil; abundant fishing and other marine resources; good grazing, and an unparalleled seabird resource which could produce meat, oils and feathers which at times were extremely valuable. ‘Although there were periods of famine and emergency, those happened everywhere, and there was no social safety net wherever you lived in Britain,’ says Kevin Grant, the island’s former archaeologist. ‘It’s contextual – would you rather live on St Kilda in 1880 or be a miner working six days a week, 14 hour shifts in a dangerous mine and living in a disease-ridden Glasgow slum, 12 to a room?’

Today, the attraction for visitors, apart from the stirring social history and landscapes, is the fauna and flora. The Soay sheep left behind by the islanders resemble goats rather than sheep and have more or less been left to their own devices. They are now the focus of a long-term study. Another curiosity is the St Kilda wren, Troglodytes troglodytes hirtensis, which has evolved into a much larger subspecies of the mainland wren. The St Kilda field mouse also grows to twice the size of its mainland cousin. Flora thrives doughtily in cliff-ledge communities, wet heath and grasslands. In all, 180 flowering plants and ferns have been identified on the islands. In 2012, a new species of dandelion, Araxacum pankhurstianum, was discovered.

Above all, though, St Kilda is a seabird city with 17 species regularly breeding on the archipelago. The headline act is the world’s second-largest gannet colony, home to 60,000 pairs of the birds, along with the UK’s largest fulmar colony (67,000 pairs) and its largest puffin colony (140,000 pairs). At dusk and dawn, storm petrels and Manx shearwaters can be seen in their hundreds. Exploring the archipelago’s coastline by boat, the air can appear full of soot and white confetti as birds in their thousands zip, flutter and scuttle back and forth.

Yet this magnificent spectacle masks some deeply disturbing underlying trends. The 2019 National Trust for Scotland (NTS) Seabird and Marine Ranger Annual Report revealed that many seabird species are in steep decline on the islands. For the second year running, not a single black-legged kittiwake nest was recorded on Hirta or Dùn, a catastrophic 100 per cent decline since a peak of 513 nests in 1994. Great skua nests have now declined by 22 per cent since 1997.

One long term factor driving the decline, suggests Grant, is the historical management of seas and land by generations of St Kildans. ‘Entire species of seabirds were hunted to extinction on the islands, and we have no idea how present-day seabird populations still feel the effects of periods of intense exploitation,’ he says.

However, Grant and others see climate change as a more formidable factor.

‘The sea temperature is increasing, which is changing plankton communities and that is having knock on effects through the whole ecosystem ending at seabirds,’ says Jeff Weddell, senior natural heritage advisor, NTS. ‘It’s pretty clear this is the case, there is growing scientific evidence. Most of these seabirds rely on sand eels as their main prey item, but they’re declining as the sea ecosystem changes due to warming.’ Overfishing of sand eels for animal feed and other products is also directly implicated.

Not all birds are struggling. A 2018 survey put the puffin colony on the north-eastern slope of Dùn at 34,753, statistically indistinguishable from the previous estimate in 1999. Evidence suggests that the density of burrows in the main colony has approximately doubled since the 1970s.

Scientists pay attention to what happens on St Kilda because it is viewed as a barometer for the wider natural environment. ‘St Kilda is the biggest seabird colony in the UK by far, twice as big as the next biggest,’ says Weddell. ‘It’s free of non-native predators such as rats, so St Kilda shows us how an unmodified, predator-free seabird island population is faring in the face of climate change and fishing.’

The NTS is attempting to aid seabird recovery through the Biosecurity for LIFE project, which aims to create habitats that provide safe places to breed. Yet this scheme is jeopardised by financial cuts resulting directly from the Covid-19 crisis. The NTS is facing a funding crisis and has launched an emergency appeal to prevent laying off 60 per cent of its staff.

The depopulation of St Kilda is often portrayed as forced upon the islanders by circumstance, that life had become too difficult. History suggests otherwise. ‘The whole narrative of a decline and fall isn’t borne out by the evidence,’ says Grant, ‘if you look at the population figures they remain very steady up until the First World War, which was in fact boom times for the St Kildans. Our own society views places like this as remote, marginal, peripheral. In fact, for most of the time that humans have been in Scotland, coasts and islands have been the most attractive places to live.’

Even though work would never have been less than hard, the temptation to over-sentimentalise the islands is not restricted to modern-day travellers. Just as the St Kildans left, the Scottish Office was receiving – and rejecting – 400 requests from UK citizens wishing to replace them. By 1930, however, a key factor had emerged that finally tipped the scales against remaining. In the wake of World War I, living standards were rising and the government was increasingly providing services such as health care and education, which were difficult to deliver on St Kilda. ‘Several families clearly felt,’ says Grant, ‘perhaps for the first time, they were likely to be better off elsewhere.’