Tensions are mounting in Svalbard, where a Russian mining town is goading the Norwegian authorities

Report by Boštjan Videmšek, Svalbard

We are heading to the Russian-owned town of Barentsburg on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, high in the Arctic Ocean, aboard the expedition ship MS Polar Girl. My Russian guide, Masha, used to live in the run-down coal-mining town of Barentsburg – one of the few settlements in the barren islands that lie midway between the north coast of Norway and the North Pole.

Masha (she asked me not to use her full name or publish her photograph) was born in Omsk in the Urals. Her command of English and Norwegian led her to be offered a job as a tourist guide, and she arrived in Barentsburg in 2021.

‘I jumped at the opportunity,’ Masha explained. ‘Partly because it meant I could help financially support my parents. The first year in Barentsburg was great! I felt much freer… Then everything started to change.’

She left Barentsburg two years ago – not long after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Before the war, Barentsburg was home to some 700 inhabitants. These days, no more than 400 are left.

‘Many people decided to leave. I was one of them,’ Masha told me. She decided to head for Longyearbyen, a Norwegian mining town and the biggest settlement on Svalbard. She quickly found a job on the MS Polar Girl as a guide. She now lives and works on the ship for half the year and travels mainly in Asia for the rest. ‘I love this way of life. I like working with people. Except for those who judge me for my nationality, blaming me for everything that’s happening just because of my passport.’

Besides the geopolitical ructions that are being felt in the region, the dramatic impact of climate change is also starkly apparent in Svalbard. Sixty per cent

of the archipelago is covered with glaciers, and this summer, they’ve been melting at an alarming rate – five times faster than normal, according to the latest NASA satellite data. During my visit, the midday sun had acquired an almost Mediterranean bite. For two days in a row, the thermometer readings exceeded 20°C.

As Masha said with a grimace: ‘This is climate change live.’ The mood was lifted when we spotted a pod of beluga whales no more than a stone’s throw away. All we could do was fall silent.

A SOVIET OUTPOST

The first thing you see as you draw close to the port, owned by Russian state-controlled company Arktikugol Trust, is a vast Communist star carved into the hill looming above the near derelict town with the slogan ‘Миру-мир!’ (‘Peace to the World!’) below.

A few workers were busy loading coal. Dense white smoke was rising from the chimney of a coal-powered power plant. Russian heavy trucks trundled along the gravel road heavily coated with black ash. The now deserted mining company offices were flying both the Russian and Soviet flags.

Under the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, the Arctic archipelago, previously known as Spitsbergen, had become Norwegian. Military use was restricted on the barely inhabited but strategically important scattering of barren islands where the sun doesn’t rise for 84 days each year. However, the treaty allowed all the signatory countries (46 in total) what was termed ‘free pursuit of economic activities’. In effect, this meant the mining of coal. Two Russian communities were established in Pyramiden and Barentsburg, and a Norwegian settlement was developed at Longyearbyen. The only other inhabitants were a few research scientists in isolated outposts. There are no roads connecting the settlements.

‘Before the war, we used to visit each other. We played chess and football’

Torgeir Mork (pictured above), Svalbard meteorologist

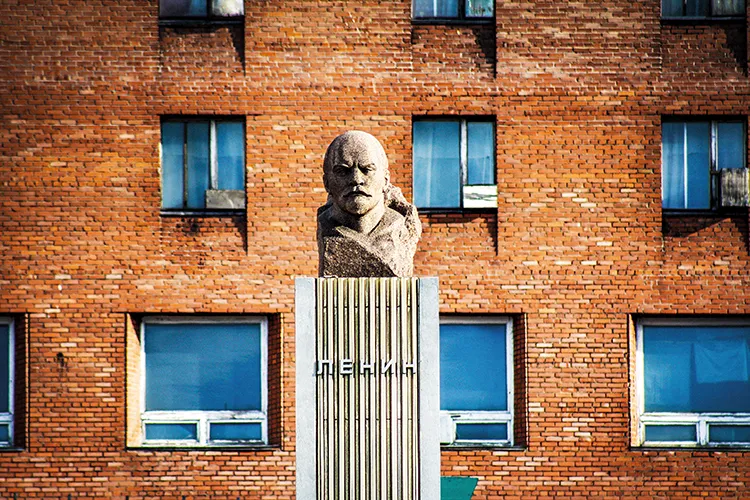

As I climbed the steep wooden steps leading up from the port, stunning vistas of glaciers everywhere around me were sharply contrasted with images from another age. On every step, I could see both Russian and Soviet flags flapping in the breeze. In front of an apartment complex typical of Communist satellite towns, a tall bronze statue of Lenin stared out to sea. The slogan ‘Communism – our goal!’ has been inscribed in huge letters on the apartment building. Remnants of a ‘glorious’ Soviet past were everywhere.

Coal mining was a tough life on Svalbard. The deep mines stretch far out under the surrounding sea. Many of the coal faces were more than a kilometre away and it could take more than an hour to reach them. Accidents were common. Seventy-one people died in the main Norwegian mine between 1945 and 1963. In one incident in 1962, 21 workers died, forcing the resignation of the Norwegian government. In 1996, 141 Russian workers died when a plane crashed as it landed in bad weather. At their peak, the mines employed nearly 4,000 people. Today, they’re mostly depleted. The current population on the islands is now around 2,500, mostly employed in tourism and scientific research work.

However, the Russians are determined to keep their foothold on Svalbard and heavily subsidise the loss-making mine in Barentsburg.

Things are eerily similar in the other Russian mining town in the region, Pyramiden, where coal production stopped in 1998. This summer, a huge Soviet flag appeared on the mountain above the town. Before that, the Russian local authorities erected an Orthodox cross on the town’s outskirts. The Soviet flag atop the neighbouring mountain was planted by Arktikugol’s CEO, Ildar Neverov. Provocative flag-flying seems to have become a Russian Arctic sport. During last year’s victory parade on 9 May, Arktikugol even flew the flag of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic in the centre of Pyramiden. During this year’s parade, Barentsburg’s main street was taken over by a procession of snowmobiles packed with people dressed in Russian army uniforms.

REALPOLITIK

The Russian and Soviet symbols decorating Barentsburg and Pyramiden aren’t to celebrate history. Rather, they represent current Russian realpolitik. The strategic significance of Svalbard is now greater than even during the Cold War. It’s also where climate change meets geopolitics. Warming seas have opened new ocean routes connecting the Far East Pacific region to the Atlantic Ocean. And Svalbard sits right in the heart of these new trade routes.

In the wake of the Russian aggression on Ukraine and the adoption of Western sanctions, the historically fairly sound diplomatic relations between Russia and Norway also took a hit. The Russian Northern Fleet is anchored at the Kola peninsula east of Svalbard, where many nuclear warheads are stationed. At the same time, NATO is putting mounting pressure on Norway to bolster its military presence in the Arctic. A year ago, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs re-categorised Norway from an ‘unfriendly’ to a ‘very unfriendly’ country.

In 2019, Vladimir Putin created a special ‘Svalbard committee’. In past speeches, the Russian leader often pointed out the strategic importance of the Arctic and its natural bounties for Russia’s economic growth. In 2007, Russia opted to fly its flag on the seabed at the North Pole.

Some of the other signatory countries of the Svalbard Treaty have also revealed increasing interest in Svalbard. China now openly desires to rebrand itself as an ‘Arctic country’. In July, the Norwegian government stopped the sale of the last great chunk of private property on Svalbard to an unknown Chinese buyer. In China’s view, halting the sale represented a breach of the Svalbard treaty.

Russia also intends to open a new centre for scientific research at the abandoned town of Pyramiden. Moscow has already officially invited China, India and South Africa to participate – as well as Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Russia announced its plans for the opening of the scientific centre right after Norway declared that the UNIS University Centre in Longyearbyen was the only institution allowed to provide higher education in the archipelago. Norway sees the introduction of the new scientific centre as another territorial move.

LOCAL VOICES

At the time of my visit this summer, Barentsburg seemed quiet and almost empty. Only a few people could be seen strolling its main street, most of them tourists. The small, beautiful wooden Orthodox chapel built to commemorate those killed in the 1996 plane crash also looked deserted.

Four and a half years of continuous shutdown – first Covid19-induced, then war-related – had taken a heavy toll on the Russian mining town, where the quality of life used to surpass that of the Norwegian Longyearbyen, located on the other side of the fjord.

Anthropologist Dina Brode-Roger (pictured above)

The Russian administration is not interested in

communicating with Europe. It was different during the cold war

The French/American anthropologist Dina Brode Roger has been regularly returning to Svalbard since 2016. On average, she spends six months each year on the Arctic archipelago. Over the past eight years, she noticed tremendous change sweep over Svalbard. Both climate change and mounting geopolitical tensions have had a huge impact. Since the invasion of Ukraine, she has stopped visiting Barentsburg. ‘It was a personal decision,’ she explained. ‘There used to be good contacts between the Norwegian and the Russian side, especially through cultural and sporting exchanges. There was a lot of cooperation and mutual assistance. People needed each other back then, when miners lived and worked on both sides. Now, things are very different. Especially on account of the invasion of Ukraine and the things that are going on in Russia.’

She added: ‘A lot of people have come to Longyearbyen from Barentsburg over the past two years. Their experience helped shape the views of Longyearbyen residents on what was going on in Barentsburg. The current Barentsburg authorities are much closer to Moscow than ever. The Russian administration is not interested in communicating with Europe.

Some other Geographical stories you might be interested in

‘Russia is skilled at recognising the weak points of different countries, especially the neighbouring ones. The Russians know very well which buttons to push. Norway is placing a great emphasis on its presence in the Arctic. Russia knows this, so it keeps sending clear signals through its actions in Barentsburg. They clearly wish Norway to respond to these provocations.’

One of those still trying to maintain at least indirect relations with his Russian colleagues is Torgeir Mork, the main meteorologist at the Longyearbyen airport for the past 20 years.

Mork deplores the fact that all contact with Arctic-based Russian scientists had been cut off since the start of the war. ‘Every morning, I still send my readings and predictions to Barentsburg – just like I always did,’ he told me at his post at the airstrip. ‘I never get a reply.’ The long-serving meteorologist is convinced that to gain understanding of the changes sweeping the Arctic region, international cooperation should be paramount. ‘Before the war, we used to visit each other. We played chess and football. I can only hope this wretched war is over as soon as possible.’

Russian writer Dina Gusein-Zade, 36, came to Barentsburg after the end of the coronavirus lockdowns, looking for peace and quiet to write. Her command of foreign languages got her a job as a tourist guide. She told me: ‘Human beings should not be forcefully separated! All of us living in the Arctic should be cooperating. We need each other. I can only hope that the rough times end soon.’

She added: ‘It is not fair that ordinary people must pay the price of political decisions. It is unfair for us to be treated as criminals and enemies solely based on our nationality. No country and no nation are intrinsically evil!’ Now, Gusein-Zade, like many people of her generation, is planning to move to Turkey. I asked her how the sanctions have impacted personal relations in Barentsburg. ‘They have had a huge impact!’ she said. ‘Lots of people have departed. Those of us that remain like to help each other. This is one of the advantages of living in a small community.

‘But the effects of the sanctions have strengthened existing conflicts within the community. The people are angry. One can now really observe people harden in real time. There’s also a lot of fear coming from both sides. Cutting yourself off is not a solution. Isolation often spells catastrophe. Especially here, where we are already more or less cut off from the world. We need to stay connected.’

Kari Aga Myklebost, a professor of history at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø, later told me: ‘The major changes in Barentsburg and within the Russian community on Svalbard began in 2021. It was then that the new Russian consul in Barentsburg and the new Arktikugol CEO began taking on greater powers. Arktikugol was turned into a vehicle for Russian foreign-policy goals. Powerful Russian politicians were involved. Since then, Moscow’s influence only intensified. After the aggression towards Ukraine, freedom of expression took a further hit. The developments in Barentsburg are a reflection of the repression currently taking place all over Russia.’

She added: ‘The new regime immediately began harping on about the rights of Russian workers in the Arctic and on Svalbard. And also about the historical rights and the protection of the Russian population.’

Aga Myklebost described the recent changes as the ‘Putinisation’ of the traditionally moderate Barentsburg.

‘Very similar messages began to be issued from the higher reaches of Russian politics,’ she went on. ‘It is a well-known tactic. The Kremlin keeps repeating that the West seeks conflict with Russia. The same language was used before the invasion of Ukraine. Russia sees this sort of propaganda stunt as cheap, simple and effective.

‘The Russian motives on Svalbard have not changed. They want to keep control of the Barents Sea, which is now being opened for international trade due to the melting ice. This is why Russia keeps trying to contest the Svalbard Treaty and Norway’s sovereignty over the archipelago. They want to prevent Svalbard from being controlled by NATO. If there is ever a serious conflict between Russia and NATO, Russia will be forced to close off the waterways around Svalbard as they lead directly to Russia and the Kola peninsula, where a great deal of Russian nuclear capability is stored.’

For climate scientists, these rising tensions could not come at a worse time. Kim Holmén, the former director of the Norwegian Polar Institute and now its special advisor, told me: ‘Let’s hope that the current poor relations in the Arctic are not the new normal. The future of Arctic research is at stake, given that roughly half of the Arctic coast is located in Russia.

The Russian motives on Svalbard have not changed. They want to keep control of the Barents Sea

History professor Kari Aga Myklebost (pictured above)

’In order to further our understanding, we need data – we need collaboration.’

Holmén, considered to be one of the foremost authorities on Arctic research, believes that the current halting of the information flow can be attributed exclusively to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. ‘Before that, the Polar Institute had an excellent collaborative relationship with Russian scientists. Norway no longer allows such contact between institutions.’

He told me he had many friends among Russian scientists, but conferring with them was no longer possible. ‘Human knowledge is required to understand how the Arctic functions. We need reports from the field. What is going on with the permafrost? What’s happening to the fish, to the oceans, to the glaciers? Science has been dealt a huge blow.’