Kristina Chan’s solo exhibition, ‘Habitable Climes’, is a thought-provoking exploration of our relationship with maps, landscapes, and the ever-changing world around us

According to photographer and printmaker Kristina Chan, you can see how our geographical understanding of the world has evolved by looking at historical maps – such as the engraved world maps by Forlani and Berlinghieri, held by The Sunderland Collection. ‘The engraver’s confidence is visible in the line work: in the fluidity of his curves and corners, and in the depth of his lines, which reveal a quick and steady hand, or whether he was working more slowly,’ says Chan. ‘You can see where the errors have been physically scratched out.’

Chan’s fascination with the process of mapmaking, coupled with her expertise in printmaking, first sparked her interest in The Sunderland Collection, a private archive of rare antique maps and other historical artifacts. ‘It became really fascinating to look at maps I was less familiar with, all the different variations of Ptolemaic maps, for example,’ Chan explains. ‘And by spending a good amount of time looking through the archive, I started to see how different ideas evolved, how each country and culture had a different take on mapmaking and geography.’

The result is Chan’s compelling new exhibition, called Habitable Climes, which explores ideas about remote territories and changing, less-documented geographies, and which runs from 12 March to 30 April at Canada House, London.

‘I became really fascinated with the idea of habitable climes, which the exhibition is named after,’ says Chan. ‘I liked looking at the evolution between this quite linear idea of the world, and how that became what we see today as latitudes.’ Her new work centres on the exploration of two remote landscapes, the Arctic Circle and the Nevada desert, and highlights the stark contrast between these two environments, both physically and perceptually.

‘What fascinated me about the Arctic Circle, for instance, was this idea of its “unchartedness”,’ Chan recalls, referencing the blank, unexplored areas on early Barents’ maps of Svalbard. ‘There’s such human effort in the trial and error of mapmaking, in drawing what we now see as a simple line, and seeing how those lines evolve.’ One day, in the ship’s wheelhouse, she noticed a school binder filled with hand-drawn maps alongside the ship’s modern GPS systems. ‘The captain would flip through them, showing us how, just the night before, we were supposedly anchored to an island that didn’t exist,’ Chan explains. These maps, she learned, were often created for funding, to “prove” 19th-century discoveries. ‘It was a fascinating collision of technology, knowledge, climate, geography, and politics, all unfolding in a single moment.’

In contrast, her experience in the Nevada desert revealed a profound sense of emptiness. ‘I was trying to find the exact opposite of the Arctic in terms of visuals, perception, assumption,’ Chan says. ‘We often think of the Arctic as this empty space, but it’s so alive. There were reindeer, polar bears, seals and walruses. You’d go off with the guide, and they’d be able to spot a tiny patch of these unbelievably small wild flowers, and you’d learn that these flower only grow on bone marrow, so there must be a whale bone hidden beneath the snow.’ Standing on the bottom of a dry lake bed in Nevada, just a short distance from the largest Alpine lake in North America (Lake Tahoe), was a very different experience. ‘I’ve never felt a place so empty and so devoid of life.’

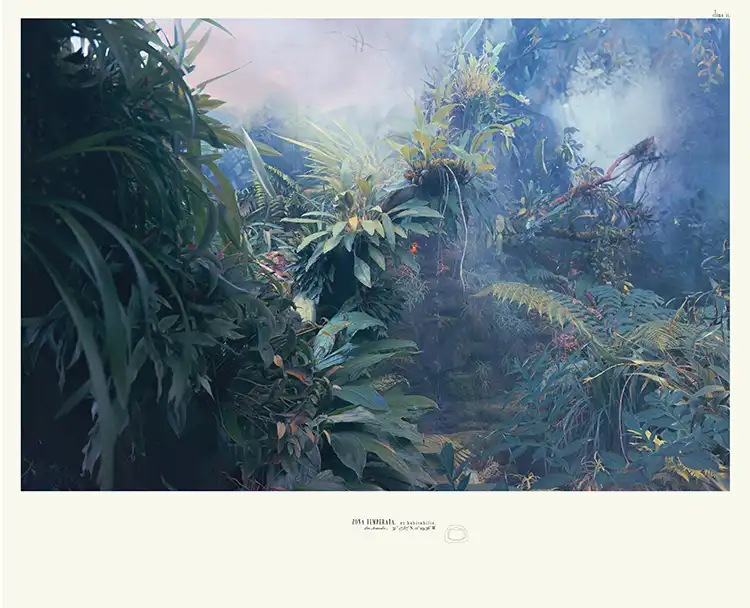

Large-scale prints, born from Chan’s explorations and her studies of the maps in The Sunderland Collection’s maps, form the core of the new exhibition. Chan explains that her artistic process involves meticulous observation and documentation, combining photography, sketching, and collaboration with local experts. ‘I do take photos in situ, and I sketch, and I reflect, I learn,’ she says. ‘But once I’m back in the studio, I focus on my primary feeling, such as the Arctic-desert juxtaposition, and then I’ll look back over the images with that in mind, and figure out what I want to express with them.’

Chan’s fascination with the very process of mapmaking, which lead to a collaboration with the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), also resulted in Impossible Measures, a series of 16 etchings that form part of Habitable Climes. I knew the print process,’ she explains, ‘but I became intrigued by the scales, measurements, and technology involved.’ Photographing historical instruments from the RGS-IBG collection, such as sextants once used by Darwin and Livingstone, behind frosted glass created an abstract effect, suggesting their accuracy and significance have become obscured through time.

Habitable Climes also prompts us to contemplate the future of liveable spaces, especially in the face of climate change. ‘I do hope that when people see the exhibition, they see it see is as a journey, or perhaps a time lapse,’ Chan says. ‘I’m interested in the idea of habitable climes from a historical perspective, but I also want to question our present-day expectations of the places we think of as being habitable.’ She points her images inspired by a drought-stricken Australia: ‘It looks less like a home and more like an 80s sci-fi vision of Mars.’

For those unable to visit the exhibition in person, a parallel online exhibition will also launch on 12 March 2025 on The Sunderland Collection’s website, Oculi-Mundi.com, that offers a deeper dive into Chan’s artistic process and the historical materials that inspired her work.

Habitable Climes will run from 12 March to 30 April 2025 at Canada House, Trafalgar Square, London SW1Y 5BJ.

The Sunderland Collection is a private collection of rare antique cartography. This exhibition of new works by Kristina Chan is the culmination of the second edition of the collection’s acclaimed Art Programme, which launched in 2024, and is curated by contemporary art expert Beth Greenacre.