Rolex Award Laureate Krithi Karanth’s simple solution for mitigating human-wildlife conflict in India has helped 7,000 families so far

Human-wildlife conflict is on the rise in India. Every year, the Indian government hands out over US$5 million in compensation to farmers and villagers for wildlife damage, but conservationist Krithi Karanth believes that the number of individuals who successfully receive compensation may only represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of the true number of cases.

Karanth has been researching human-wildlife conflict in India for more than 10 years. The daughter of a biological scientist and conservationist, she has a life-long passion for protecting wildlife, and it came as a surprise when she first discovered that not everyone feels the same way. In a country soon to become the most populous in the world, where only a tiny fraction of the terrain is reserved for wildlife, the close proximity between people and wild animals has resulted in the loss of lives, livestock and crops. ‘The fact is, if you want people living next to wildlife, coexisting with animals, you have to help solve the problems,’ she says.

Compensation can help, but Karanth says that the government lacks the resources to process claims quickly, leading to delayed payments and frustration among communities who would take matters into their own hands, often killing animals seen as a threat. ‘Compensation doesn’t solve everything, but it does help these really poor families, who only make about $1,200 per year,’ says Karanth. ‘Any time there’s a crop raiding incident by elephants, they end up losing half their annual income, and it becomes very difficult for them to survive.’

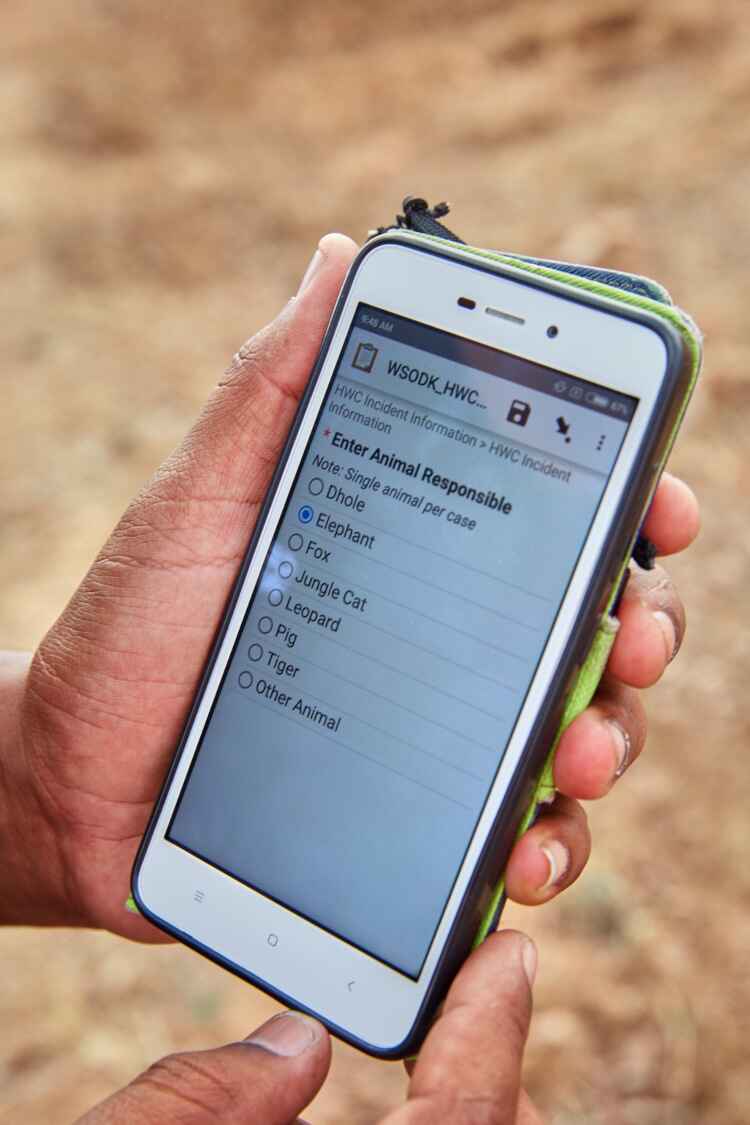

Karanth recognised the importance of being able to respond as quickly as possible whenever something like this happens, ensuring that the system doesn’t fail the country’s most vulnerable. In 2015, she established a toll-free number for villagers to call for assistance in filing for compensation when they suffer losses. The initiative, known as Wild Seve, is currently used by half a million people living in 600 villages near Bandipur and Nagarahole parks in the state of Karnataka.

As of November 2022, the Wild Seve programme has assisted farmers and their families in filing compensation claims for 21,442 incidents of human-wildlife conflict on behalf of about 9,698 individuals and families. Most of the incidences – 94 per cent – involved elephants. It’s estimated that families have received approximately INR 6,86,08,683 (US $973,768) thanks to Wild Seve, who have also built 89 predator-proof livestock sheds.

Evidence suggests it’s an approach that’s working. ‘We have helped whether people have called us once or as much as 70 times, so we have built up a sense of trust over the last seven years,’ says Karanth. ‘And although retaliation against animals does still happen, the number of incidences is very low.’ Karanth and her team currently work in four parks in India, supporting 1500 villages. The plan is to expand this to 12 parks in the next five years. ‘We’re looking to go where there are really high levels of conflict, particularly involving elephants, leopards and tigers,’ she says.

Karanth’s work won her the recognition of being named a laureate of the Rolex Awards for Enterprise in 2019. The award has helped to fund both Wild Seve and Wild Shaale, a conservation education programme rolled out in 500 schools in high-conflict areas, designed to create long-term tolerance and awareness about local wildlife. ‘We use art, storytelling and games to get kids excited about wildlife, and also to teach them the do’s and don’ts in case they ever find themselves in a conflict situation.’ Karanth says that it’s a long-term solution, but that if they can get kids excited about animals, and help them understand the need to share spaces with them, it’s an appreciation that they will carry with them into adulthood. ‘That way, if they are faced with a situation as an adult, their reaction will be more thoughtful, rather than angry.’

According to Karanth, the support of the Rolex Awards has also helped Wild Seve to gain international recognition, and to raise awareness that the work she is doing is not an ‘India-specific thing’, but an initiative that can be adapted and applied to other parts of the world. ‘The idea is that when there are large animals that are prone to conflict with people, you create solutions and response systems that kick in quickly. That goes for anywhere in the world where people live next to wildlife.’