But restoration could unlock one of the world’s most powerful nature-based climate solutions

By

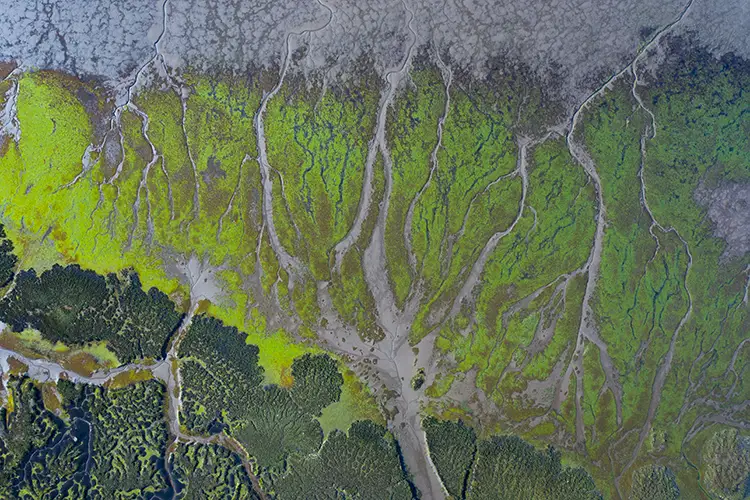

Saltmarshes – vital but often overlooked coastal ecosystems – are disappearing at an alarming rate, undermining progress on climate goals and weakening natural coastal defences. That’s the stark warning from a new global report published by WWF and Sky in collaboration with the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH) and Blue Marine Foundation.

The State of the World’s Saltmarshes report reveals that these tidal wetlands now cover just under 53,000 sq km – less than half of their historic range. Between 2000 and 2019, the planet lost more than 1,435 sq km of saltmarsh – an area twice the size of Singapore – and the decline continues at 0.28 per cent per year. That’s three times faster than the rate of forest loss.

A vanishing ecosystem

Saltmarshes, which sit between land and sea, are among the planet’s most powerful natural carbon sinks. They store carbon at rates that can exceed those of tropical rainforests, absorb wave energy, and serve as vital biodiversity habitats and flood defences. But decades of drainage, diking and coastal development have reduced them to a shadow of their former scale.

The report traces the history of this loss. As coastlines were reshaped to feed, house and connect growing populations, saltmarshes were drained for farmland, shrimp ponds, ports and cities. Now, their continued degradation is not just a loss for nature – it’s actively releasing carbon back into the atmosphere and threatening frontline coastal communities.

Room for recovery

Despite the losses, the report is not without hope. It identifies up to 2 million hectares (20,000 sq km) of saltmarsh that could be restored globally. In parts of the United States, northwest Europe, China and Australia, restoration efforts are already showing promise.

‘Saltmarshes are doing a lot of the heavy lifting for the climate with little recognition,’ said Tom Brook, oceans specialist at WWF-UK. ‘They’ve been reduced to a fraction of their former range – but with the right support, we can turn the tide.’

‘These efforts are not just symbolic,’ he added. ‘They are starting to add up and momentum is building. The next chapter for saltmarshes could be one of recovery and renewal – delivering carbon storage, storm protection, biodiversity and community resilience, all at once.’

Fiona Ball, Sky’s Group Director for Bigger Picture and Sustainability, underlined the importance of saltmarsh conservation to the UK: ‘Given the potential of saltmarshes to sequester carbon and serve as natural flood defences – and the role of the UK as home to one of the largest saltmarshes in Europe – we’re delighted to be helping WWF raise awareness.’

Five key recommendations from the report

- Elevate saltmarshes in national plans – Include them in climate and biodiversity strategies as carbon sinks and flood defences.

- Invest in restoration – Back large-scale saltmarsh recovery through public and private finance.

- Close data gaps – Especially in the Global South, where monitoring is weakest. A ‘Global Saltmarsh Watch’ is recommended.

- Integrate saltmarshes into global ocean goals – Including the 30×30 conservation target and relevant UN frameworks.

- Raise awareness – Recognise saltmarshes for the climate, ecological and cultural services they provide.

Why saltmarshes matter

Saltmarshes aren’t just carbon stores – they are ecological linchpins. They support rare and migratory species, act as nurseries for fish, filter water, protect coastlines and offer vital resources for human communities. With the climate crisis accelerating, saltmarshes may be among our best natural allies – but only if we act in time to preserve and restore them.