Alec Ash, in this extract from The Mountains Are High, explains why he and many others are opting out of the rat race of modern China

Sometimes, something has to change. The heart baulks. The tension snaps. The urge strikes to begin anew, an itch that grows until we can bear it no more. Or change is thrust upon us, unbidden — a new job, a new relationship, a windfall, an accident, a divorce. Most difficult of all is inner change. Yet the challenge of transformation is a measure of how deeply we long for it. What we need most is that which we dread to begin.

Born, bred and educated in mossy Oxford, England, the first decades of my life had been quiet, privileged, sheltered — the proverbial frog in the well who thinks the circle above him is the whole sky. On graduating, in 2008 I studied Mandarin at Peking University for two years, thrust into a foreign culture and an urban pace that were unfamiliar. My ceiling had burst open; the frog was out of the well. After a stint in London, in 2012 I returned to Beijing as a writer and editor, and didn’t look back for another seven years.

Foreigners in a foreign land, we guzzled at the firehose of China at the peak of its growth and ambitions. The cultural novelty and chaotic news cycle alone were enough daily stimulation for a lifetime. The sheer size and pace of Beijing was thrilling, galvanising. The protean beast of China charged forward, and we were fleas clinging to its back, along for the ride.

Those teenage years of the 21st century were a debutante time for China on the world stage – as for me in my 20s – when anything seemed possible. After the economic opening-up of the 1980s and 1990s, in the 2000s and early 2010s, the country felt it was tentatively liberalising, inch by inch, with an active civil society that seemed on the brink of changing the nation’s sclerotic politics. The capital attracted artists, rockers, free-thinkers and thrill-seekers from all four winds. Others were busy getting rich, sucking at the marrow of the world’s most vibrant economy.

By 2017, something had changed. Xi Jinping was in his second term and flexing his muscles as a strongman. Then he removed term limits from his office entirely. China was tightening rather than opening. Economic growth was slowing. The first reports of internment camps in Xinjiang were surfacing. Human rights lawyers and feminist groups were arrested. Relations with the West soured. Journalists were booted out of the country. The artists and activists fled ship. Income inequality and unemployment were rising. Beijing no longer felt like the hub of a dynamic nation, but the nexus of a police state.

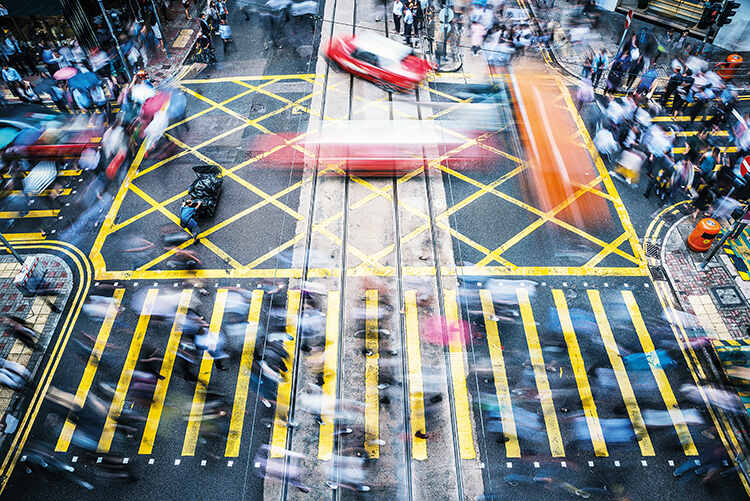

Cities are hard, unforgiving things, but there has always been something unliveable about Chinese cities in particular. Soviet super-blocks crammed with concrete high-rises. Roads blocked by fencing down the middle to prevent jaywalkers. The miasma of traffic fumes and smog that suffuses the air. The problem is not Communist control so much as capitalist excess, the familiar litany of urbanisation and its discontents. Long commutes. Honking cars. Nameless neighbours. Cramped apartments. Ballooning prices. Bad air. The toxins of city life that accumulate in the liver of the soul.

Old friends left Beijing, in the great churn of expat life. My long-term relationship was having problems that I chose to ignore. Without a new project after my first book was published, I was feeling listless about work. Put simply, I was in a rut. I wasn’t yet ready to leave China, but I needed a retreat. Somewhere to wait out the winter, until spring came again.

Rap-tap-tap. I remember the knock on my door, the literal wake-up call. A local official, informing me in neutral tones that the building I lived in was an illegal structure and due to be demolished. If you had asked me if I wanted to go, I would have said no. I needed the push to realise it – I was ready for a new horizon. Something had to change.

I first fantasised about moving to Dali while scrolling through my friends’ posts on the messaging and photo-sharing app WeChat. I lingered on a post from Zhazha (literally ‘Boom Boom’), an ebullient, 30-something Chinese photographer I hadn’t seen in a while. It turned out he had also felt burnt out by Beijing and had moved to a rural village in a far-flung corner of the nation.

Flipping through images of his new digs, I wished I had too. His farmhouse had a cobbled yard: grass poking between the cracks, foliage-fringed, with a Taoist yin-yang formed from pebbles at its centre, next to a persimmon tree and a reading bench. The house itself had old wooden beams, and a skylight boasting a view of the three ancient pagodas Dali was famous for, with towering mountains as their backdrop.

From my city apartment, it looked like heaven – space to think and breathe, away from the smog and the honk and the hurry. Zhazha bought vegetables from his village market, grown in fields nearby; he spent long, lazy days hiking up to hidden waterfalls in the hillside; he focused on creative projects, without having to worry about rent or living costs. Later, I asked him why he had left Beijing.

‘Beijing used to be fun,’ he said, ‘but it’s difficult to live in and to earn enough money, so I didn’t like it. I discovered actually I wasn’t happy. So I migrated to Dali in order to find a new way of life.’

Finding a new way of life was a quest I began to hear a lot. Perhaps because I sought it myself, I started to notice how many around me did too. In China, city malaise was writ large by the nation’s sheer scale and pace of urbanisation. They talked of it as ‘city sickness’. In the space of 40 years since the 1980s, China had squeezed in the industrialisation and economic growth that Western countries had taken centuries to achieve. But now its citizens were stepping back to ask: what was it all for? I’m richer, but am I happy?

A new buzzword was starting to appear online: ‘involution’. The Chinese, neijuan, literally means to be ‘rolled up inside’. If you worked 12 hours a day, then you were ‘rolled up’ by over-work culture. If you were a student with back-to-back extracurricular and exam-prep classes, then you were ‘rolled up’ by the education system. If you were commuting for two hours to pay off a shoebox apartment and buy a car so you could attract a wife, you were ‘rolled up’ by social conventions. But bloodsucking capitalism had begun to clot. It was the rat race, the hamster wheel, and the rodents were revolting.

A solution was proposed: instead of standing or sitting, lie down. The word used for this, tangping, literally meant to ‘lie flat’ but signalled a deeper opting out of the system. If the game was rigged and social mobility impossible, why even bother? Quit the rat race; sleep in instead of working late; break the cycle. The most extreme form was to escape the city altogether – that hub we had gravitated towards in search of opportunity, only to be disenchanted. That was what Zhazha had done, fleeing to country climes. The rural environment of Dali in southwest China was already jokingly dubbed the ‘capital of lying flat’. Others called it ‘Dalifornia’, for its good weather and chill vibes.

This back-to-the-land trend was a direct reversal of everything upwardly mobile Chinese people used to hold dear. For decades, those born in the countryside had wanted only to escape its poverty. Now, since 2011, more people lived in urban than rural areas. Yet for the generations born in China’s mega-cities, some wanted to get out – to return to the soil where their forefathers had come from. Instead of chasing bright lights in the big city, they dreamt of open farmland and the quiet life. After 40 years of urbanisation, the flow was reversing.

It was still a minority who were privileged, or crazy, enough to quit their city jobs. Some were the enriched middle class, seeking a patch of sun to lie in, equivalent to a Londoner’s cottage in Tuscany or a lake-house in upstate New York. Others were penniless urban workers who wanted to drop off the grid and reinvent themselves entirely. Either way, this inverse migration from city to country, once a trickle, was becoming a stream. Zhazha was an avatar for the trend: a 30-something creative professional fed up with the city, who wanted to live his own life instead of someone else’s expectations of what that should be.

‘My parents’ generation worked hard all of their lives to leave the countryside and move to a township so I could have better opportunities,’ he told me. ‘They didn’t understand why I would go back to the countryside.’

It had taken just two generations for a Chinese family to pass from pre-industrial agrarianism to post-material urban malaise – for the grandchild of farmers to return to the land.

‘I just think there’s more to life than what everyone expects you to do,’ Zhazha said. ‘To have a job and a car and a house and earn lots of money.’

His unease was a refraction of China’s story at large, where worshipping at the font of economic development had left a spiritual vacuum at the nation’s heart. What now? What next? Am I happy?

The mountain valley of Dali that he chose for his escape seemed the epitome of that new life. Antithesis of involution. Capital of lying flat. Dalifornia. Tucked away in the highlands of Yunnan province, southwest China, Dali sits in a fold of the Hengduan mountain range, which rises westward to become the Himalaya. At an elevation of 2,000 metres, the terrain keeps climbing until the border of Tibet, 300 kilometres northwest. Myanmar is half that distance away and Laos a little further to the southeast. Until a century ago, this was at the heart of what scholars term Zomia, the ungovernable mountainous zone between nations. It is a good place to hide in.

Over the last few decades, Dali has attracted a new kind of outsider. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was a rare traveller who stumbled into the valley. Back then, the Old Town and surrounding villages were undeveloped, with dirt tracks, farmland and crumbling houses.

The same mountains that made Dali picturesque kept it poor, obstructing the modernisation that came first to China’s eastern seaboard. Yet this was what the travellers were looking for: a rustic escape from explosive urbanisation, and a refuge from the politics of the cities – including for dissidents who fled here after the Tiananmen crackdown, such as the poet Liao Yiwu, who lived there in the early 2000s.

By the new millennium, Dali had also become a go-to destination for the in-the-know backpacker, a northern extension of the banana-pancake trail through Southeast Asia. Part of the appeal was that marijuana grew wild in Dali’s hills (and still does). It was an easy place to get high, in both senses of the word. In those days, local Bai grannies would sit along the main strip of the Old Town – dubbed ‘Foreigner Street’ for all the Western backpackers – and hawk their self-picked wares to passing foreigners in broken English: ‘Ganja, ganja?’ This continued until local police cottoned on that the plant had uses besides twining into rope and chewing its seeds, and told the grannies to stop pushing.

In 2014, Chinese folk singer Hao Yun penned a hit song that captured the zeitgeist: ‘Go to Dali’. ‘Are you unhappy in life?’ went the lyrics. ‘Haven’t laughed for a long time and don’t know why? Go to Dali! Go to Dali! If you’re not happy and you don’t like it here, why not head west, all the way to Dali?’

These city arrivals in the countryside were dubbed fanxiang qingnian, or ‘returning youth’, although every generation was represented. Some called themselves xinyimin – the ‘new migrants’. Others used a simpler term: ‘new Dali people’.

I had already visited Dali a few times, to see Zhazha and other friends, but moving there had been impossible with the compromises that a relationship and career involved. Now, following a break-up with my girlfriend and with remote editing work, my fantasy of decamping to Dali was not only possible, but felt natural. A place to hide, to heal, to find something new. I was fleeing to the mountains for the same reasons the reverse migrants did: to escape the city, the rat race, but also the personal tumults that drive us to seek deeper metamorphosis.

There is a myth in China – originating in a fifth-century classical poem – known as ‘Peach Blossom Spring’. In the tale, a fisherman rows up a remote brook into a dense forest. Finding a cave at the stream’s source, he clambers through a tunnel to emerge into a hidden valley. High mountains enclose a secluded garden of blossoming peach trees, with plentiful crops, fresh water and stunning scenery. He is greeted by a village of friendly folk whose ancestors had stumbled upon the valley when escaping the unification of China by its tyrannical first emperor. Here, ‘the old and young are all happy and carefree,’ living in harmony with nature and the flow of the seasons. It is utopia on Earth.

The fisherman stays for a blissful period, then leaves. Despite warnings that it is to no avail, he marks his route out of the valley and on his return to civilisation tells others of its existence. But try as they might, sending out expeditions to locate the valley, nobody is able to find Peach Blossom Spring again.

This escapist tale held particular appeal at the time of its writing, during the turbulent end of the Eastern Jin dynasty. After writing it, the poet, Tao Yuanming, gave up his own post in the civil service to disappear into the mountains, explaining: ‘Birds in a cage long for wooded hills / Fish in a pond yearn for flowing rills.’ In his vision of paradise, Tao noted that there was no official bureaucracy or political strife. His fable of a contemplative life close to nature entered the Chinese consciousness, in much the same way that the myth of Shangri-la has in the West.

Shangri-la, indeed, is a retelling of the same mythos through an Orientalist prism. In James Hilton’s bestselling 1933 novel Lost Horizon, which coined the term, it is three Brits and an American who crash-land in a Tibetan mountainscape, after their plane is hijacked while fleeing war-torn Afghanistan. Taken in by a nearby lamasery, they find themselves in the temperate ‘Valley of the Blue Moon’, cut off from the rest of civilisation, where ageing is halted and there is no war or crime. What’s more, there are distinctly European mod-cons: central heating, a library of English classics and a grand piano, all run by a 250-year-old French Catholic monk. As in its Chinese counterpart, the protagonist – British diplomat Hugh Conway – eventually leaves Shangri-la, never to find it again. Both stories seem to acknowledge that Earthly paradise is unattainable, a reverie.

Nowadays, the stories of Shangri-la and Peach Blossom Spring conjure wider fantasies than just a hidden locale. They stand in for all our hopes and dreams of the life we want to live, the person we want to be.

Alec Ash’s first year in Dali in The Mountains Are High, Scribe UK, £16.99