Fungal infections are a growing threat to human health, but they pose an even greater risk to wildlife, particularly amphibians

A deadly fungus that has driven more species to extinction than any other pathogen has spread across Africa unnoticed. Chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd for short, is a highly infectious fungus that affects frogs, toads, salamanders and other amphibians. While other diseases have also damaged animal populations – white-nose syndrome, caused by the European fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, has killed more than 5.7 million bats across North America – none have had the devastating impact of Bd. It’s thought that the fungus has caused the decline of at least 501 amphibian species globally, and has played a role in 90 extinctions. A study by researchers at James Cook University in Australia, described it as ‘the most spectacular loss of vertebrate biodiversity due to disease in recorded history’.

Until now, only African species seemed to have been spared, but new research reveals that Bd is now firmly established throughout the continent. ‘We show that Bd has become more prevalent and widespread across the continent of Africa since the year 2000,’ says Vance Vredenburg, a biology professor at San Francisco State University. ‘This rapid surge may signal that disease-driven declines and extinctions of amphibians may already be occurring in Africa without anyone knowing about it.’

For their study, Vredenburg and his colleagues searched for signs of the fungus in more than 16,900 amphibians, collecting data from thousands of museum specimens collected from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Tanzania and Uganda, as well as skin swabs from live amphibians caught in Burundi, Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They found that while the fungus was present in less than five per cent of the samples collected since the 1960s, its presence suddenly soared to 17.2 per cent in 2000.

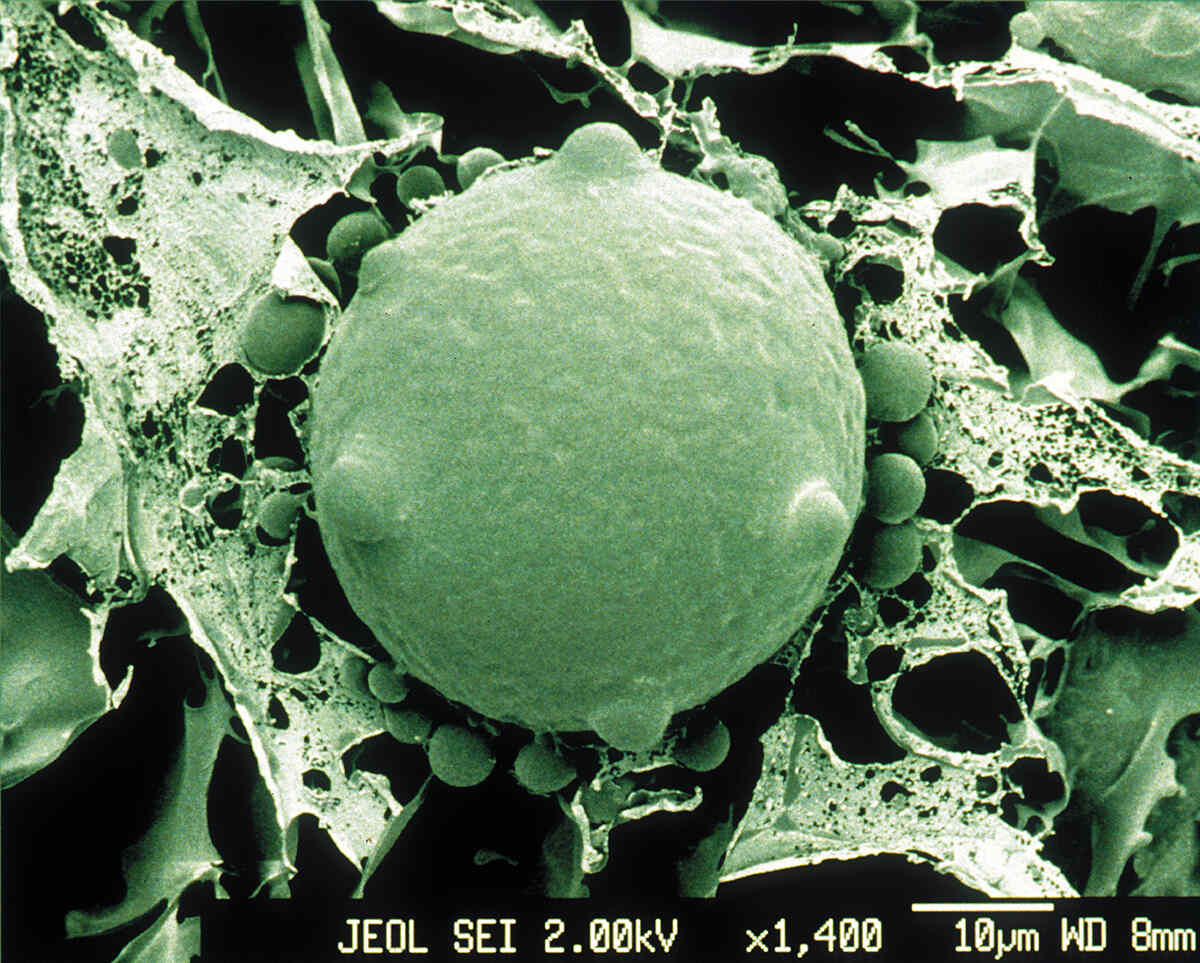

Bd likely existed in some amphibian populations for decades before human activity, most likely human and cargo air travel and the wildlife trade, spread the fungus around the world. It’s so deadly because it attacks the outer layers of the amphibians’ skin. ‘When amphibian skin starts to change thickness, it basically creates a condition where they can’t maintain their internal processes and they die,’ says Eliseo Parra, who worked on the research. ‘If infecting a mammal, it might affect your fingernails or something you wouldn’t even notice, but frogs and salamanders use their skin to breathe. It’s a very critical part of their body.’ The devastation it causes isn’t limited to amphibians; it can affect whole ecosystems of species that eat or are eaten by them.

Climate-change-induced stress could also be making amphibians more susceptible to pathogens, suggests Vredenburg, or it could be making the environment more hospitable for fungi, causing them to spread to new areas. Warming temperatures also mean that fungi must adapt. There’s some evidence to suggest that this is already happening, and it’s not good news for humans. The rapid spread of a deadly drug-resistant fungus called Candida auris in US hospitals and nursing homes could, some researchers suggest, be due to its ability to grow at warmer temperatures – which is unusual for fungi.

‘Emerging from the shadows of the bacterial antimicrobial resistance pandemic, fungal infections are growing, and are ever more resistant to treatments, becoming a public health concern worldwide,’ said Hanan Balkhy, the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) assistant director-general, in October 2022. At the time, the WHO had just published a report highlighting the first-ever list of priority fungal pathogens – the 19 fungi that represent the greatest threat to public health.

The majority of fungal infections in humans typically start through inhalation of spores that are naturally found in the environment – in the soil or on trees; some are even associated with animals. ‘It’s very, very difficult to use prevention as a cure for fungal infections because they’re environmental,’ says Rebecca Drummond, a fungal immunologist at the University of Birmingham. ‘They’re just everywhere. Some of these fungi are actually growing on our skin. They grow in our guts. How do you prevent somebody from being exposed to that?’

For most people, those spores are destroyed in the lungs without them ever even knowing they’ve inhaled them. ‘It’s actually quite rare for a fungal infection to affect what we call an immuno-competent person,’ says Drummond. For people whose immune system is unable to fight off infections effectively, however, those spores can start to germinate and proliferate in the lungs and cause an infection. ‘I tend to think of fungal infections as diseases of the diseased. Most people who get them are usually quite ill already.’

However, Drummond agrees that the development of vaccines and new antifungal drugs, greater access to drugs, as well as increased education and training for medical students, would put us in a much safer position, particularly as the increase in drug-resistant fungi is putting more and more vulnerable people at risk. Vigilance is crucial. ‘In order to treat a fungal infection effectively, you have to diagnose it very quickly,’ she says. ‘Our diagnostics can be a little bit behind that of other infectious diseases.’