Rory Walsh on the slow transformation of Manchester Docks into a media and arts hub

Trail • Urban • North West England • Guide

A breeze tugs at my coat when I get off the tram. Across a large plaza, the glass façades of the BBC buildings shimmer in the morning sun. After waving back at Pudsey Bear near the entrance, I pass the Tardis in the lobby, dodge a Dalek, then pause by the EastEnders bench. The black leather Mastermind chair is surprisingly comfy but not as much as the red BBC Breakfast sofa. On the desk in front of it are two large mugs. I reach to pick one up. It’s stuck down, another prop. At Salford Quays nothing is as it seems.

‘There is a theme-park, fairytale feel,’ says Angela Connelly, senior lecturer in the School of Architecture at Manchester Metropolitan University. Connelly regularly visits Salford Quays, especially the research library at The Lowry. ‘I led a walk here for the Twentieth Century Society,’ she continues. ‘Reaction was quite varied. Some people liked what they saw; others hated it. They said it was fake, or postmodern – in architecture that’s often a derogatory term.’

Salford Quays includes houses, museums, shops, galleries and the television and radio studios of MediaCityUK. Before the pandemic, around 7,000 people worked at MediaCityUK for more than 250 companies. On MediaCityUK Bridge, Connelly and I take in the view. A few puffy clouds hang in the pale blue sky. To our right stands the origami outline of the Imperial War Museum North. Opposite, on our left, is The Lowry’s geometric puzzle. Between them and below us lies the expanse of the Manchester Ship Canal.

As recently as 2007, we would have been overlooking scrubby brownfield land used mainly for car parking. A century earlier, the scene would be different again. From the early 1890s to the early 1980s, the quiet stretch of water below us was full of ships. Salford Quays was part of the Manchester Docks. During their prime, Manchester was Britain’s third-largest port, after London and Liverpool. This was despite being almost 65 kilometres inland. Salford Quays’ surreal feel can be traced to the docks’ strange location.

As we follow the canal, Connelly relates how the docks developed. ‘By the 1840s, Manchester’s cotton industry was booming. But the city was landlocked and relied upon coastal ports for trade. The nearest was Liverpool, almost 50 kilometres away. Manchester’s leading businessmen thought Liverpool’s fees were too expensive. So, they suggested building an inland port, using a canal to bypass Liverpool.’

After decades of debate, the Manchester Ship Canal opened on 21 May 1894. From the Mersey, ships cruised along it through 58 kilometres of rural Cheshire and Lancashire. The Ship Canal gave Manchester direct access to the Irish Sea and beyond. The docks soon carried more than a million tonnes of cargo per year. ‘In the 1920s, a guidebook called the Seven Wonders of Manchester was published,’ Connelly continues. ‘The Ship Canal was number one.’

However, the Ship Canal wasn’t the success that the investors hoped. A speed limit restricted traffic and ships often left empty. A decisive change emerged in the 1960s: containerisation. Containers reduced the need for armies of dock workers to handle cargo. They also encouraged ships to grow larger. The Ship Canal became too expensive and too small. The Manchester Docks shut in 1982, making 3,000 people redundant. Local geography opened the docks, global geography closed them.

The trail explores what happened to the area next. Yet even the modern landmarks dredge up the past. The startling Imperial War Museum North stands on a bomb site; the docks were hit during the Manchester Blitz. The museum also lines the edge of Trafford Park, Europe’s first planned industrial estate. The Traffords were wealthy Norman landowners. By the 1890s, their grand mansion stood in a 400 hectare deer park. When the Ship Canal opened beside it, the family sold up and moved out. Bizarrely, deer still roamed the site until 1900. Workers spotted them during lunch breaks.

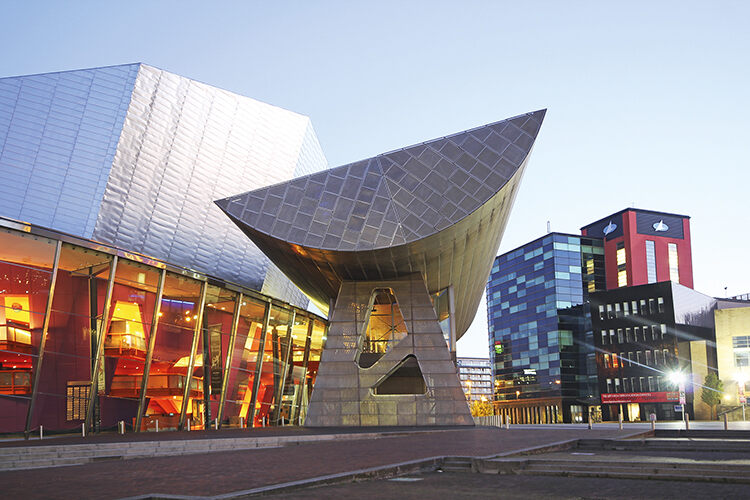

Imperial War Museum North isn’t the only eye-catching building at Salford Quays. After crossing the Ship Canal at Lowry Bridge, we stop outside The Lowry arts centre. Named after Salford-born artist LS Lowry (1887–1976), the building contains a theatre, cinema, galleries and a permanent archive of his work. Connelly and I agree that it would be interesting to hear his thoughts about it. The silver-clad structure looks like a stack of cubes next to a giant animal feeding trough. ‘It’s deliberately unusual,’ Connelly reveals.

‘When the first regeneration plans for the docks were published in 1988, the Lowry was the centrepiece. It was intended to be Salford’s Guggenheim, drawing comparisons to the similar building in Bilbao. The aim was to recreate the Bilbao Effect, using a landmark venue to attract visitors and developers.’ The Lowry opened in 2000, a dozen years after the initial concept. Besides taking a long time, it feels a long distance from other attractions at Salford Quays. One reason is the former docks’ sheer size. Another is how they were developed.

‘When the docks closed, Salford City Council bought the land,’ Connelly explains. ‘The London docks, meanwhile, were privately developed. There, the owners could masterplan their own schemes. At Salford Quays, the docks were cleared then stood empty for years. The council couldn’t afford to develop them. When buildings such as the Lowry and the War Museum arrived, they stood alone and isolated. It took ages to fill the gaps.’

Discover more about Britain…

Among the first arrivals were housing. Beside the basin of Dock 9, we pass 1980s red-brick homes. Dominating the area, however, are luxury flats, including the sail-like fronts of the NV Buildings. As we stand in their shadow, Connelly says, ‘What interests me is Salford’s relationship with central Manchester. Salford is a very deprived council ward, while Manchester is a big investment hub. Some of my colleagues have researched if there is any trickle-down effect, whether Salford benefits economically from Manchester’s success. The jury’s out.’

Connelly has mixed feelings about Salford Quays. ‘The social and economic aspects probably haven’t worked out as planned,’ she suggests. ‘But environmentally, it’s been a big success. Regenerating brownfield instead of building on virgin land, cleaning up the water … The docks were very polluted. Chemicals in the air, appalling water quality and terrible smog. People tell stories about feeling their way along walls to get around.’

Today, plants and fish live in the surviving dock basins. Salford Quays has even been awarded Blue Flag status, a title usually reserved for the cleanest beaches. After completing the trail, Connelly shows me photos of the Ship Canal being built. They could be scenes from a battlefield. Men and boys caked in mud line up for the camera in a deep trench. ‘Around 16,000 navvies built it, mainly by hand; 130 of them died, hundreds more were badly injured,’ Connelly recounts. ‘The Ship Canal was regarded and promoted as a great achievement, but the human cost is often forgotten.’

The Ship Canal was radical and controversial when it opened; Salford Quays divides opinion today. In the afternoon dusk, the canal’s surface looks calm and quiet. Still waters run deep, however, in this area transformed, not once but twice.