New research reveals the growing problem of modern slavery in the UK and the ways in which victims are criminalised

For years, anecdotal evidence has suggested that the UK’s prison system is failing victims of modern slavery, many of whom may be imprisoned for crimes they were forced to commit. ‘I’ve probably [seen over] a hundred over the last few years and it’s increasing exponentially,’ one forensic psychologist in the UK prison service told human rights researchers. ‘So many victims are not being identified as victims. They’re serving criminal sentences and being treated as criminals, as offenders.’

According to official government statistics, published last year, the number of potential victims of modern slavery in the UK has reached a record high. In 2022, 7,936 referrals were made through the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) – the process used to identify and support potential victims – a 10 per cent increase on the previous year. The National Crime Agency (NCA) states that while victims are recruited into many sectors, from construction to agriculture to the care industry, criminal exploitation is the most commonly reported.

The majority of criminal exploitation cases involve drug offences; victims are forced to work as drug dealers or to tend to cannabis farms. Cannabis is the single biggest drug market in the UK (an estimated 2.6 million people consumed 240 tonnes of it in 2022) and experts say that domestic cultivation is a key driver of criminal exploitation and modern slavery in the country, with UK, Vietnamese and Albanian nationals the most commonly identified victim groups. Yet in 2020, researchers at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology reported that police forces were failing to identify modern slavery victims during cannabis farm raids due to insufficient training and officers’ preconceptions.

There are no official statistics on the number of modern slavery victims in UK prisons, says Marija Jovanovic, a human rights lawyer and senior lecturer at Essex Law School. ‘Nobody knows how many are serving sentences, where they are, or why they are in prison.’ Interview statements that she and her colleagues have gathered from prison staff, experts and modern slavery survivors, however, suggest that the scale of the problem is likely to be much larger than previously estimated. Given how few convictions there are on modern slavery charges, Jovanovic says, it’s not out of the question that there might be more survivors in UK prisons than perpetrators.

Prisons represent a blind spot in the UK’s response to modern slavery. Currently, only designated ‘first responder organisations’ are able to refer suspected cases of modern slavery to the NRM. These organisations include the Home Office, police and a number of charities that support victims of modern slavery – but not prisons.

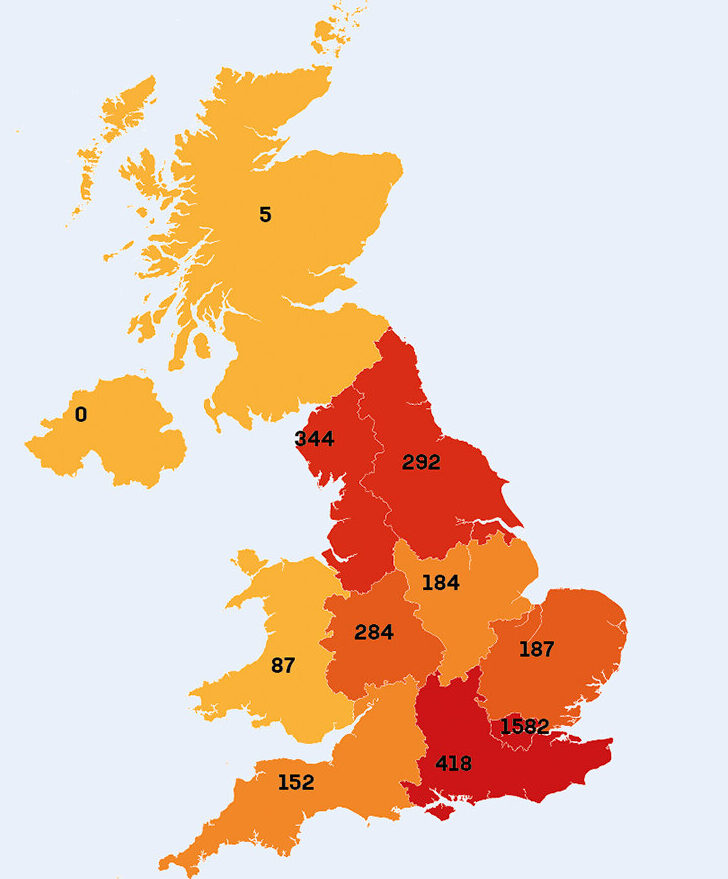

July 2022-June 2023

‘I don’t think it was a conscious decision to omit them,’ says Jovanovic, ‘prisons have just never really featured in the discussion.’ In fact, it was only in 2022 that prison staff were first issued with guidance on how to identify and support victims of modern slavery, the result of a legal challenge brought by the Anti Trafficking and Labour Exploitation Unit, a charity that provides legal representation to victims of modern slavery and human trafficking. Around the same time, HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) made the recommendation that every police force in England and Wales appoint a single point of contact (known as Modern Slavery Single Points of Contact, or SPOCs) to improve prison staff’s ability to identify and support survivors.

There are a number of reasons why it may be difficult to identify someone as being a victim of modern slavery. People who are in prison may have already lost any trust they had in authorities and be unwilling to cooperate. Some may have been threatened by or even placed in the same prison cells as their traffickers. ‘Prisons are in a bad position because they don’t control who comes in,’ says Jovanovic, ‘they are the last stop on that journey. Nonetheless, it’s very important that victims are identified and supported because, if they’re not, the cycle of exploitation continues. We have heard of instances where people released from prison are being collected by traffickers and exploiters.’

So far, the introduction of SPOCs has done little to improve victim identification in UK prisons. A lack of adequate training, resources and general awareness of the issue are the biggest barriers, says Jovanovic. ‘These aren’t newly hired roles. They are existing prison officers who now have an extra duty on top of their existing work, which is a challenge because prisons are under-resourced, and there is a huge turnover of staff.’ Despite this, Jovanovic says that HMPPS, with whom she has been working closely, has acknowledged that there are many problems left to solve. ‘Even though there’s so much more to be done,’ she adds, ‘the reality is that in other European countries we haven’t seen evidence of any guidance for prisons. England and Wales are pioneers in that regard.’