In this edited extract from Antarctica: A History in 100 Objects we showcase six items that chart the course of human intervention on the most inhospitable continent

By Jean de Pomereu and Daniella McCahey

World Map

Millennia before it was first discovered, the idea of Antarctica resulted in a whole variety of imaginary projections and interpretations. Its imaginary mapping can be traced as far back as the 5th century BCE, when the Greek philosopher Parmenides divided the world into five parallel zones, believing that a southern land mass must exist to counterbalance the known lands of the north. This idea was retained by Aristotle in his Meteorology of c.330 BCE.

With the Renaissance and the emergence of maritime exploration, maps became essential instruments for scholasticism, geographic expansion and trade. A new cartographic tool was introduced during this period – the globe – and in 1531, the French cartographer and mathematician Oronce Fine produced a groundbreaking bi-cordiform world map, in which he represented Antarctica as a massive, solid and largely empty landmass extending across the lower latitudes and the South Pole.

Fine’s map inspired France’s Dieppe school of cartography, the Brabantian cartographer Abraham Ortelius and the Flemish cartographer and engraver Gerardus Mercator, who in his mappa mundi of 1569 also represented a vast and solid Terra Australis, engulfing what we now know as Australia.

Among those who perpetuated Mercator’s projection was the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, who produced the first Chinese world maps with collaborators such as the engraver Li Zhizao. The oldest is the 1584 Yudi Shanhai Quantu, followed in 1602 by the woodblock-printed Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, commissioned by the Wanli Emperor. Hugely significant in its combination of European and Chinese geographic knowledge at the time, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu places China near the centre of the world and features Mercator’s Terra Australis. Slightly later, hand-drawn manuscript versions such as this one populate Terra Australis with both real and imaginary creatures – elephants, crocodiles, rhinoceros, lions, ostriches and dragons, as well as sea creatures and ships along its coastline.

Harness

Few objects are more emblematic of the glories and horrors of the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration than the harnesses used by explorers to man-haul their heavily loaded sledges. This particular harness was designed by Robert Falcon Scott for his Discovery expedition of 1901–04, the first to journey deep into Antarctica’s hinterland.

Scott was confident of the advantages that his new harness design would bring to their endeavours. Once in the field, however, man-hauling still proved torturous. Sledges were often overloaded with equipment and provisions, weighing up to 170 kilograms per man. Some days, the snow surface was so soft and sticky that despite the help received from sails fixed to the sledges, harnesses dug into the explorer’s flesh and bones with every step. On such days, the distance travelled shrunk from 25 kilometres on a good day to just a couple of kilometres. In Scott’s words: ‘The sledge was like a log; two of us could scarcely move it, and therefore throughout the long hours we could none of us relax our efforts for a single moment — we were forced to keep a continuous strain on our harness with a tension that kept our ropes rigid and made conversation quite impossible … it is rather too much when the strain on the harness is so great, and we are becoming gaunt shadows of our former selves.’

A brown textile man-hauling harness used during the British National Antarctic Discovery Expedition, 1901–04

One situation where harnesses were welcome, however, was when someone fell into a crevasse, as happened to Scott himself: ‘I felt a violent blow on my right thigh, and all the breath seemed to be shaken out of my body. Instinctively I thrust out my elbows and knees, and then saw that I was some little way down a crevasse … my harness had held.’ This time, Scott’s harness saved his life, but a decade later the strain and hardship of man-hauling to the South Pole would contribute to his demise and that of his companions.

Polar Star

By the early 1930s, the South Pole had been reached by Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott, and flown over by Richard Byrd. Despite Shackleton’s efforts with the Endurance, crossing Antarctica remained the next big prize in the continent’s exploration, with flight considered the most viable method.

The son of a Chicago coal magnate, Lincoln Ellsworth set his sights on crossing Antarctica. He persuaded Hubert Wilkins, a pioneer of Antarctic aerial exploration in the late 1920s, to serve as his adviser, and commissioned a special, two-seat ski-equipped Northrop Gamma, which could fly at 350km/h, land on ice, and be strapped down in case of storms in the field.

After two failed attempts at crossing the continent, Ellsworth invited Herbert Hollick-Kenyon, a Canadian First World War veteran experienced in flying Arctic rescue missions, to come on board as his pilot. The Polar Star took off from Dundee Island at the northern tip of the peninsula on 23 November 1935. The destination was Little America, an abandoned station first established by Richard Byrd in 1928. Little America was located 3,800 kilometres away on the coastline of the Ross Sea. Reaching it required flying over thousands of kilometres of unexplored territory. In Ellsworth’s own words: ‘We were the first intruding mortals in this age-old region, and looking down on the mighty peaks, I thought of eternity and man’s insignificance.’

Ellsworth and Hollick-Kenyon encountered several dangerous setbacks during their journey. After 14 hours, they made the first of four landings, crumbling the fuselage of their aircraft and destroying their radio. Despite this, they managed to take off again the next day, but a storm forced them to land once again and take shelter for three days. Weather conditions forced them to land twice more before they ran out of fuel and made their final landing, 40 kilometres short of Little America. They completed their crossing on foot, reaching Little America on 15 December 1935.

Kharkovchanka

Of all the motor vehicles that have been tested in Antarctica, the Soviet-designed Kharkovchankas are among the most remarkable. Not only did they transport heavy loads and passengers across the continent, but they also contained 28 square metres of tight but comfortable living and working accommodation for up to eight men.

Weighing 32 tonnes, the Kharkovchankas were completely self-contained, allowing engineers to work on the engine and scientists to carry out their research from the sheltered interior. Rarely driven faster than 10km/h their huge weight meant they burned more than 10 litres of fuel per kilometre.

Two Kharkovchankas were delivered to Antarctica in 1959. Shortly thereafter, the vehicles undertook an 89-day, 5,4000-kilometre return journey from the coastal Mirny Station to Vostok Station and on to the Geographic South Pole, where they surprised United States’ personnel living at the newly established South Pole station. They were greeted with open arms and stayed at the pole for three days, during which the American and Soviet flags flew side by side. Improved versions of the Kharkovchanka continued to be utilised well into the 2000s and some remain on the continent today as historic monuments.

While Kharkovchankas were the first habitable Antarctic vehicles to prove successful in the field, the idea for such machines originated with the United States’ Antarctic Snow Cruiser, a 17 metre-long, 6 metre-wide behemoth that moved on huge rubber wheels rather than tracks. Manufactured in Chicago in 1939–41, the Snow Cruiser proved a public sensation. Once in Antarctica, however, its smooth tyres proved incapable of gaining traction on the snow and it had to be abandoned.

Aquatic Rover

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first satellite, igniting the space race with the United States. For most of this period, the extreme environments of the Antarctic, as well as its status as an international commons for scientific research, turned the region into an analogue for outer space.

Starting in the 1960s, research into extremophiles living on the hostile Antarctic continent, particularly in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, helped to reveal what life might look like on other planets. In the 1970s, microbiologists Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann and Imre Friedmann travelled to Antarctica’s Darwin Mountains, where they discovered unicellular blue-green algae living inside the rocks that tolerated the cold and, in the summer, would rehydrate and photosynthesise. This research suggested that endolithic life forms could survive in Martian environments and could ultimately be used to terraform Mars. NASA later referred to their work when the Viking 1 spacecraft landed on the planet in 1976 and undertook biological experiments to find evidence of life on Mars.

Antarctica is frequently used to develop preliminary research on the equipment and protocols that will one day be used in extraterrestrial exploration. In 2011, scientists and engineers travelled to Marambio Island, along the Antarctic Peninsula, to test a newly developed pressurisable North Dakota eXperimental-1 spacesuit, developed for possible future human field operations on Mars. In 2019, the Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration, developed at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to explore the frozen oceans on Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, was tested at Australia’s Casey Station.

Antarctica also serves as a key site for studying human behaviours and capabilities in extraterrestrial environments. At the Concordia Station, the European Space Agency annually sponsors medical doctors to carry out studies on the effects of isolated, confined and extreme environments on humans.

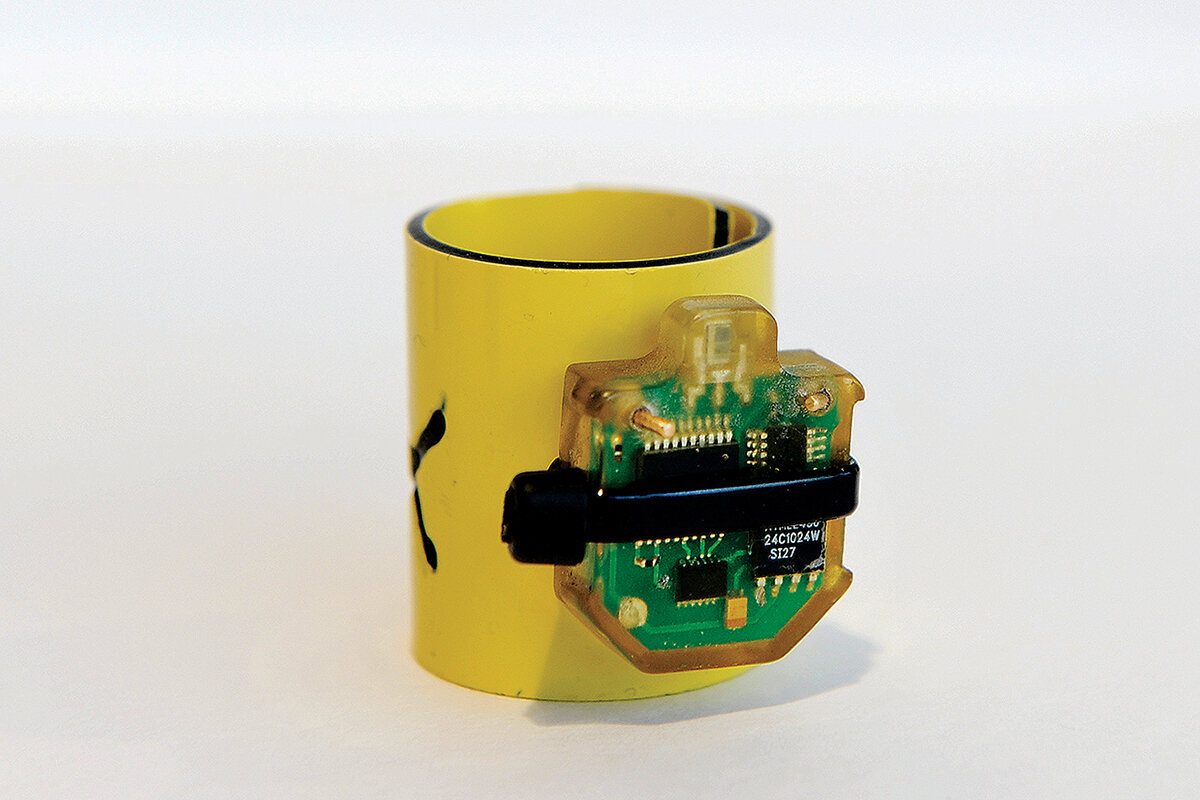

Geolocator

For the French poet Charles Baudelaire, the albatross was ‘the prince of the clouds’, the most legendary of all seabirds.

Eighteen of the more than 22 recognised species of albatrosses live in the Southern Ocean. The biggest is the wandering albatross. With a wingspan that can exceed 3 metres, it can live more than 60 years and fly up to 1,000 kilometres in a single day. Like most species of albatrosses, it spends the majority of its life at sea, only landing on remote outcrops of the Southern Ocean during the breeding season.

Today, albatrosses are under threat, with some species on the verge of extinction as a consequence of incidental mortality (bycatch) in fisheries, invasive alien species at colonies and disease. Their brutal decline in numbers is made worse by their slow reproductive rate, taking up to ten years or more to reach sexual maturity, with some species, including the wandering albatross, breeding only every other year.

The tagging of albatrosses with geolocators was pioneered in the late 1990s and early 2000s. These tiny devices record ambient light and make it possible to estimate a bird’s location twice per day by applying astronomical algorithms to the timing of sunset and sunrise. This allows scientists to measure the scale to which albatrosses have been affected by human activities, particularly fishing, as well as to better understand their habitat preferences and how climate change influences their distributions, year-round.

Despite deep-rooted maritime superstitions about a curse that befalls those who kill an albatross, their killing is nothing new. As early as the second voyage of James Cook, when he ventured south of the Antarctic Circle, the expedition’s naturalist, Georg Forster, ‘shot some albatrosses and other birds, on which we feasted the next day, and found them exceedingly good’. Cook’s account of this voyage possibly also inspired the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge to write The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, published in 1798 and arguably the first piece of Antarctic literature. In this poem, Coleridge recounts the story of a sailor needlessly killing an albatross with his crossbow as it appeared out of the fog. As punishment by his crew, the sailor is forced to wear the body of the albatross around his neck and do penance after the souls of the rest of the crew have themselves been claimed by death. For some, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner has become an allegory for the destruction that humans have brought to Polar Regions.