Laura Coffey went on a quest to find the real-life islands that inspired the wanderings of Homer’s epic hero, Odysseus

I always have to turn maps around to figure out where I am, much to the disdain of my sister-in-law, who studied geography at Oxford. The correlation between what a map shows and what I see in the physical world is something my brain puzzles with. I’m often lost, taking wrong turns in every sense. I can never seem to remember the official names of things, I’m never quite sure where north is and fail spatial awareness tests. The bend in the green river I love most doesn’t seem to me anything like the way it’s drawn on the map. The way I navigate is by landscape and memory, the remembrance of the twist of a certain road, the shape a fallen tree has made, the things I saw and did, the people I loved.

I’m happy to follow a friend through a strange city, reliant as a child, too busy talking to remember anything about the route we took. But I could list all the addresses I’ve stayed in when I visit New York City, tell you coordinates about the kind of girl I was at each of those places and how she’s changed. I could give you a map of me inside cities. If you wanted it, I could draw my version of London for you – the pavements I’ve bled on, the bridges I’ve cried on, the cobbles on South Molton Street where I was kissed so deeply I fell in love, the flower gardens in Hyde Park where I broke up with him a year later, the street behind the Strand where I was knocked off my bike and fell in the snow and a Jesuit priest held my hands and blessed me as my knees bled, and the snow kept falling, and the bike wouldn’t work.

Before there were accurate maps, there were cartographers who attempted to draw the limits of the known world. And there were also myths that told it into being. Making a map is not just a case of technology and technique, of mathematics and spinning compasses, it’s equally about aesthetics – designing and drawing an illustration of the world, folding it down into two dimensions. It’s both a precise and an imaginative act. Reading a map, in turn, is also an imaginative act. The mapmaker imagines how best to draw reality, and then we must also imagine and connect things together, to interpret it: overlaying the world of the map onto what we see in front of us. I like to draw on maps, mark where I’ve been, sketch out my hiking routes in pen after I’ve completed them, draw in black the path I took to get to the mountain.

At the edges of their maps, where the cartographers had no more information, story took over, carving terrible monsters in strange lands, making sea creatures into mermaids, foretelling of danger and doom, of valour and courage. Stories tell us the contours of the world in more dimensions and more colours than Ordnance Survey could ever capture. Myths create meaning, show us how to find our way when we’re lost and alone and not feeling in the least bit brave. They give us heroines and allies and perils and the ever-burnished hope of redemption, of finding our way home again, and being welcomed back, at long last.

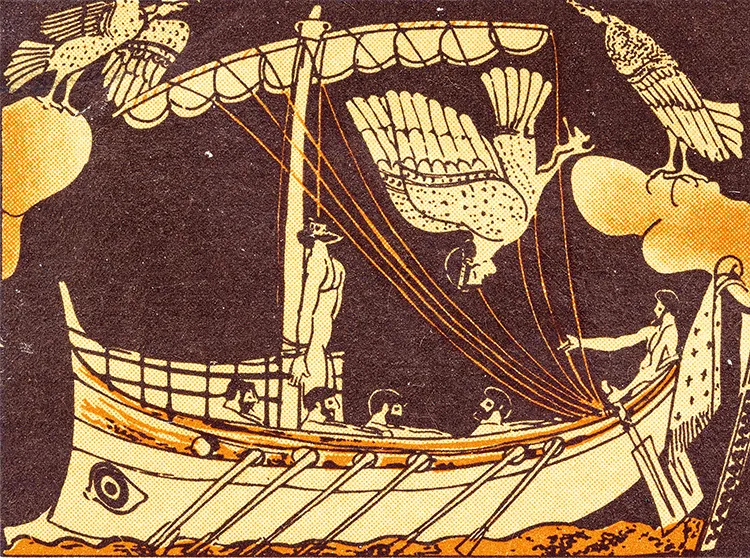

Myths are also our earliest, oldest geography lessons, explaining the shape of the world. Storms and tempests and exploding volcanos are the unpredictable wrath of gods. Way before meteorologists poured sunshine into mathematical equations, in order to forecast the weather, the Greeks invented Helius. Whether he would shine tomorrow was immeasurable, dependent on his mood as he gunned his fire-chariot across the sky. When ships were lost at sea, someone had forgotten to venerate Poseidon, and even if they had made a sacrifice to him, deaths at sea could still be explained since the god of the ocean, like all the rest, held grudges, was petty.

Myths can also be mapped – the link between imaginary and real places has obsessed people over the centuries seeking to understand where The Odyssey was set, where Ithaca was located, pondering which islands best correlate to the descriptions of the fantastical lands given in the story. British American classicist Emily Wilson’s view is pragmatic – she says: ‘There is some correspondence between the world of Homer and the real world, although the relationship is partial and inexact.’

Partial and inexact have not deterred generations of scholars from putting competing theories forward, often based on nothing much more than speculation and whimsy.

It started with ancient scholars such as Strabo, the godfather of geography. Then in the 19th century, due to the revival of classical studies and the surge in travel and exploration, there was an explosion of interest in trying to figure out where precisely the mythical lands of The Odyssey were, in real-world geography. Scholars pored over descriptions in the story, the placement of a cave, the arrangement of the stars, and how geological forms were rendered in the poem to try and figure out the correspondence to actual islands. There’s no consensus and the theories diverge and morph. Some are hyper-specific, for example, that the Strait of Messina, with its tricky currents, is exactly where Odysseus got trapped between the whirlpool and the sea monster, while others talk more broadly – about the coastline of southern Italy being an inspiration for the fantastical lands, rather than an exact rendering.

Enjoying this article? Why not check out some related reads…

Something about this attempt to map the imaginary onto concrete-literal geography, its futile nature perhaps, caught my attention and held it. If myths function to help us make meaning of the world, maps help us find our footing, understand where we are in gravitational space.

I pictured those 19th-century men, smoking their pipes, stabbing their fingers at passages in the poem, arguing with each other, earnestly defending their theories. The gap between all their different maps was what fascinated me most, it opened up space for multiple interpretations.

I needed a different map, a way to access the mythical, to believe in the gods again. I found myself caught up in the romance of searching for imaginary islands in the real world. It became a quest that became an obsession that became a book, Enchanted Islands, for which I visited the following islands which might have inspired Homer and could certainly inspire your next holiday!

Marettimo, Egadi archipelago, Sicily

Samuel Butler, a Victorian novelist, believed Ithaca wasn’t in Greece, and that Homer had been misgendered. The Odyssey, he contended, was quite clearly the work of a ‘brilliant, high spirited woman’ and that when this ‘poetess’ wrote about Ithaca, Odysseus’s home, she was picturing the island of Marettimo. While the theory sounds, on the face of it, progressive, it’s actually fairly insulting, because Butler attributes the clunky elements of the poem to the fact that it was written by a girl. Marettimo, which means ‘sea thyme’, is the westernmost of the Egadi islands, 45 kilometres off the western coast of Sicily. There’s something piratical, rugged and remote about this place – it’s famous for hiking, botany and birdwatching.

Goat island – Favignana

The sister island to Marettimo in the Egadi archipelago, Favignana at the time of the Ancient Greeks was known as goat island, or in Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey, the ‘island full of wonders’. Cala Rossa, the most famous beach here, is supposed to have been the site of decisive naval battle between Rome and Carthage – the sea turned red with the blood of the vanquished Phoenicians, giving the cove it’s name.

The island of the Sun God: Sicily

According to some theories, Sicily is the land of the sun god, Helius. The quality of the sunlight here is supposedly scientifically distinctive: something about the combination of low levels of water vapour, the location of the island and its atmospheric clarity means the light is less diffuse here – in other words, it blazes.

The floating island of Aeolus: Stromboli, Aeolian archipelago

The ancient Greek geographer Strabo wrote, ‘It is here they say that Æolus resided’, and perhaps he was right. There is something godlike about this wild island located about 60 kilometres off Sicily’s north coast. It has one of the world’s most active volcanoes – hike up in the late afternoon and watch the sun set as you climb, the light falls and stars sparkle across the night sky as fire shoots up into the darkness. It really feels magical here.

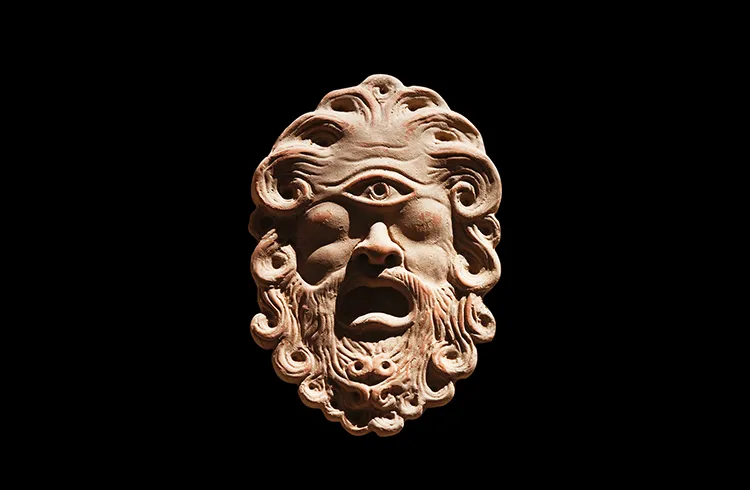

Island of the Cyclops, Menorca

Mauricio Obregón believed the island of the one-eyed Cyclops could be one of the Balearic Islands. Unlike its frenetic, partying cousins, Menorca is relaxed, family friendly, and alongside its famous beaches, boasts some extraordinary Bronze Age archaeology that’s associated with legends about giants.