More than 700 years since the Black Death pandemic, scientists are developing a bubonic plague jab – but why? And should we be worried?

By

Back in 2020, the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on the world. Entire countries were plunged into lockdowns and millions were impacted in innumerable ways.

Scientists raced to find a vaccine, heralded to help – and it did, protecting those who took it from increased risks of becoming seriously ill from the virus, and helping to halt its overwhelming spread on a global scale.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

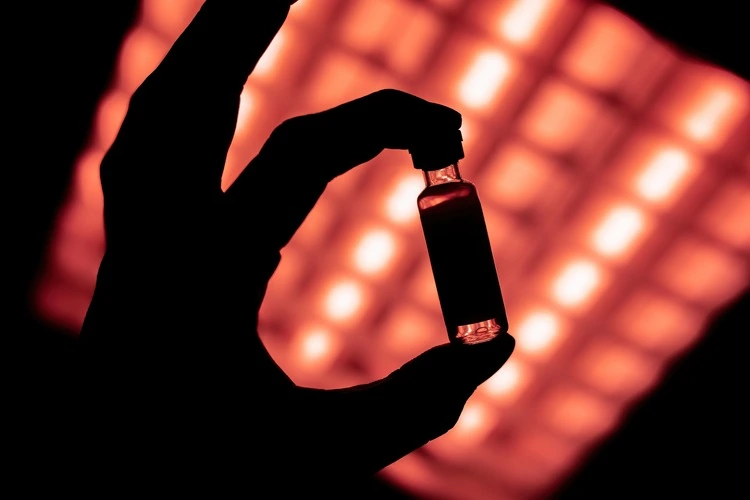

Now, almost half a decade on since a vaccine was created for COVID-19, scientists behind the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab are busy developing another vaccine, this time for a disease whose pandemic last devastated the world more than 700 years ago: the bubonic plague.

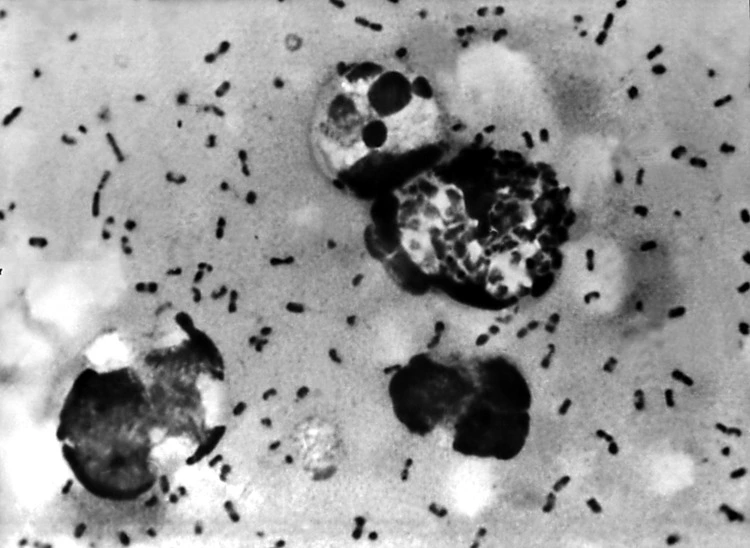

Widely believed to have led to the 14th-century Black Death pandemic (the biggest global pandemic in recorded history), bubonic plague – one of three types of plague – had a mortality rate of between 72 and 100 per cent as it spread across Europe hundreds of years ago.

The scale of the pandemic was almost unfathomable, killing 30 to 50 per cent of the continent’s population: estimates suggest this number could be anywhere between 75 and 200 million people in total. Its symptoms were excruciating: victims would succumb to the disease just a few days after developing the tell-tale fever, followed by a rash and the distinct swellings – known as buboes – in the armpits and groin, which eventually turned black and released pus.

Since 2021, scientists have been trialling a ‘Black Death’ jab on 40 healthy adults – aged between 18 and 55 – with results showing the vaccine’s safety and ability to induce an immune response in people (meaning it can protect them from plague). In early 2025, it is expected these results will be submitted to a journal for peer review.

So why are scientists developing a bubonic plague vaccine now – and should we be worried by the likelihood of a second ‘Black Death’ pandemic?

Antimicrobial resistance

Currently, there is no vaccine in the UK for bubonic plague. UK Government military scientists have recently called for a jab to be approved and manufactured in bulk since plague does have the ‘potential for pandemic spread.’

Despite the last plague pandemic occurring hundreds of years ago, all three types of plague – bubonic, pneumonic and septicaemiac – still exist in parts of the world and infect anywhere between 1,000-2,000 people per year, particularly in rural parts of Africa, Asia and America. In the US, around seven cases of plague occur each year, but deaths are far rarer: 14 deaths from the disease were recorded in the US between 2000-2020.

Cases of the disease in parts of the world such as Madagascar are more common, with a 2017 epidemic in the country leading to 2,119 suspected cases and 171 deaths in just a four-month period.

While antibiotics are the only successful treatment for the disease – if administered early – one of the reasons why scientists are eager to develop a plague vaccine is due to the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance, which may render antibiotics ineffective in treating plague in the future.

In short, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites no longer respond to medicines – including antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, and antiparasitics – used to treat infectious diseases, such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria.

One of the main reasons for AMR is overuse of these medicines in humans, animals and plants, and its effects are stark: it is estimated that bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths globally in 2019.

When AMR occurs, infections become difficult – or in some cases, impossible – to treat, increasing the likelihood of diseases spreading and even death. A plague vaccine could help counter this disastrous scenario if AMR led to ‘superbug’ strains of the disease developing, which could not be treated via traditional antibiotics.

According to the director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, Prof Sir Andrew Pollard – who is also leading the ‘Black Death’ jab trial – the risk of a superbug strain developing due to antimicrobial resistance is ‘very low’, although this likelihood may increase as climate change allows animal diseases, like plague, to spread more easily to humans. For scientists at Porton Down’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, however, there is already a ‘demonstrable’ risk of superbug strains of plague evolving.

Regardless, AMR is a serious concern already across the world, and acknowledging how it may affect the future treatment of plague is vital in avoiding an unmanaged outbreak or second plague pandemic.

Black Death as bioweapon

Another reason to have a stockpile of plague vaccines at the ready is in the event of the bacterium which causes the disease – Yersinia pestis – being used in a biowarfare attack.

‘Malign use in bioterrorism or biowarfare could see the [plague] bacteria spread relatively efficiently,’ explains associate professor of cellular microbiology at the University of Reading Dr Simon Clarke.

It may sound like a far-flung scenario, but it is possible: the bacterium that causes plague can be misused and isolated and grown in large quantities within laboratories. Once dispersed in an aerosol attack, those affected would develop pneumonic plague one to six days after infection – but because of the delay between infection and visible illness and symptoms, people could continue to travel over large areas and potentially infect more individuals.

‘At a time when we’re being warned of increased risk of everything from cyber warfare to a third nuclear age, use of pathogens to destabilise societies and spread panic might be appealing to some bad actors,’ Clarke continued.

Having a plague vaccine on hand would allow for a quick response in the event of a plague biowarfare attack, as thousands could be protected relatively rapidly.

Should we be worried?

Ultimately, scientists are always developing new ways of protecting public health – and vaccines form one of the many strategies in place to ensure the impact of diseases across the world is managed.

Developing a strategy for tackling a plague outbreak in advance of a potential pandemic is an apt example of the saying ‘prevention is better than cure’. While the likelihood of a second Black Death pandemic is slim, scientists are trying to get ahead of the curve to tackling the plague, which more than anything, should be a reassuring thought.