New and innovative techniques were used to produce detailed and beautiful maps of the region around Everest prior to attempts to reach the summit

By Katherine Parker, Images from the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

From their inception, Western encounters with the mountain now called Everest were intimately tied to visualising and integrating it into the developing mapping of the region. To climb the mountain, one had to know it – its height, its approaches, its composition, crags and crevices. Recording the geography of Everest is a process that involved various individuals and continues to this day, thanks to the changeable nature of mountainous terrain and the alterations wrought by increased human interaction and climate change.

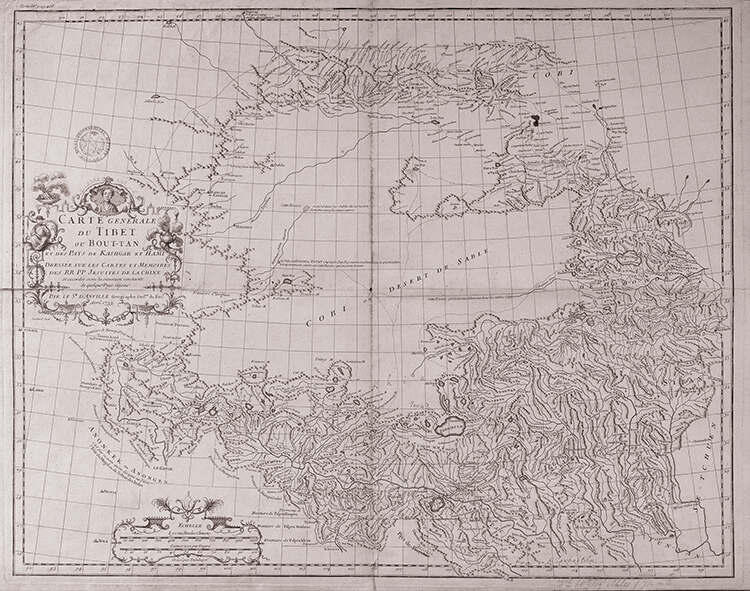

Tibetans, Sherpa, Bhotiya and people of different mountain ethnicities have known and interacted with the mountain for centuries, and it continues to hold a position of religious importance for local peoples. Tibetans knew the peak as Chomolungma, while it was Sagarmatha to the Nepalese. The Chinese were also familiar with the region; they surveyed the area (1708–16) and the mountain appears as part of a group called Jumu Lungma Alin on a Jesuit map (1717–18) based on these observations. French geographer and cartographer Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon D’Anville then integrated information from this survey into the first European map of the area, Carte Générale du Tibet ou Bout-tan et des Pays de Kashgar et Hami (1733).

The British were captivated by the High Himalaya, and particularly with precisely how high it was. James Rennell, surveyor general of Bengal in the late 18th century, carried out a comprehensive survey of large parts of India in the 1770s and suggested that the mountain range was taller than the Andes, then considered the most substantial in the world. Rennell’s survey led to the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS), an imperial project that sought to make South Asia physically and intellectually accessible to colonialists via a grid of precise measurements.

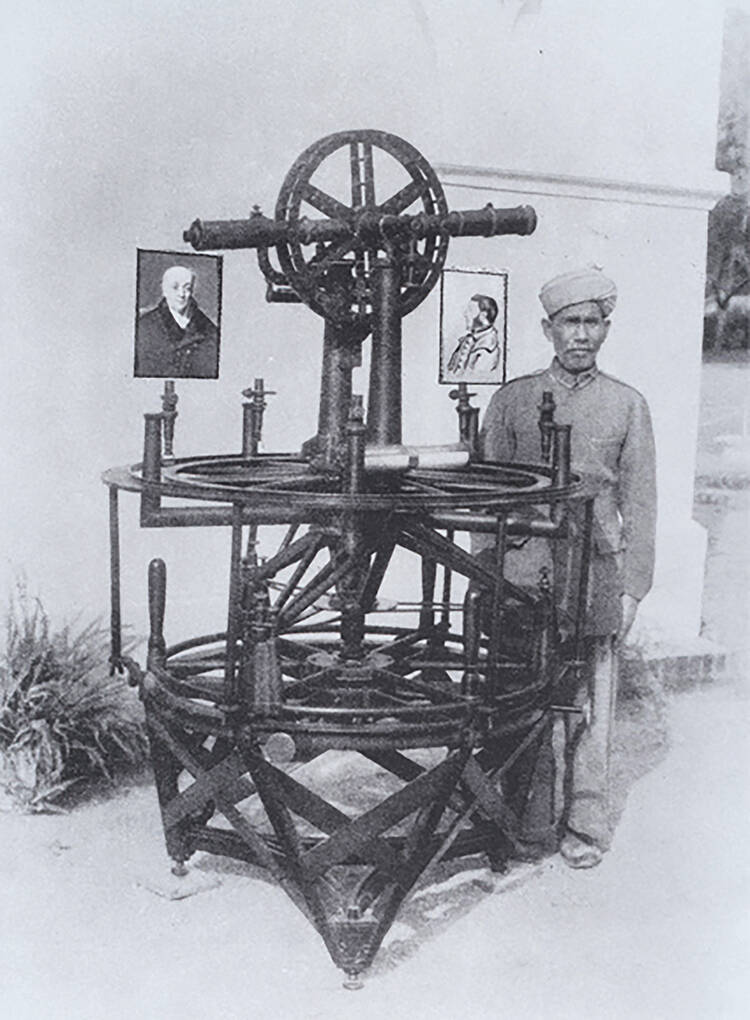

Labelled by Clements Markham, president of the Royal Geographical Society from 1893 to 1905, as ‘one of the most stupendous works in the whole history of science’, the survey began its work in Madras, in 1802, under the leadership of British surveyor William Lambton. Lambton’s interest was geodesy, the study of the precise shape of the Earth, and his aim was to measure its curvature by a process known as ‘triangulation’, whereby a baseline between two points, usually about seven miles apart, was measured using a chain of precisely known length mounted on wooden trestles. Then, from each of the two points, the angle between the baseline and the sight-line to a third point was measured using a theodolite, a surveying instrument that measures both vertical and horizontal angles. George Everest, a young artillery officer, joined the GTS as assistant to Lambton in 1818, and on the death of Lambton in 1823, took over as superintendent. He was later also appointed as surveyor general of India.

Everest continued Lambton’s work and completed what became known as ‘Lambton’s Great Arc’, a geometric web of triangulations that ran the entire length of the Indian subcontinent to the Himalayas. GTS surveyors would observe peaks from multiple stations, allowing them to claim with considerable accuracy which was the highest. Many of these surveyors and calculators were Indian in origin – known as pundits, they secretly explored regions north of British India.

The chief computer Radhanath Sikdar, a Bengali, reported that their observations indicated that a little-known peak was probably the tallest in the world. The GTS surveyors numbered the plethora of mountains they saw and also attempted to learn their local names. For the highest, called Peak XV, their limited network missed references to a local name, however.

This led Andrew Waugh to suggest in an 1856 letter to the president of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Roderick Murchison, that the mountain identified by Sikdar carry the name of Everest, Waugh’s predecessor and former superintendent of the GTS.

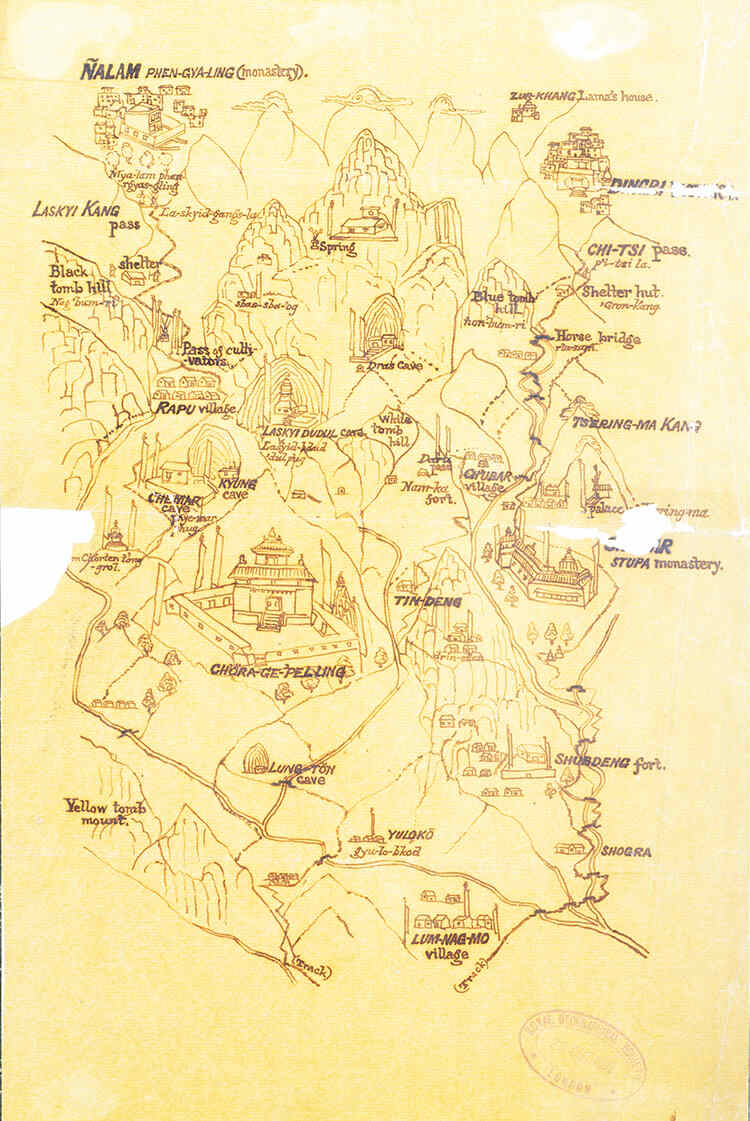

The pundit surveyors of the GTS initially surveyed the Eastern Himalaya because Westerners were barred from much of the region. These highly trained Indians had to conduct survey work while trying to blend in as traders or lamas (holy men). For Everest, one of the most important of these surveyors was Hari Ram, who first circumnavigated the mountain without specifically noting it. Later, small groups of Europeans managed to approach the mountain and its surroundings. For example, in 1904, as part of the military expedition to Lhasa led by Sir Francis Younghusband, Charles Henry Dudley Ryder, Cecil G Rawling, Frederick M Bailey and Henry Wood surveyed the Kara La pass, photographed the mountain and confirmed Everest’s status as the highest peak in the world. The immediate environs of the mountain, however, remained unrecorded.

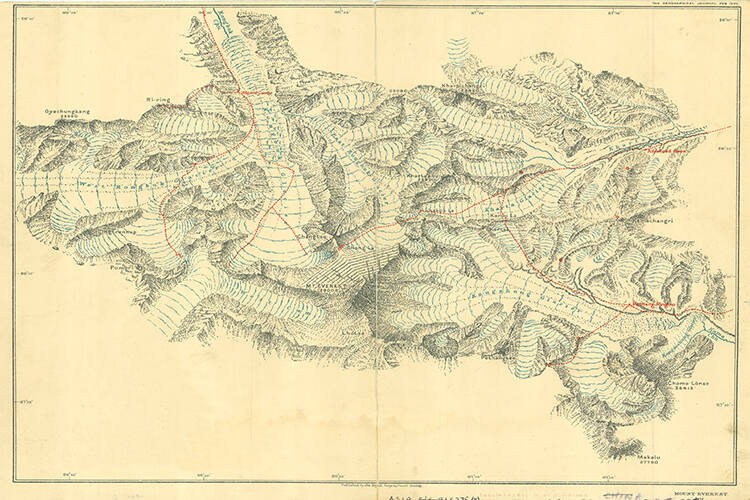

The first large-scale concerted effort to reconnoitre the mountain itself came in 1921, when the Dalai Lama gave permission for the mountain to be surveyed in anticipation of an attempted climb the following year. Led by Colonel Charles Howard-Bury, the expedition mapped an area the size of Switzerland, performing a general survey at four miles to an inch and a detailed survey of the approach at one mile to an inch. They were attempting, in Michael Ward’s words, ‘one of the last great prizes of mapping and mountain exploration’.

The survey party of Lalbir Singh Thapa, Gujjar Singh, Turubaj Singh, Henry T Morshead, Edward O Wheeler, the photographer Abdul Jalil Khan and 16 porters took careful observations and records. They produced a high-resolution map in three sheets at one mile to an inch, showing the mountain’s glaciers and possible routes to the top from the north, as well as a high-quality photographic collection. The 1922 and 1924 expeditions both relied on and expanded the work of the 1921 Mount Everest Reconnaissance Expedition. Hari Singh Thapa was the surveyor on the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition, adding his own observations to that of his predecessors. In particular, he led surveys of the Gyachung Kang Glacier and the area east of the Rongbuk Monastery; he then surveyed the head of the West Rongbuk Glacier as well, in a team accompanied by skilled climber John de Vars Hazard. Examples of his hand-drawn contour sketch maps are in the collections of the Society today, along with the printed maps to which he contributed.