Global population is set to peak in mid-2080s, then undergo a dramatic decline. Mark Rowe reports on the consequences of such a seismic shift

Not since the Black Death in the 1300s has the total number of people living on Earth declined. We had been around for roughly 300,000 years by then and numbered about 450 million before the plague swept the Earth, and 350 million afterwards.

By 1803, we had reached one billion. By 15 November 2022, that number had swollen to eight billion, and we should pass nine billion in 2037. Only, according to the UN’s 2024 World Population Prospects, after hitting ten billion in the mid-2080s, does the staggering growth of Homo sapiens peak and start to go into reverse.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

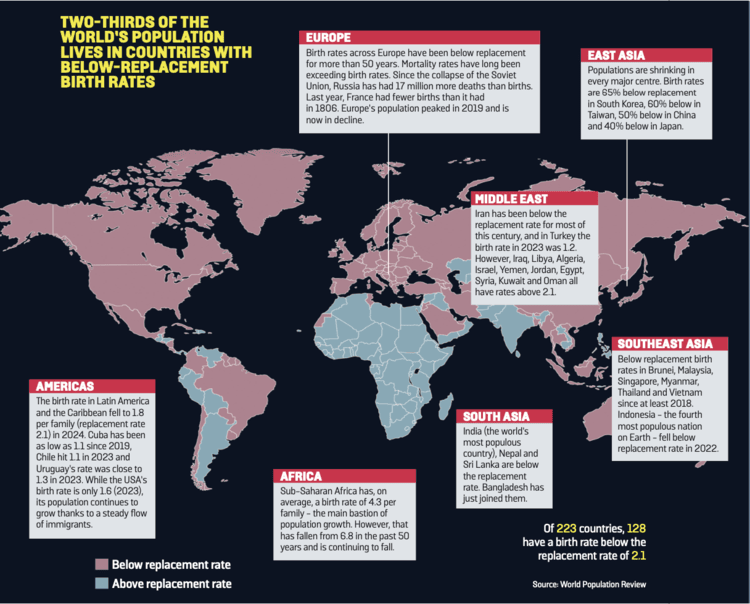

However, it’s a complex picture, and while we face a further 25 per cent growth in our ranks globally, there are many countries where the decline has started.

‘Most places in the world have below replacement fertility rates (less than two children per woman on average), but there are a handful of countries with continued high fertility rates,’ says Jennifer D Sciubba, president of the Population Reference Bureau. ‘There is both a trend towards shrinking countries and some countries that have young age structures and are still growing over the next several decades.’

Falling fertility rates across much of Europe, large swathes of Asia and most of the Americas are one factor. A counterweight is improving life expectancy. Globally, average life expectancy at birth reached 73.3 years this year, an increase of 8.4 years since 1995 and will rise to 77.2 years by 2050.

‘It’s good news,’ says Patrick Gerland, chief of the Population Estimates and Projection Section at the UN’s Population Division. ‘People in many countries are living longer, healthier lives.’ The list of largest nations is going to look different by 2100.

For now, India and China each represent nearly 18 per cent of the world’s population but are on divergent courses. India overtook China as the world’s most populous nation in 2023 and by 2100 will be comfortably the largest country, with a population of 1.5bn (up from 1.45bn today). China will still be the second largest nation but will have declined from today’s 1.42bn to 638m.

Phenomenal growth will see dramatic changes in the pack behind these two behemoths. Pakistan looks set to be the world’s third most populous nation, growing from 299m today to 510m, followed by Nigeria (rising from 230m to 477m) and Ethiopia (130m to 366m). Some other African nations will also see rapid growth, including Egypt (115m to 202m), Angola (38m to 150m), Sudan (50m to 137m), Kenya (56m to 104m) and South Africa (63m to 96m), Niger (26.5m to 90.6m) and Ghana (34.1 to 67.5m). As a whole, the African continent will increase from 1.5bn to 3.8bn.

Further east, Afghanistan will grow from 38m in 2020 to 106m in 2100. Some Middle Eastern states will also see high population growth, often from migration: Saudi Arabia is projected to grow from 33.6m to 71m, war-torn Yemen is on course to swell from 40m to peak at 110m at the end of the century. The UAE, too, will double from 10.8m to 26m.

Across the planet, however, such stellar growth rates are becoming the exception, for population growth is already losing momentum. ‘The world population is expected to peak,’ says Gerland, ‘it’s just a question of to what level and how fast that peak and the decline will be.’ In 63 countries and areas, containing 28 per cent of the

Who really gets to choose?

The UN’s 2024 population report found that, in 2023, 4.7 million babies, or about 3.5 per cent of all worldwide births, were born to mothers under the age of 18. Around 340,000 were born to girls under age 15, with all the attendant risks and serious consequences for the health and well-being of both the young mothers and their children.

Meanwhile, the State of World Population report found that 44 per cent of partnered women are ‘unable to exercise bodily autonomy’, which, in plain English, means they’re unable to make their own decisions over their health care, contraception and whether or not to have sex. Half a million births every year are to young girls 10–14 years old; nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended; and as few as 25–30 per cent of women in low- and middle-income regions are having the number of children they planned, at the speed that they planned (‘if they even planned on having them at all’, says the report).

‘Human reproduction should be a choice, but the latest data show us that, tragically, it often is not,’ says a UN Population Fund spokesperson. ‘When faced with population changes or concerns, we often see rhetoric and policymakers turn to fertility rates as a preferred solution. How often do people proposing these solutions consider the fertility desires of women and girls? Not often enough.’

The UN 2024 report was unequivocal in its conclusions, noting that ‘discrimination and legal barriers limit women and adolescents’ access to sexual and reproductive health services.’ Raising the legal marriage age and integrating family planning into primary health care are, it says, essential to enhancing women’s education and economic participation, and reducing childbearing.

world’s population in 2024, the population has already peaked. In a further 48 countries and areas, with ten per cent of the world’s population, populations are projected to peak by 2054. Beyond then, other large nations start to shrink: Indonesia (282m in 2024) peaks around 332m in 2062 and drops to 296m by 2100; Brazil has grown rapidly, from 52m in 1950 to 210m today, but will drop to 163m by 2100. This also includes India, for, while growing fast, it’s already ageing, and a peak of 1.7bn is inked in for 2080.

‘There are countries that are going to lose more than a fifth of their population within the next three decades (until 2050) and 40–50 per cent by the end of the century,’ says Anne Goujon, population programme director for the Centre of Expertise on Population and Migration at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna. This is throwing up some extraordinary projections. Unless something changes, countries such as South Korea (51.7m – and already declining – to 22m in 2100 ), Japan (124m to 77m), Romania (19m to 10.8m), Poland (39m to 19m) and Cuba (11m to 5.6m) will be whittled to shadows of their present stature.

Europe (with exceptions) is already declining and set to drop from 745m today to 593m.

Better healthcare, more education, fewer children

The drivers of population trends and longevity are as varied as the population data itself. ‘The story is somewhat complex; the world is not homogeneous and reflects changes at regional, country and local levels,’ says Gerland.

‘As countries get richer and women get better access to health and education, fertility rates begin to fall – it’s a phenomenon seen across the world.’ The replacement level required to keep a population stable in the long run without migration is 2.1 children per family: in 1968, women averaged five or more children in 120 out of 200 countries; today, just eight nations report that fertility rate. The global fertility rate stands at 2.3 live births per woman, and more than half of all countries and areas have rates below replacement level.

‘For countries that are increasing in size, the reason is mostly due to population momentum – having a large population base, slowly declining fertility and increasing survival of children,’ says Goujon. ‘But the main story is not just about fertility but also progress in fighting child and infant mortality.’

Changing cultural norms and greater opportunities for women are significant factors. ‘The trend from high fertility to low fertility is influenced by rising education for girls, especially opportunities to work outside the home, especially for girls, and reduced child marriage,’ says Sciubba. ‘The trend from low to even lower fertility is driven by factors such as rising costs of housing and childcare, and a shift in values away from having children.’

Does size matter?

Will China’s population decline, India and Nigeria’s demographic increase and Russia’s decline (from 145m today to 126m by 2100) drive a sea change in geopolitics? John Wilmoth, director of the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, thinks so, declaring: ‘I think you have certain claims on things [by being the country with largest population].’

‘Perhaps just as important for influence is the ‘demographic dividend’, says Guillaume Marois, research scholar at IIASA’s Population and Just Societies, ‘whereby the share of the elderly remains low, the share of the working-age population, which produces more than it consumes, increases, giving the country an economic boost.’ Countries that can expect this dividend in the coming decades include not only India but Nepal, Bangladesh, Turkey and Brazil.

‘Population size is certainly related to global influence, but it is not enough,’ adds Marois. ‘China was the most populous country in the world for the whole of the 20th century, but its influence only began to rise sharply when the country became a major player in international trade.’

The sceptical view that it takes more than population heft to address international power imbalances is shared by Sciubba. ‘Rights and influence are two very different things,’ she says. ‘Look at who sits on the UN Security Council. Maybe [size matters] for influence, if your economy is also huge like China’s, but companies don’t just go to where there is labour – they go to stable government, a nice place to live, an open business environment.’

Future fears

While the global population peak is some 60 years away, population decline is already exercising governments.

According to IIASA, by the mid-2030s, those aged 80 and over will reach 265 million, outnumbering infants. ‘Pensions systems that relied on increasing numbers of workers each year to support retirees will be strained or insolvent unless reformed,’ says Sciubba. ‘There will be continued demands on healthcare.’

The European Union is one such area, where more than 30 per cent of the EU population is expected to be 65 or older by 2100 and the 91–100-plus age group to more than double. ‘Over recent decades, the EU has been shaped by population growth, but now its population is ageing, moving towards longer- living, lower-fertility and higher-educated societies,’ says Marois.

‘This demographic shift could have a significant impact on the region’s economic prospects,’ says Marois. ‘Who will live and work in Europe in the coming decades? How many, and with what skills?’

Trying to nudge a population to have more or fewer children is, says Gerland, akin ‘to something of a thought experiment’. The sticking point is that no reasonable government would compel it citizens in one direction or another. In its 2023 State of World Population report, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) points out: ‘In general we see efforts to influence fertility are correlated with lower performance on measures of democracy and human freedom. You can’t tell people what to do – only influence them… There is no perfect number of people, nor should we prescribe a number of children that each woman should have. History has shown the damage this kind of thinking can cause, such as eugenics and genocide.’

Yet many countries faced with ageing populations feel the need to do something and the UNFPA acknowledges that not all policies are coercive: ‘In the past couple of decades, the trend has been to try to empower people with choice, give them the chance to have more children if they want them. This means providing information on family planning and access to greater education for girls.’

For many states, migration is the go-to option. North America, for example, faces the same demographic pressures as Europe but the USA (344m now, 421m in 2100), Canada (39.5m to 53.5m), along with Australia (26.5m to 43m), are likely to maintain their working-age populations through net immigration, according to the UN report.

Yet migration will only ever be part of the answer, says Goujon. ‘Migration can help momentarily, but in order to compensate for a declining workforce, a country needs constant flows of migrants, as migrants age or return to their host country as they age.’

In reality, for most countries, it’s unsustainable to indefinitely replace their population through migration, says Gerland. ‘So, either that country shrivels, or its values change in relation to the number of children people have.’

The holistic approach

Low fertility rates are rarely attributable to one factor. ‘Almost all studies show that people want to have one or more children,’ says Gerland, ‘but work practices, a lack of childcare, mean they stick with zero or just one.

Paying people more is not enough – it needs a combination of holistic and local actions – local child care, maternity and paternity leave, flexible work patterns, housing and transport – measures that aren’t just for a few months but support the family until the children grow up. If you force people to choose between a career and a family, you eventually get a bottleneck.’ France, Switzerland and the Nordic countries are nations that ‘manage to get close to the replacement level by implementing such policies,’ says Gerland.

When nations address only some, or none, of these issues, the population can fall off a cliff, says Gerland, a prospect facing South Korea, where the fertility rate is 0.72 per woman, the world’s lowest. Over the past 20 years, the government has spent US$270 billion on incentives, including cash subsidies, babysitting services and support for infertility treatment – to no avail.

Cultural mores, including a large gender pay gap, long working hours and an expectation that women are mainly responsible for household chores and childcare, seem hard to unpick.

South Korea’s sex bias

In South Korea, as well as some other East Asian nations, there has historically been what the UN’s Patrick Gerland describes as ‘a strong son preference’ – if you are only going to have one child, then it has long been seen as desirable for that one child to be a boy.

‘Unfortunately, in some cases, there has been an over-use of sex selection,’ he says. Naturally, around 1-2 per cent more boys are born than girls around the world, but in South Korea, says Gerland, ‘this became distorted to the extent you were getting 10-15 per cent more boys’.

However, in the past decade or so, this cultural trend has begun to dissipate, with population data suggesting the sex ratio is returning to a natural balance. ‘A lot of families are preferring a girl, or keeping the girl when they see a scan,’ says Gerland. Partly, he suggests, this is to do with a recognition of the impending reality of mass population ageing – just who is going to look after elderly parents?

‘Usually in Korean society, it is the girl that does the caring rather than the boy. It shows how future unknowns can impact, overcome and change cultural norms. You think things will never change but this shows the importance of not giving up; strategies and positive messaging can shift minds very quickly – in just a few years.’

‘The country is facing a steep and potentially dystopian decline with huge and serious impacts,’ says Gerland. ‘There’s a new reality. It’s not just about money. Right now, culturally, the workplace makes it very hard for anyone to combine a family with work, it’s making people choose between them.’ There may be signs that attitudes are finally changing.

Human-induced environmental impacts range from climate change to deforestation, water over-extraction and a shocking decline in biodiversity. Population changes – up or down – reflect these pressures. According to the International Energy Agency, by mid- century, energy demand in Southeast Asia will overtake that of the EU. Despite this, Gerland is relatively sanguine for the long term and points out that the Earth appears able to feed eight billion people, if not always easily. ‘We do not see the huge famines of the past – where there is famine, it is usually political,’ he says. ‘We are seeing huge advances in agro-economics, global trade, crop yields.

‘Some people hold the view that the fewer people, the better for the planet,’ he adds, ‘but it is more complex than that. If the whole world produced and consumed like the West, it would definitely be a problem, but it clearly does not.’

The choices ahead

Demographics have long lead-in times, but any assumption that governments across the world are applying judicious long-term insight to the unfolding scenarios might be naïve, says Sciubba. ‘You can absolutely see the future with demographic trends, but not all political systems are set up to do long-term planning. Democracies can struggle to see past the next election cycle; non-democracies may be fragile and unable to plan long term.’

Yet Sciubba remains optimistic. ‘Each society should debate what kind of migration works best to fit their needs, whether they desire a humanitarian-centric migration regime, one that reunifies families, or one that fills skills gaps in the workforce,’ she says. ‘Yes, [countries] will shrink. I can’t see any reason why they won’t still function.’

For anyone looking at South Korea and wondering if it could happen in their own country, Gerland has an unsettling message – it’s almost certainly already unfolding.

‘In most industrialised nations, we have seen an exodus from the rural to the urban, you have regions, pockets, that are dominated by older people who face issues over who will care for them if there are not enough younger workers. This starts at a local level and eventually becomes a national issue.’

After the peak, what next? Marois describes the growth of recent centuries as ‘exceptional and unsustainable’ but takes a longer-term view. ‘Even in sub-Saharan Africa, fertility rates are falling every year and should catch up with the rest of the world sometime in the 21st century,’ he says. ‘In the future, we will probably return to a normal regime of alternating slow growth and slow decline.’