At the centre of world trade, Singapore is an affluent global power. However, as Katie Burton reports, its economic rise has come at a political cost

Some countries are born geographically lucky; Singapore is one of them. Occupying one main island and 63 islets, it rests on the very southern tip of the Malay peninsula, offering a haven to passing sailors with an interest in getting from East to West, or back the other way.

Long before the British – under colonial official Stamford Raffles – realised its potential as a trading port and drew it into the British Empire in the early 1800s, the island now called Singapore served as a hub for a variety of maritime empires.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

Modern-day Singapore hasn’t forgotten this. Its state-owned investment company, reported to be the sixth-largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, is called Temasek, in homage to a settlement believed to have been in place in the region as far back as the 13th century. The name is potentially derived from a Malay word meaning ‘lake’ or ‘sea’. Recent discoveries have only added to the notion of the island being a vital and successful hub for trade at this time.

In 2015, a shipwreck dating from the mid-14th century was discovered off Singapore’s coast. It yielded four tonnes of ceramics and other artifacts, including beautiful blue- and-white porcelain characteristic of the Yuan-dynasty, which ruled China between 1279 and 1368.

Today, Singapore’s geographical position is no less relevant. According to the 2024 Leading Maritime Cities report, the city-state tops the bill as the world’s premier maritime city. Its port is the world’s second-busiest in terms of total shipping tonnage and it’s connected to another 600 ports globally. Every day, around 1,000 ships transporting fossil fuels, loaded with cars or piled high with shipping containers crammed with all manner of goods, are handled at the 15-kilometre quayside.

This all goes some way to explaining why Singapore is so wealthy – and, by any measure, it’s very wealthy. By GDP per capita, it’s the fourth-richest country in the world,

a metric that has doubled in real terms over the past 20 years. At around US$46,000, Singaporeans’ median full-time wages of are now higher than those in Britain, where they sit at around US$44,000. But geography doesn’t explain everything.

Many comparatively blessed nations, some of them Singapore’s direct neighbours, have failed to reach the city-state’s dizzying heights of prosperity. Somewhere in its history, Singapore got something right.

Fact File

Area

Singapore is one of the world’s smallest countries, made up of one main island and 62 smaller ones covering 728.6 square kilometres.

Population

About 5.64 million (2023), giving it a population density of 7,772 per square kilometre – one of the world’s highest.

Fertility rate

An average of 1.15 children per woman is one of the lowest in the world. With such a low birth rate and a rising life expectancy, Singapore is ageing rapidly. Accoring to UN population projections the number of over-65s will increase by 21% between 2019 and 2050.

Ethnicities

Chinese 74.3%, Malay 13.5%, Indian 9% and other groups 3.2%.

Languages

The country has four official languages: English (widely used for business and education), Mandarin, Malay (national language) and Tamil.

Religions

Buddhism (31.1%), Christianity (18.9%), Islam (15.6%), Hinduism (5%)

Education

The literacy rate stands at more than 97%. It tops world education tables in maths, science and reading. In 2015, both its primary and secondary students ranked first in the OECD’s global school performance rankings across 76 countries.

Land use

Agriculture 1%, forest 3.3%, urban 95.7%

Healthcare

The government-run system, along with an extensive private insurance programme, is considered a world leader. Singaporeans currently have the world’s highest life expectancy of 84.8 years at birth. Women can expect to live an average of 87.6 years, with 75.8 years in good health. The averages for men are lower, with a life expectancy of 81.9 years, with 72.5 years in good health.

Media

Despite being a popular base for journalists working in the region, reporting in Singapore itself is tightly controlled both in print, television and online.

Economic success

Much of the credit for Singapore’s modern-day prosperity has to be given to its leaders since it gained independence from Malaysia in 1965. This was a moment that marked the end of a hugely turbulent period. Singapore suffered heavily during the Second World War under Japanese occupation, the British having surrendered in 1942 in a defeat British prime minister Winston Churchill labelled ‘the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’.

The massacre that followed saw the deaths of 40,000–50,000 citizens, mostly from the ethnic-Chinese population, and much of its infrastructure was destroyed. With trust in the British deeply eroded, Singapore joined with Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak to form the new Federation of Malaysia in 1963, but relations between Singapore and Malaysia were so fraught that by August 1965, the government of Malaysia voted 126 to 0 to expel Singapore, leaving it as an independent country.

Ever since, Singapore has been dominated by one political party – the People’s Action Party (PAP) – and, to a large extent, by one family: the Lee family. The first prime minister after independence, Lee Kuan Yew, held the post from 1959 to 1990. Since then, there have been just three prime ministers, with the most recent, Lawrence Wong, taking over in May 2024 from Lee Hsien Loong, Lee Kuan Yew’s son.

From the very beginning, in the early 1960s, Lee Kuan Yew’s economic model was transformative. By emphasising economic growth, a low and transparent tax regime, a strong regulatory and legal framework, and a neutral diplomatic policy, he set the path the country still treads today – one that is open for business in every sense and has seen Singapore rise and thrive not just as a global maritime hub, but as an aviation and financial one, too.

Terrence Lee, a scholar of politics and communication and the dean of humanities and social sciences at the Sheridan Institute for Higher Education, explains that this economic model has been largely the same for the past 50 years. ‘Economically, the model for Singapore has always been to attract foreign companies to set up shop in Singapore,’ he says. ‘It’s that whole trading-hub mentality reinvented for the modern digital era. It wants to be a hub for as many things as it imagines will work, that will provide jobs for Singaporeans and bring in foreign investment from other players.’

Other policies established right from the off have also played a part in Singapore’s success. Bill Hayton, an associate fellow with the Asia-Pacific Programme at Chatham House, notes that Singapore’s leaders have always been responsive to the needs of its people. He explains that unlike in neighbouring Burma, which made a point of squashing and expelling minority communities, paving the way for decades of turmoil that continues today, Singapore embraced the idea of itself as a multiracial meritocracy from the moment of independence, and placed a high value on education. Also in contrast to its neighbours, Singapore has

– as the success of the Lee family indicates – been remarkably politically stable.

But, if all of this means that Singapore can sometimes be idealised in the West as a rich and happy utopia, that wouldn’t be quite right either. The very political stability that has helped the country economically comes with a price.

Timeline

1819 – Stamford Raffles, of the British East India Company, establishes a trading post on Singapore island.

1826 – Singapore becomes part of the British colony of Straits Settlements under the rule of the East India Company, together with Malacca and Penang.

1832 – Singapore becomes the capital of Straits Settlements. The port attracts thousands of migrants from China, India and other parts of Asia.

1867 – Straits Settlements become a crown colony of the British Empire.

1942 – Singapore falls to Japan during WWII. The Japanese military police kills an estimated 25,000– 50,000 people during the Sook Ching Massacre.

1945 – Japan is defeated and Singapore comes under British military administration. of Malaysia.

1965 – Singapore pulls out of the Federation of Malaysia, at Malaysia’s invitation. The territory becomes an independent republic.

1990 – Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew of the PAP stands down after 31 years, but continues to exert significant influence as senior minister.

2004 – Lee Hsien Loong, eldest son of the former prime minister, is sworn in as prime minister.

2015 – Singapore’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, dies aged 91. Tens of thousands of people line the streets to attend his funeral procession.

2024 – Lawrence Wong becomes prime minister.

Strong control

Singapore isn’t a thriving democracy – a fact that, in light of its prosperity, can sometimes be glossed over. Singapore does poorly on international rankings related to the strength of a state’s democracy or the freedom of its press. Freedom House, a US-based non-profit, gives it a score of 48 out of 100 for overall freedom, on par with Honduras (the UK gets 91), noting that the PAP utterly dominates the parliamentary political system.

‘The electoral and legal framework that the PAP has constructed allows for some political pluralism, but it constrains the growth of opposition parties

and limits freedoms of expression, assembly, and association,’ reads its report. ‘All domestic newspapers, radio stations, and television channels are owned by government-linked companies… The government uses racial or religious tensions and the threat of terrorism to justify restrictions on freedom of speech.’

Housing

Singapore has the third-highest population density in the world but has done well to cultivate an image as a highly livable city regardless. Its housing policy is particularly famous – a unique system in which more than 80 per cent of the population lives in public housing, often in high-rise apartment blocks.

The model is based on home ownership rather than renting, and sees citizens buy public housing flats using a state-run mortgage system. The framework includes policies aimed at ensuring social cohesion and diversity, with ethnic ratios set for every public housing block. The ratio corresponds to the demographic make-up of the country, which today is: 74 per cent Chinese, 13 per cent Malay, and nine per cent Indian, with the remainder accounting for all other nationalities.

Bill Hayton says that while the country does have elections (in the most recent general election of 2020, the PAP won 83 elected seats, with the opposition Workers’ Party winning ten), ‘broadly speaking, there’s a political consensus about how the country works, with the People’s Action Party running the country.

Anything that challenges that settlement faces a great deal of difficulty. The Workers Party is not banned, but the law has been used to suppress dissent and some overt criticism. It’s not done through thuggish means. It’s done by the use of libel laws and financial penalties, but they can be just as effective.’

It’s a similar story on freedom of the press. Reporters Without Borders, an international non-profit that ranks countries based on press freedom, states that: ‘While Singapore boasts of being a model for economic development, it is an example of what not to be in regard to freedom of the press.’ For 2024, it ranked Singapore 126th out of 180 countries.

Terrence Lee, who grew up in Singapore before moving to Australia in the late 1990s, notes that the government is aware of these kinds of reports and certainly doesn’t revel in them. Rather than addressing them directly, however, its approach is to re-direct observers to those areas where it does much better

in the rankings – and there are many.

Nevertheless, he notes that some of the country’s more repressive policies verge on the ridiculous. The government introduced a new ‘fake news’ law in 2019. Widely condemned by human rights organisations, it allows the state to dictate whether information is true or not and to tell online platforms to remove material it considers false. ‘Some of the policies are really, really far-fetched,’ says Lee. ‘The fake news law, for example, is blatantly applied to opposition politicians and activists.’

A few rather strange incidents in recent years have hinted at this more repressive side of the country. In particular, in October 2024, Lee Hsien Yang, the son of Singapore’s founder and the brother of the former prime minister, was granted asylum in the UK following claims of persecution from the Singaporean government.

While the facts are foggy, speaking to the news agency AP in 2024, he insisted that his case was more than a family feud, stating that: ‘For a rich, wealthy, affluent, developed country, you know, there’s a dark side to it. You see this shiny exterior, but beneath that, there is a repressive nature to that regime, and there are people fleeing from it. I’m the most prominent example of that.’

‘Singapore is a massive contradiction,’ adds Terrence Lee. ‘If you travel to Singapore, it’s utterly impressive. It’s an ultra-modern city, gleaming skyscrapers. I know lots of people absolutely adore Singapore, and I’m not saying it’s a bad place. But it’s behind a facade. I think you need to ask questions around what’s actually keeping this place ticking, politically, socially and so on.’

Business first for Asean

While relations with its neighbours, particularly Malaysia, have been troubled in the past, Singapore tends to focus on maintaining peace and economic cooperation with other Southeast Asian countries.

It is a key member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), an intergovernmental grouping formed in 1967 and comprised of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Singapore still places high importance on membership of ASEAN. According to Terrence Lee of the Sheridan Institute, it allows the country to continue to do business with the other members and dominate some of their industries. External commentators, however, tend to be fairly scathing.

ASEAN has been criticised for failing to respond to the civil war in Myanmar, while Bill Hayton from Chatham House describes its statement on the war in Ukraine as ‘characteristically bland’, though he acknowledges that the bloc has served its ultimate purpose: there hasn’t been a war between ASEAN member states since its inception. Singapore’s approach to ASEAN epitomises its business-first approach to international relations, one that mostly boils down to not rocking the boat.

‘It has that business mentality driving it,’ says Lee. ‘You’ve heard of “Singapore Inc.” It’s run like a mega-conglomerate.’

Given this, is it fair to say that we in the UK – with our historic ties to Singapore and successful business relationships – have a blind spot when it comes to Singapore’s politics? Hayton thinks this would be fair comment. ‘It’s a very congenial place to live and very well run, and has a strong rule of law, in the sense that power is wielded within a set of rules,’ he says. ‘But the governing elite doesn’t like people prying into the way that it works and it absolutely does not like criticism. So quite a few media organisations are based in Singapore, but they very rarely report on Singapore.’

Do Singaporean people mind these restrictions? Broadly speaking, it seems, not really. Hayton suggests that this is in large part due to the high standard of living most people enjoy. ‘There’s a classic deal there that the government delivers good incomes, health, housing and so on, so people mute their criticisms.’

He also points out that people in Singapore have long been used to a much higher degree of state intervention in their lives than we would be used to in the UK: you don’t miss what you’ve never had.

Lee, who still has family living in Singapore, agrees. ‘We’re talking about very educated people, right? Education levels in Singapore are really high by global standards. I think Singaporeans have realised that they are under one-party rule and that they don’t get the full liberties liberal democracies do.’

‘But they are economically well off – the average middle-class Singaporean family will go away almost every long school holiday, so they are a very well-travelled people as well. They kind of see that as something that’s of greater value than seeking liberties. That sort of thinking pervades, I think, the country.’

Navigating the world

If Singapore has been, and continues to be, economically successful, with little internal dissent and glowing economic statistics, that’s not to say there are no challenges ahead. Jürgen Haacke, an associate professor in international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science, points to increasing big-power rivalry as a challenge for Singapore. While China is Singapore’s largest trading partner, it has military ties with the USA, which also accounts for more than 20 per cent of all foreign direct investment in Singapore. Like many other small states, Singapore must, therefore, seek to maintain good relations with both.

The fact that 70 per cent of Singapore’s population is ethnic Chinese lends a unique element to this balancing act, but it doesn’t mean it naturally has closer ties with China.

In fact, Singapore is rigid in defending its status as a multi-racial country with its own identity and, in some areas, particularly defence, it’s clearly closer to the USA. ‘Singapore has historically always been very careful as far as ethnic Chinese identity is concerned,’ says Haacke. ‘And you see that also in contemporary times quite clearly, because if there was a suggestion on the part of some Chinese academics, perhaps even officials, that Singapore might think more in Chinese terms, the retort usually tends to be that now there is a separate Singaporean identity that pays due regard to the multicultural identity of the city state.’

Overall, the country maintains its balancing act very successfully, and insists that it isn’t passive in doing so. In an interview with The Economist in May, then deputy prime minister Lawrence Wong said Singapore was neither pro-America nor pro-China but ‘pro-Singapore’.

Speaking at an event in July 2024, Bilahari Kausikan, Singapore’s former permanent representative to the UN and by far the country’s most outspoken diplomat, made his country’s position even clearer: ‘When we say we don’t want to choose, it doesn’t mean we’re going to stay passive, or try to be neutral, or try to be equidistant. What we mean is that we really want to choose according to our interests in different domains, and there’s no need to neatly line up all our ducks in one direction or another.’

Immigration and migrant workers

Singaporean citizens can make their voices heard on key issues, and immigration policies in particular have proved controversial in the past. In the late 2000s, the government chose to let in large numbers of immigrants to solve labour shortages, but overcrowding, greater inequality and more competition for jobs prompted significant dissatisfaction among the populace.

Singapore still comes under fire for its use of migrant workers, who comprise 38 per cent of the workforce.

A 2020 report by the UN’s International Labour Organization noted that while improvements have been made in key areas such as worker safety, ‘migrant domestic workers are excluded from Singapore’s main labour law, resulting in unregulated working hours. Singapore does not have a minimum wage; women migrant workers are deported if found pregnant; and Singaporean employers often restrict movement of domestic workers, resulting in isolation and restricted ability to seek help when needed.’

It also noted that, ‘significant proportions of the public have negative perceptions of migrant workers’, attitudes that ‘can condone discrimination, exploitation and even violence against migrant workers’.

Kausikan has been particularly outspoken about the need to resist Chinese influence in Singapore, having penned an essay in 2019 titled: ‘China is messing with your mind’. In it, he accused China of trying to influence overseas ethnic Chinese people into accepting allegiance to China as their main identity.

Singapore’s other big challenge comes from the need to keep moving forward if it’s to continue serving as the world’s favourite hub for trade and business. ‘You have to look at the need for Singapore to constantly reinvent itself,’ says Haacke.

‘It’s a global city that has to be relevant if it is to achieve and maintain even higher levels of prosperity. It has to make sure that it has the right sort of investments coming in, and the right levels of technology that it can develop and build upon.’

Lee agrees, arguing that, despite appearances, Singapore is actually an environment that fosters very little home-grown innovation. ‘It’s actually very well known that Singapore suffers from a lack of innovation as a society,’ he says.

‘The majority of ideas come from external places, whether that’s from an outsider or whether from a Singaporean who’s spent many years away and then returned. Personally, I have found that a lot of the more progressive ideas always come from someone who has been away for a fair bit, on almost every single occasion.’

This is the case, he adds, both politically and economically. Pointing to Singapore’s new prime minister, Lawrence Wong, who took over in May 2024, Lee notes that ‘he’s a technocrat in the mould of the leaders of the past. They’ve tried to paint a picture of him as an easygoing guy who loves music and plays the guitar, but Singaporeans don’t know what he stands for. And if you don’t know what he stands for, what his vision for the country is, it’s quite tricky for people to think: “Are we looking ahead, are things going to get better in the future?” It’s the same story for the economy. The approach hasn’t changed at all in the last 50 years.’

Happiness, with a price

So far, Singapore has been remarkably successful in meeting its challenges, even if its model has remained largely static. Often dubbed the happiest country in Asia, it ranked 30th out of 143 countries in the 2024 World Happiness Report – perhaps unsurprising given that during the past two decades, the median wage for Singaporean residents in full-time work rose by 43 per cent in real terms, compared with an eight per cent rise in the USA over the same period.

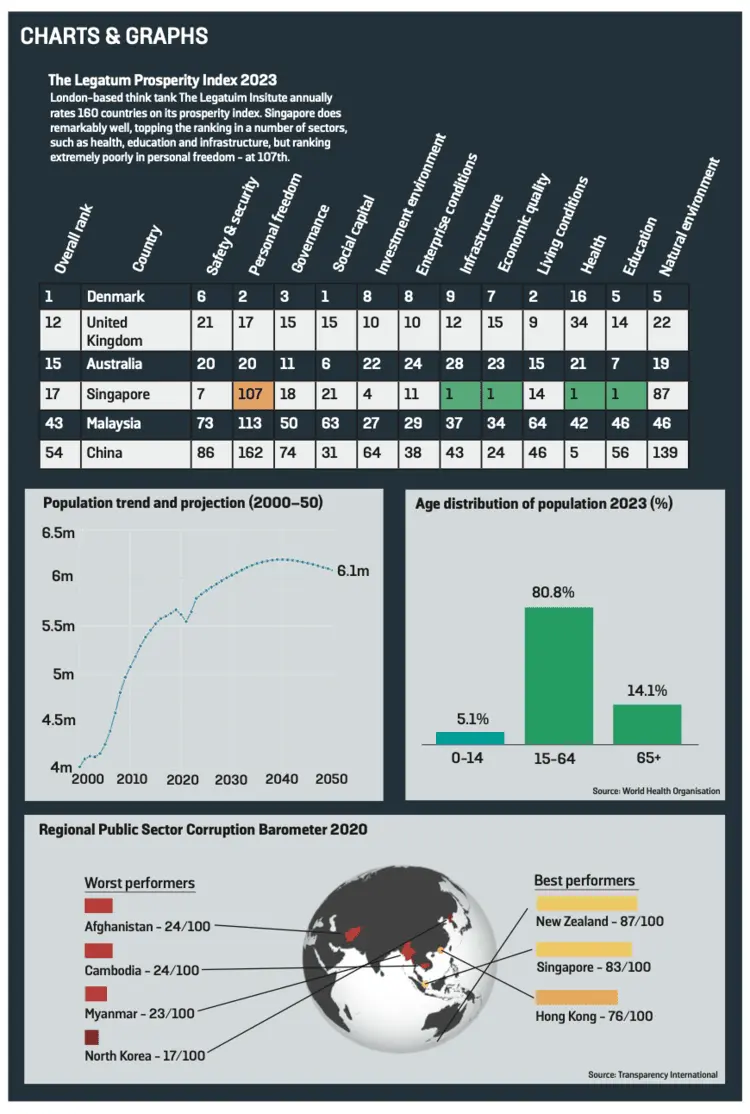

Another global ranking – the Legatum Prosperity Index – compiled by UK-based think tank The Legatum Institute, sums up the country rather neatly. According to the 2023 index, Singapore comes 17th in the world for overall prosperity. Drill down into the details, however, and it seems surprising that it doesn’t come higher, given that it’s ranked first in the world for several of the metrics used, including health, education, access to infrastructure and economic quality.

The reason becomes clear with a second glance: an anomaly on the Singapore row, highlighted orange. The country comes 107th for personal freedoms.

In Singapore, if you don’t let that bother you, it appears a very good life awaits.