Bryony Cottam meets a doctor dedicated to combating malaria and other deadly diseases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The first time Dr Junior Mudji saw a patient with mpox was in 2016. ‘I knew then that it would become a problem,’ he says solemnly of the disease that, following a multi-country outbreak in 2022, has now claimed more than 600 lives in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) alone.

As chief of research at Vanga Hospital, a 500-bed medical and teaching facility in a rural province of western DRC, Mudji oversees the most complex medical cases in the region. A family physician and global healthcare leadership student at the Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, the Congolese researcher is committed to improving public health challenges, particularly those related to infectious diseases.

His work has helped to advance medical understanding of human African trypanosomiasis – sleeping sickness – a neglected tropical disease that, if left untreated, has a mortality rate of 100 per cent.

Our related medical reads…

Many people opt to travel hundreds of kilometres to the jungle hospital in Vanga, which, despite being understaffed and underfunded, has earned a reputation for healthcare. So when one of his patients died from an easily treatable disease in 2017, Mudji was furious.

Twins Anick and Destin Mukhena were born many hours from a hospital in a village called Musobo, also in western DRC. According to Mudji, most Congolese people couldn’t pinpoint Musobo on a map; it’s that remote. Their mother, Claudine, received only the most basic pre-natal checkups and the pregnancy appeared to be progressing with no complications. Unbeknown to her, however, the twins were conjoined at the navel.

Remarkably, Claudine gave birth to the twins naturally (conjoined births usually require delivery by caesarean section), but without life-saving surgery to separate them, Anick and Destin had just a five per cent chance of survival. Recognising the urgent need for specialised care, Claudine and her husband, Zaiko, squeezed the entire family onto a single motorbike for the difficult, 15-hour journey down the rough dirt road to Vanga.

With no means to conduct such complicated surgery, Mudji arranged for the separation to take place at Kinshasa Hospital, more than 550 kilometres away. He contacted Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF), a non-profit airline that supports remote communities in countries across Africa, South Asia and South America, which flew the family directly to the capital. The 14-hour operation, the first of its kind in DRC, was a success.

In 2023, as DRC was still struggling with the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic – which has compounded the country’s existing healthcare crisis – Mudji’s team tracked down his former patients to check on their wellbeing.

Sadly, they discovered that Destin had died before her and her sister’s first birthday. In the months following the operation, the twins had both contracted malaria. ‘Other mothers in our village have lost their children to malaria, but no-one taught us about it or how to stop it happening,’ says Claudine.

The couple turned to traditional medicine to manage the twins’ fevers, but while Anick responded well, Destin refused to feed. ‘She died in my arms.’

Malaria is the leading cause of death in DRC, accounting for 19 per cent of deaths in children under five years old. It’s the biggest issue facing the staff at Vanga Hospital, where many of the beds are taken by malaria patients, 80 per cent of whom are under five.

Most patients make a full recovery if diagnosed and treated early. The problem, explains Mudji, is that families often arrive at the hospital too late. ‘In the DRC, you have to pay for your care and treatment out of your own pocket, but most of our population can’t afford it.’ Sometimes, they turn to alternative medicine first, ‘but when they don’t get treated, uncomplicated malaria develops into severe malaria. Children with severe malaria are comatose; they can’t eat or talk.’ He says that he sees young patients like this every day.

Globally, in 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the number of malaria cases at 263 million – an increase of 11 million cases from the previous year. Ninety-four per cent of all cases were recorded in Africa, and 13 per cent were in DRC, where, like many of the countries that carry the heaviest burden of malaria, cases are on the rise.

A combination of a tropical climate, deforestation and seasonal rainfall, which creates abundant breeding grounds for mosquitoes, puts nearly the entire country’s population at risk throughout the year, with pregnant women and children at the highest risk of developing severe malaria.

At Vanga Hospital, too, the caseload is increasing. The facility is supported by donations from MAF, allowing local residents to gain access to life-saving treatment for free – while it’s available. As a result, patients travel in from outside the region, placing additional strain on the already-limited resources. ‘Malaria cases are increasing at the hospital because people have heard that if they go to Vanga, they know that we have the right treatment,’ says Mudji.

‘Even though they don’t have any money, they know that we will treat them for free.’ But with so many cases coming in, and the hospital’s isolated location making it difficult to deliver supplies, many of the medicines needed simply aren’t available. ‘The beds are full,’ says Mudji, ‘but our shelves are empty.’

Each morning, Mudji completes his rounds of the hospital’s most critical patients. He lives on-site, working a 50-hour week alongside 14 other doctors. The hospital is built to be staffed by many more. ‘The majority of doctors in DRC want to work in the city, where they enjoy a better life and a higher salary,’ he says. Vanga’s isolation makes recruiting and retaining staff a challenge, and only the most dedicated stay.

Mudji was himself born at Vanga Hospital. The son of a local primary school director, he grew up seeing the impact of infectious diseases on rural communities, many of which rely on subsistence farming. He lost school friends to malaria. He’s sceptical of attempts to globally eradicate the disease – ‘it’ll never happen in DRC’ – but believes a greater focus on health education and better healthcare access for rural populations would drive the number of cases down. ‘Malaria is a well-known disease, which we know how to prevent,’ he says.

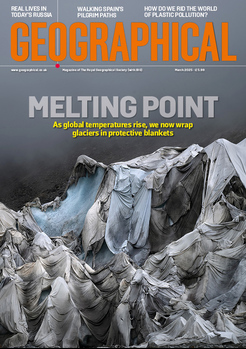

Vanga Evangelical Hospital, western DRC, receives around 60 malaria patients every month. Eighty per cent of cases are children under the age of five. Image: Candice Lassey/MAF

‘With the right treatment, some countries have really reduced malaria, but in the DRC, it’s a very big country, and our challenges are huge.’

In 2023, US$4 billion was invested in the global fight against malaria, less than half of the US$8.3 billion that the WHO considers necessary. International funding has plateaued since 2010, and the gap is growing every year.

Charities such as MAF, which recently raised more than £60,000 to provide Vanga Hospital with thousands of malaria tests and antimalarials, are often the only lifeline for rural communities – but these efforts are paying off. In the two months after drugs were delivered, Mudji and his colleagues reported that not a single one of their patients died from malaria.

While MAF malaria kits have provided short-term relief for the people of Vanga, Mudji admits that a more sustainable solution has to be found. In November last year, a mystery disease struck the southwestern corner of DRC, killing at least 149 people in Kwanga province and afflicting hundreds more with flu-like symptoms of fever, headaches, a cough and anaemia. Most of the cases, which emerged in a matter of weeks, were in children under 14 years old. After reports of the unknown disease sparked alarm, a team of epidemiologists and doctors was sent by the WHO to conduct investigations.

They soon identified the disease as a severe form of malaria that had struck a community already weakened by high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition. The WHO also pointed to ‘low vaccination coverage and very limited access to diagnostics and quality case management’.

Mudji hopes that new malaria vaccines, which have been licensed for use in children, as well as training for new health workers and community outreach, will make an impact.

DRC received the first 693,500 doses of the newly approved R21 vaccine in October, a ‘major milestone in the country’s efforts to safeguard the health and well-being of children’, says DRC WHO representative Boureima Hama Sambo. But in a country the size of Western Europe, most of which has no transport and electrical infrastructure, and with no new sources of funding, there’s still a long road ahead.